UCL-Energy student visits Venice Biennale 2014

11 September 2014

Carrie Behar, PhD student at UCL-Energy, was awarded a travel award by the LoLo CDT to visit people or places of relevance to her work.

I was the lucky recipient of a £500 travel award from the LoLo CDT, which was to be used to visit people or places of relevance to my work. I chose to attend the Venice Architecture Biennale, something which I had wanted to do ever since hearing some of my fellow undergraduate architecture students recounting tales of their adventures, which mostly seemed to involve eating pizza and wading around in wellies, almost a decade ago! Thankfully, during my visit in June this year we were spared the ‘acqua alta’ and were able to enjoy this beautiful city at its driest and sunniest (though perhaps most crowded too).

Figure 1: View of San Giorgio Maggiore

You may, perhaps, be wondering what an exhibition dedicated to showcasing the most avant-garde architecture from around the world has to do with researching ventilation in low energy social housing in the UK? As my PhD research has progressed I have become more and more aware of the role of architecture and architects in shaping the physical environments that we occupy and, subsequently, the impact that this has on the people who then go onto living in or occupying these buildings. I don’t think you can study what people do, or what is often referred to in academic jargon as ‘human behaviour’ without understanding why and how that particular physical and spatial configuration (i.e. the building) came to be the way it is. Furthermore, as I observe the industry from the vantage point of academia I believe that matters of energy efficiency and sustainability are growing in importance in professional practice, yet I wondered to what extent these ideas had reached architectural theory?

The biennale exhibitions are spread out across multiple venues, around what is, thankfully, an extremely walkable city. The curator this year is Rem Koolhaas, an eminent architect, founder of OMA and Professor in Practice of Architecture and Urban Design at Harvard.

Whereas some reviewers have criticised the lack of ‘design’ and architecture in the show, I really welcomed the brave decision to elevate the status of construction elements such as windows, doors and walls to legitimate units of enquiry. It seemed particularly fitting in a city where roads are replaced by canals and a canon and cannonball are used in place of a mullion!

Figure 2: One of Venice’s many canals and Façade of Hotel San Fantin

Another reason I enjoyed the exhibition is that it presents a huge body of research, amassed, I believe, by Koolhauus’ students at Harvard. This kind of obsessive scrutiny of apparently mundane architectural elements, or ‘fundamentals’ is right up my street. I loved the way architecture was presented in an almost archaeological and anthropological manner, rather than a form of ‘high art’ or as the output of individual creative genius, as is so often the case.

The level of detail presented is outstanding; from an analysis of Fanger’s theory of thermal comfort, to a display of historic windows from the Charles Brooking Collection. it all seemed to tie in so nicely with the ideas I’ve been exploring around how material objects form a key element of our everyday habits and routines which are carried by people as ‘social practices’.

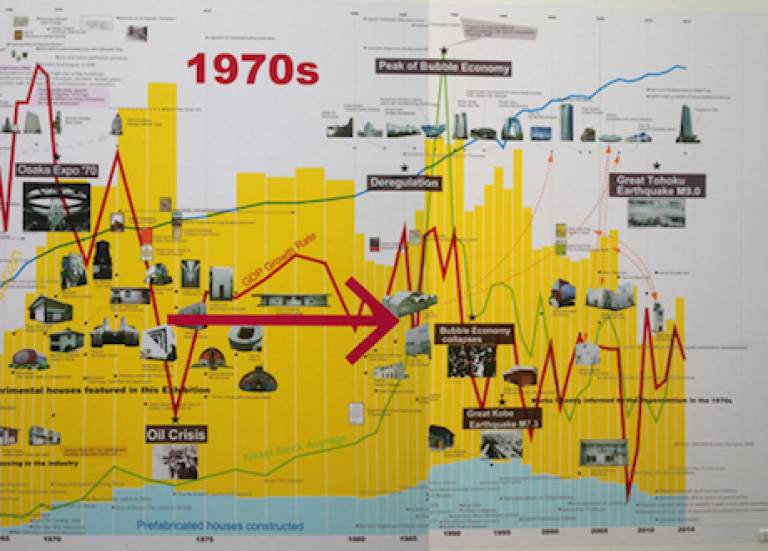

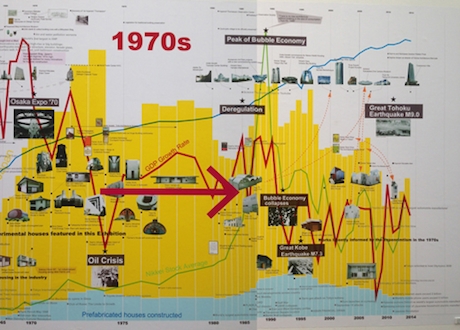

The theme for the exhibition is ‘Absorbing Modernity: 1914-2014’. A review of modernism isn’t necessarily fertile ground for discourse on sustainability and environmental awareness; however I was struck by how many references to the oil shocks of the 1970s made it into the exhibits, such as in the timeline of Japanese housing construction which, in the words of architecture critic Oliver Wainwright, ‘charts the investigations of the generation of architects who were confronted with the precipice of doom after the post-war economic bubble popped in the 1970s, facing the oil crisis, environmental pollution and stagnating living conditions’.

Figure 3: Mural from Japanese Pavilion

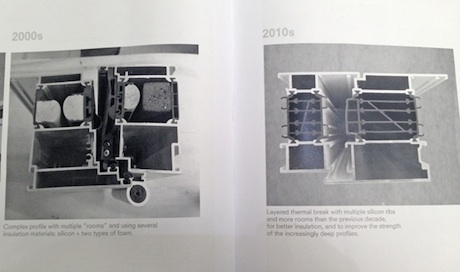

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I particularly enjoyed the room about windows, where the ideas around the function of windows, ranging from visibility to haptic connections with nature to letting in light and (of course) for ventilation, resonate with the findings of my own research. There was a fascinating (albeit niche) section in the accompanying book which traced the evolution of window frame profiles from simple timber structures to complex composite systems incorporating acoustic attenuators and thermal breaks.

Figure 4: Photo of evolving window profiles from accompanying catalogue

Also relevant for those of us with an interest in sustainability were the displays accompanying the elements ‘façade’, ‘toilet’ and ‘fireplace’.

One of the main themes in the ‘Toilet’ room was that the WC that is common around the world is inefficient and needs reinventing for a sustainable future. Although the Roman toilet was good fun, the innovative ‘Blue Diversion’ toilet which separates solid and liquid waste, was definitely the most interesting object in the room.

The relevance of façade design to energy efficiency is evident. However, the ideas around how the different functions of the façade co-evolve with historical, social and cultural events as well as technological advances were meticulously presented here, drawing on diverse references such as Rachel Carson’s seminal ‘Silent Spring’ and photocatalytic wall tiles.

I was impressed to see thermostats feature in the ‘Fireplace’ room, where a flowchart on the wall traced the development of heating systems throughout history. However, the attention grabber in this room was an exhibit titled ‘local warming’ which showed how infrared heating could be activated by tracking people’s motion so that comfort heating is only provided exactly where it’s needed (though I did wonder what happens if you are sitting too still at your desk?!)

Figure 5: Motion tracking infrared heating installation

As well as the main exhibition, 65 countries hosted their own shows in pavilions and spaces scattered around the city. The variety of interpretations of the theme were quite astounding - from a recreation of a mausoleum to Józef Piłsudski in the Polish pavilion to a seductive display of seaside resorts in the Greek pavilion.

Among individual counties’ displays concerns around environmental sustainability were generally less visible, with a few notable exceptions. Malaysia’s exhibition was titled ‘Sufficiency’ and presented a selection of architectural models and conceptual pieces which addressed urban farming, scarcity of resources climate change and catastrophe. The exhibits were a bit hit and miss but at least the sentiment was there. Indonesia contributed a more subtle exploration of ideas relating to sustainability - the exhibition focused on craftsmanship, traditional vernacular architecture and the use of wood and natural materials as a more ethical way of providing thermal comfort. As South East Asia is one of the most vulnerable regions in the world to the effects of climate change it is perhaps understandable that these two countries have drawn on themes of resilience in their displays.

Overall I was surprised and delighted at how enjoyable and thought provoking the show was and, as this is the first year that the Biennale is running for an unprecedented six months, there is still time to pack your bags and go as the exhibition is open until November 23rd!

Close

Close