Ha Eun Monica Park (BA History of Art) - Supervisor: Dr. Allison Stielau

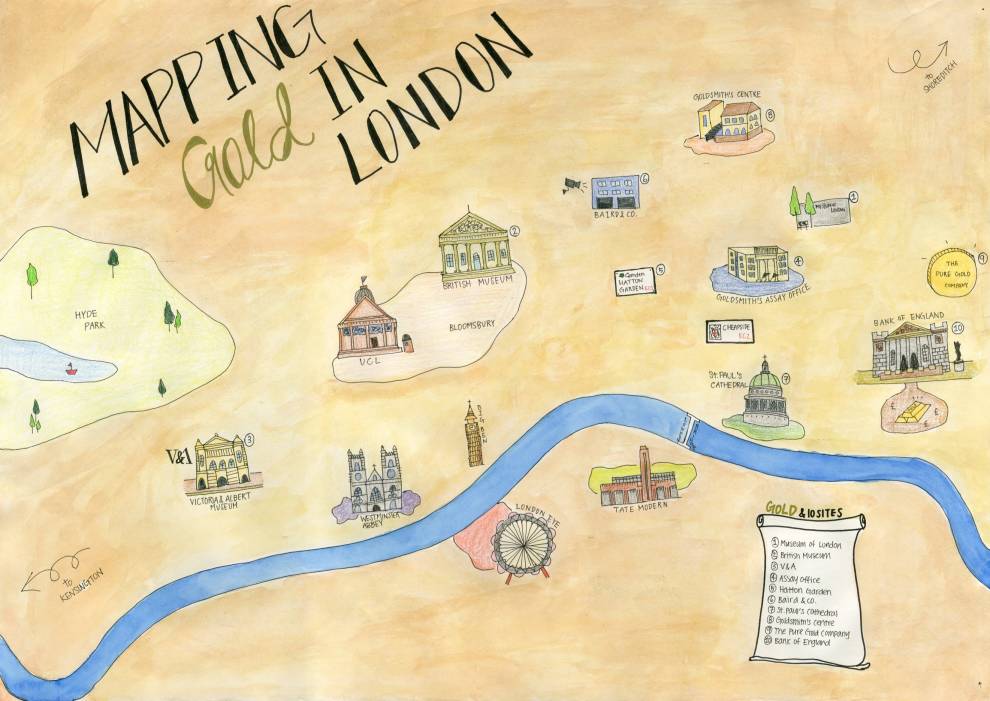

First Year of Research: Mapping Gold in London

Second Year of Research: Gold in Portrait Miniatures of Early Modern England

The aim of the project was to map and investigate sites around London which are linked to the various uses of gold, including jewellery making, painting, fashion, banking, commodity trading etc. In the course of the project, I visited ten sites in London that are associated with gold and precious metals:

Gold as a bridge linking historical and modern-day London

The Museum of London displays extraordinary materials found in the Cheapside Hoard, which was discovered near St. Paul's Cathedral. The Cheapside Hoard archived a hoard of jewelleries mainly from the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, including those made with enamelled settings and gemstones. It preserves gold objects that in other circumstances would have been melted down as fashions changed and owners fell on times of financial need. The Cheapside Hoard offers vivid evidence of London’s active participation in international trade and gold manufacturing throughout history. Its value consists not only in the precious materials it contains, but also this connection to the historical past.

2. British Museum

Gold in various cultural contexts

The British Museum presents the use of gold in a variety of cultural contexts. In pre-modern times, gold was mined and often used in exchange for industrial resources, such as copper, tin and brass. During the pre-Hispanic period in Columbia, gold was not regarded as currency but used as a way to publicly assert one’s socio-economic status in his or her attire. In Egypt, thin gold sheets were applied to the surface of the mummy cases to show respect for and to commemorate the deceased.

Gold in fashion

The V&A offers examples of gold employed in the arena of fashion. The Mantua, for example, was an article of women’s clothing popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Instead of having a separate bodice and skirt, a single length of fabric hangs from the shoulders to the floor. The image below demonstrates how silver and gilt thread could be used on the silk and linen surface of the cloth to produce glittering effects. The use of gold in fashion has continued to develop over time. Instead of actual gold, many designers favour artificial gold fabrics for decoration. They are able to imitate the concept and materiality of gold with its shiny and reflective surface. The use of gold in fashion underscores the breadth and flexibility of its application, as well as its potential to signify even when the pure metal is not present.

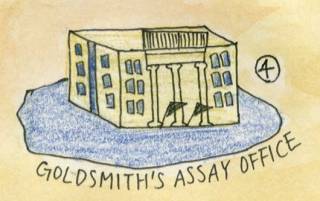

Gold in a regulatory system

The Goldsmiths’ Company was first established in the twelfth century to regulate crafts and trades of the goldsmiths and to officially inspect the hallmarking system. In fact, the word ‘hallmarking’ originates from the fact that the precious metals inspection took place in Goldsmiths’ Hall. The London Assay Office, part of the Goldsmiths’ Company, continues to regulate gold and other precious metals. The Assay Office not only plays an important role in precious metal inspection and minted coinage regulation, but also greatly contributes to the trade market of gold in England by establishing a reliable assay and hallmarking system. The images below present parts of the precious metal inspection processes that take place at the Goldsmiths’ Company Assay Office.

Gold and jewellery trades

The active circulation of gold in England since the medieval period has sustained the jewellery making business for centuries. A major site of this trade has long been London’s Hatton Garden, which continues to draw customers. Although there has been a decrease in the number of craftsmen operating in the neighbourhood, a cluster of shops in Hatton Garden still deals in both new products and second-hand jewellery, and thus remains a site for buying and selling. The reliably secure value of gold makes Hatton Garden a draw for customers from as far away as India, South Africa, and China.

Gold in the currency system

Before the introduction of gold bars in England, Baird & Co. started selling gold coins in 1967. The kinds of precious of metals that they usually deal with are gold, silver, platinum, palladium, and rhodium. Customers have the option to buy gold in the form of either bars or coins. The company also produces a variety of bullion products for jewellers and goldsmiths for the creation of high quality artworks or commodities. Gold in this context is usually perceived as a commodity that is directly linked to the concerns of raising profits and commercialization, which is very different from how gold is treated in museums.

7. St Paul's Cathedral

Gold in a sacred space and its symbolic meaning

From the exterior of St. Paul’s Cathedral, one can see a large gilt statue of Saint Paul atop the cross. The sunlight shines directly upon the statue, making it glitter. Inside, gold embroiders the ceiling. When the light comes through the window, surfaces glint. Since ancient times and across a variety of cultural contexts, gold has been used to express reverence towards sacred objects and figures. Because of gold’s rare, shiny and un-corruptive quality, it was particularly embraced in religious architectural settings. Its ability to maintain its materiality reminded people of immortality and divinity. In such contexts, gold had both physical and metaphorical effects. Such perceptions are directly reflected in the architecture of St. Paul’s. Gold in the space was perhaps used to represent immaterial things: all that is abstract and intangible. The glint of gold in streaming sunlight could be one way to show that God is mingling communicating with believers

Gold and goldsmiths

Training and apprenticeship are essential to maintaining the tradition of goldsmiths’ craftsmanship in England. The training at the Goldsmiths’ Centre involves not only the skills needed in making gold objects, but also the inspiration that is necessary for producing superlative pieces. Kyosun Jung, a Korean silver/goldsmith working at the Centre, said in an interview with me, ‘Top craftsmanship with inventive design and functionality: these are fundamental in my work. I find and utilise inspiring research from nature in particular, organic forms and geometry with its infinite creations for patterns and textures.’ She put further emphasis on how important the Centre is for other goldsmiths and silversmiths, including herself, in developing skills and maintaining continuity in precious metal in art businesses.

9. Pure Gold Company

Gold as an investment

Many believe gold makes a good investment because it is scarce, durable, and maintains a high value across time and economic fluctuations. When the future is insecure and there is social, political, and financial instability, the rate of gold investment tends to rise significantly. Central banks and nations hold a certain amount of their wealth in gold to protect themselves from sudden and unexpected financial decline and to maintain national power. The Pure Gold Company provides services for individuals who are seeking to store their wealth in the form of gold. Unlike the gold used in artefacts and architecture, here gold is viewed solely as an investment.

Gold in a bank

The Bank of England is an official custodian of the UK’s gold reserves. The goldsmiths were the first to start organizing the system of lending, deposit, and note issues. During the eighteenth century, gold started to replace silver in the monetary system of the United Kingdom. It automatically led to the firm establishment of a gold standard and gold’s position as universal currency. Despite the introduction of paper money, the currency still maintained an explicit link to gold. Under this system, paper money was convertible on demand into gold. The gold standard established in England was adopted by many countries including France, Germany, Japan, Russia, and the United States. For this reason, beneath the City of London, there is a vault that stores more than five thousand tonnes of gold, which is around 400,000 gold bars. In 1931 Britain dropped the gold standard, along with the US and many other nations, as it can promote inflation by cheapening the value of their own currencies.

Gold in Portrait Miniatures of Early Modern England

As an extension to my work as a Laidlaw Scholar last year, this summer I have been researching Elizabethan portrait miniatures and their use of gold as both a painting material and the subject of representation. After visiting the “Elizabethan Treasures” exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, I was genuinely fascinated by the use of gold in miniatures and how it could have different impact than the conventional large-scale portraits, which were designed to be seen by many.

The question of gold’s symbolic value for the monarchy is particularly important for one miniature I looked at: Nicholas Hilliard’s portrait of Elizabeth the I of around 1600, which is now in the V&A’s collection. Hilliard was trained as a goldsmith and his skills as a metalworker carried over into the representation of the monarch, with her delicately gilded hair and prominent jewellery and crown. The miniature itself is enclosed within a ruby-studded golden locket reminiscent of the queen’s elaborate jewels.

After the summer, I plan to carry on this research into my dissertation for the completion of my single-honours degree in History of Art.

Nicholas Hilliard, Portrait Miniature of Elizabeth I, ca.1600, Portrait in a gold enamelled case set with diamond and ruby, 62mm X 48mm, (London: Victoria and Albert Museum)

Special Thanks to...

- Dr Allison Stielau, Lecturer in Early Modern Art, UCL

- Dr Alison Wright, Head of History of Art Department, UCL

- Robert Brown, Departmental Administrator, History of Art Department, UCL

- Lauren Sperring, Graduate Student and Events Administrator, History of Art Department, UCL

- Martin Perks, Visual Resources Technician and Web Editor, History of Art Department, UCL

- Dr Tabitha Tuckett, Rare Books Librarian, UCL

- Dave Merry, Head of Training, Education and Trading Standards Liaison at the Goldsmiths' Company Assay Office

- Kyosun Jung, Silversmith at the Goldsmith's Centre

- Christopher Cullen, Programme Manager of Laidlaw Research and Leadership Programme, UCL

Bibliography

Campbell, C.J, et al., Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2015)

Cherry, John, Medieval Goldsmiths (London: British Museum Press, 2011)

Forbes, J.S., Hallmark: A History of the London Assay Office (London: Goldsmiths’ Co. Unicorn Press, 1999)

Forsyth, Hazel, London’s Lost Jewels: The Cheapside Hoard (Philip Wilson Publishers, 2013)

Furlong, Gillian, Treasures from UCL (London: University College London Press, 2015)

Lichtenstein, Rachel, Diamond Street: The Hidden World of Hatton Garden (London: Penguin UK, 2012)

Smith, Jeffrey Chipps, The Art of the Goldsmith in Late Fifteenth-Century Germany (Kimbell Art Museum, 2006)

Zorach, Rebecca and Michael W. Phillips Jr, Gold: Nature and Culture (London: Reaktion Books, 2016)

Close

Close