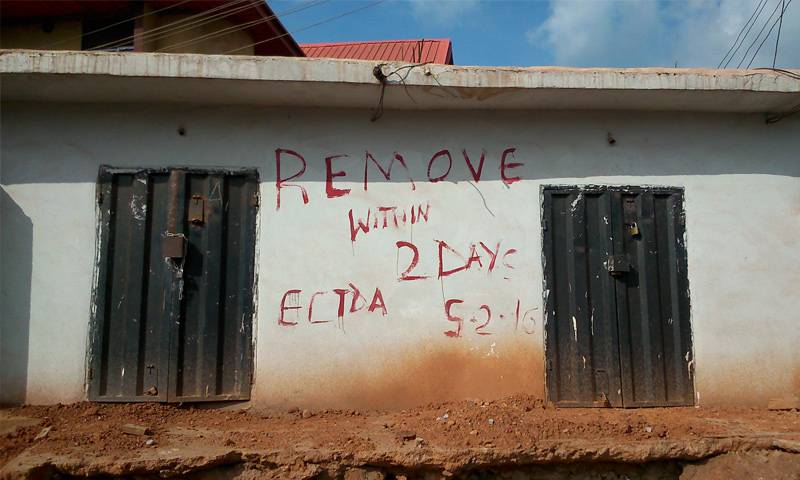

The need for infrastructure in Nigeria is being used as a pretext to displace low-income communities to release urban land value.

Wellbeing, rather than income, is increasingly used as a criterion to measure development outcomes. For Nigeria – a country that has at times seen sustained economic growth, alongside increasing rates of both income poverty and subjective poverty – wellbeing is the aim of a key development policy: Nigerian Vision 20:2020.

For the past four years, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit (DPU) has been coordinating research under the theme ‘Wellbeing of Urban Citizens’ for the Urbanisation Research Nigeria programme, funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID).

In 2014, the DPU’s Dr Andrea Rigon, together with partners from Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, carried out scoping research with strategic stakeholders in five Nigerian cities: Abuja, Kaduna, Zaria, Lagos and Ibadan. The aim was to identify the key issues for urban wellbeing. The findings formed the basis for six further projects covering industrial policy to transport and water poverty.

A key issue that emerged from Rigon’s research was inappropriate planning that serves particular interests and further entrenches inequalities. For the DPU’s Dr Barbara Lipietz and Julian Walker, investigating ‘Urban Infrastructure Projects and Displacement’, this is a key factor underlying the phenomenon of mass displacement in Nigeria. In 2007, the UN HABITAT Advisory Group on Forced Evictions reported that more than 2.3 million people had been evicted from their homes in Nigeria between 1995 and 2005. Lipietz’s and Walker’s research suggests that displacement continues at a similar scale today.

“There is a massive gap between the sophisticated de jure legal due process governing land acquisition for infrastructure ‘in the public interest’ and what happens in practice,” says Lipietz. “What we see, de facto, is a lot of ‘creativity’ in the legitimisation and governance of displacement, and that raises questions about the covert triggers of displacement.”

One important finding from the research is the critical role of information in this process. The opacity of information means that people’s sense of being able to hold on to the land they occupy is constantly threatened. Working with local NGO Spaces for Change and colleagues at Enugu University, Lipietz and Walker have started to develop a national database of evidence covering cases of infrastructure-driven displacement.

This is no easy task – records are episodic and mainly cover large cities, but Lipietz hopes that this database can be maintained and expanded. “As a next step, we aim to work with Spaces for Change to develop a live database of infrastructure-related displacement which can feed into, and help reframe, the public debate about evictions,” she says.

Findings from the six individual DFID-funded projects will be presented in Abuja, Nigeria, in February 2018.

Close

Close