From broadband to genetic sequencing and solar panels, the public sector has always been a nurturer of innovation. It’s time the state’s role as innovator is recognised. Words: Brendan Maton

Everyone in academia knows what a business school is. But what is the equivalent institution for civil servants? This is the question that Professor Mariana Mazzucato hopes to answer by founding the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP) at The Bartlett.

Mazzucato – who joined this year from the internationally renowned Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex, where she held a chair in the Economics of Innovation – is a rarity: a working academic who not only has a media profile and the ear of political leaders, but also one whose arguments are also widely understood (everyone recognises Stephen Hawking but can you summarise his ideas?).

Mazzucato’s The Entrepreneurial State, rated by the Financial Times as one of 2013’s books of the year, overturned the myth of the “sluggish state”, by showing that some of the greatest innovations in capitalism trace their funding back to the state. Her goal is that the IIPP becomes an institution that can learn the lessons of bold and mission-oriented state agencies – how to organise themselves internally and how to work on new missions with other types of actors.

According to Mazzucato, the state is far more entrepreneurial than people understand. If organised in strategic ways, it has had, and can have, the deep pockets and patience to fund frontier research and invention – but rarely gets the praise due for this work.

Among a generation that has grown up to believe in “small government” and the propensity to determine any endeavour’s worth by its monetary value, it is easy to succumb to the narrative that all the best ideas have been dreamed up and implemented by the private sector. (One institution she praises is the BBC, which created the widely used iPlayer, but which, as a public service, received fewer plaudits than YouTube or Spotify).

While the world lionises Apple, Facebook, Google and the tech giants of Silicon Valley, Mazzucato draws the thread of this particular narrative back to the governmental agencies that, at the height of the Cold War, were tasked with keeping the US ahead of Russia in terms of technological prowess.

Organisations such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) – well-funded, autonomous, decentralised and long-termist – fostered the development of microchips, personal computers and early internet technology. Its success encouraged US administrations – well into the Reagan era of small government – to back similar institutions investigating various fields, not just defence, but also new energy, nanotechnology and healthcare.

“By not giving the state its credit, enriched companies have been able to lobby for lower tax and lower regulation rather than contribute more to the public purse they have depended on”

Silicon Valley has done well to market publicly-funded inventions in computers, smartphones and pharmaceuticals. But, as Mazzucato never tires of pointing out, by not giving the state its credit, enriched companies have been able to lobby for lower tax and lower regulation, rather than contribute more to the public purse they have depended on.

And this dynamic also reduces the confidence of state agencies: “There is such a lack of confidence in state leadership on innovation in the UK, for example. The government department responsible has changed its name four times since I started working here!”

However, while she approves of a bolder role for the state, she is not advocating old fashioned dirigisme, and warns that politicians must be kept away from the actual management of innovation organisations. For a real example of Mazzucato’s recommendations on national policy, read her strategy report for Brazil, co-authored with one of her research fellows Caetano Penna (see box, ‘Read the Research’).

This clarifies where Brazil has achieved success, such as in agrichemicals; where it has failed, such as in technology parks that have not transferred research knowledge into production; and how macro-economic strategy interacts with meso-level ecosystems. Which brings us back to the IIPP.

There are plenty of business schools offering to make better CEOs by getting them to think outside narrow frameworks, with concepts such as “rejuvenating the mature corporation”, but what is the equivalent for the public sector?

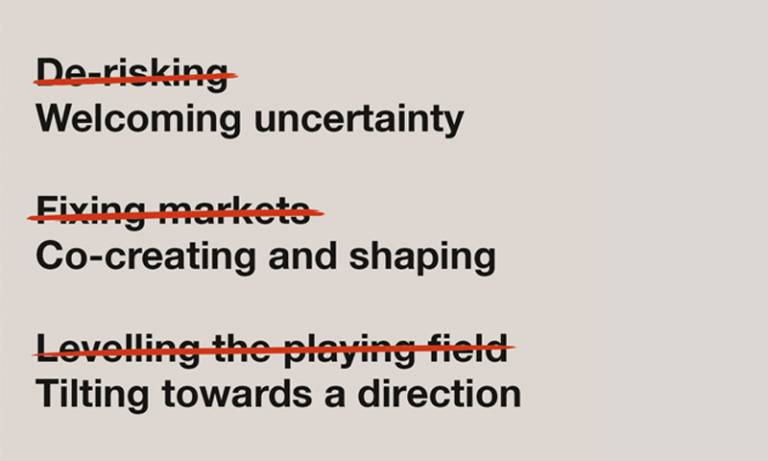

There are already plenty of universities – including UCL – offering a Masters in Public Administration to make better department heads, but none offers the heady cocktail of innovation and public purpose to rethink the notion of public value so that what the public sector does is more than just fix markets, or de-risk “wealth creators”.

Mazzucato’s programme aims to build confidence in the civil service to see themselves as wealth-creating agents too, with the need to be flexible, and to welcome risk-taking, experimentation and learning. Furthermore, as innovation has not only a rate but a direction, the IIPP wants to open up a new debate about how to learn from mission-oriented policies, in order to direct innovation towards modern problems concerning the environment, healthcare and space.

Mazzucato argues that industrial policy should not be focused on sectors but rather on big problems – missions – that multiple sectors need to solve. One of the IIPP’s most exciting projects regards the emerging Low Earth Orbit economy with NASA, possibly the world’s most famous mission-oriented innovation agency. But it is not inventions per se that motivate her.

It is new forms of public-private partnerships that can make sure that missions funded by the public don’t only socialise risks, but also rewards. Her message is a bi-partisan one, appealing not to parties but to common sense about what shape future capitalism should take and how to build symbiotic forms of partnerships that create opportunities for future investment while also fulfilling societal goals.

Given Mazzucato’s own preference to think big, it is no surprise that the first courses available at the IIPP are likely to be for public-sector executives from different types of global public organisations. It is the people with the greatest responsibilities now that she wants to reach. But, as policymakers don’t work alone, the programme will be aimed at creating a new framework for partnerships that will only work if the people in the classroom are also from the private sector and the voluntary sector.

Mazzucato admits that alumni of the IIPP will need to be careful. The paradox of her success is that public agencies tasked with innovation will now be under far more scrutiny from commentators and political paymasters than the likes of DARPA were in the 1960s. “We don’t live in a patient culture,” she says. All the more reason to fight for change.

It’s time to think big

There was a buzz in the air for the IIPP’s sold-out launch on 12 October 2017. Among those in the audience were music producer Brian Eno, artist Cornelia Parker, British Library CEO Roly Keating and venture capitalist Hermann Hauser, all of whom are also part of the IIPPís interdisciplinary Advisory Board.

Mazzucato used the launch to announce one of the IIPP’s most ambitious programmes starting in 2018: the Mission Oriented Innovation Network or MOIN, an idea she and the IIPP’s new Deputy Director, Rainer Kattel, have been planning for some time.

MOIN is a platform for public agencies around the world to learn from each other's experiences of working outside the box of fixing markets, towards a new framework of actively co-shaping and creating markets. And, in the process, creating value.

Mazzucato’s forthcoming book, The Value of Everything, tackles the ‘value question’ head on. It will no doubt raise as many questions as The Entrepreneurial State, making sure that the IIPP remains at the centre of the debate for years to come.

Close

Close