An Interview with Solomon Gebreyes Beyene: The Chronicle of King Śarḍa Dǝngǝl (r. 1563‒1597)

The ITIESE team catches up with Dr Solomon Gebreyes Beyene to talk about his latest project The Chronicle of King Śarḍa Dǝngǝl (r.1563‒1597). Dr Solomon Gebreyes Beyene is a research fellow at the University of Hamburg’s Hiob Ludolf Centre for Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies (HCLEES) who specializes in Geʿez Philology as well as medieval and modern Ethiopian history. His doctoral thesis focused on The Chronicle of King Galāwdewos (1540–1559): A Critical Edition with Annotated Translation (2016) and he has also published articles on various topics including royal historiography, medieval history of Ethiopia, and digital humanities.

Dear Solomon, first of all thank you for agreeing to this interview. To start things off, could you tell us something about yourself and about how you came to work on Ethiopic manuscripts?

I obtained my BA degree in History (2000) and my master’s degree (2007) in History from Addis Ababa University. I worked as a cultural heritage expert at local cultural and tourism office for three years in Ethiopia. I was also a lecturer, teaching various history courses and Civic and ethical education in government universities and private colleges of Ethiopia for eight years, until 2012.

I have always been very interested in medieval history of Ethiopia, and realized that studying Geʿez philology could allow me to learn more about medieval Ethiopian history, as many medieval Ethiopian historical sources from that period are available in this classical language. So, the desire to study historical texts, especially Ethiopian royal chronicles, inspired me. I got a DAAD scholarship to do a PhD in Germany and I decided to go to the renowned Hiob Ludolf Centre for Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies in Hamburg under the supervision of a leading scholar in Ethiopian studies, Professor Dr Alessandro Bausi in 2012. For my PhD I worked on a medieval Ethiopian royal chronicle known as The Chronicle of King Galāwdewos. This work is arguably the most important primary source to study the history of Christian-Muslim relations in the northern Horn of Africa during the turbulent years of the 16th century. After completing my PhD in 2016, I was hired at the same centre as a Research Fellow in the Beta maṣāḥǝft and TraCES projects.

A lot of your research focuses on Ethiopic Chronicles, could you explain to our readers what a chronicle is and talk to us about the history of this particular genre?

Most readers will think that the word “chronicle” refers to daily news reported by journalists. In history, however, the term is associated with records and narratives about the daily activities of kings and their notables. Chronicles may differ in their style, structure, philosophy and content from country to country. However, in most countries, a chronicle is, in a narrow sense, a sort of a panegyrical biography of a king, queen, lord, or pope that glorifies his words and deeds while censuring those of his contenders and enemies. Chronicles may also incorporate legends and facts about the genealogy, upbringing, military success, piety and statesmanship of their protagonist. Chronicles are often one of the few sources of written information about the history of a country or people.

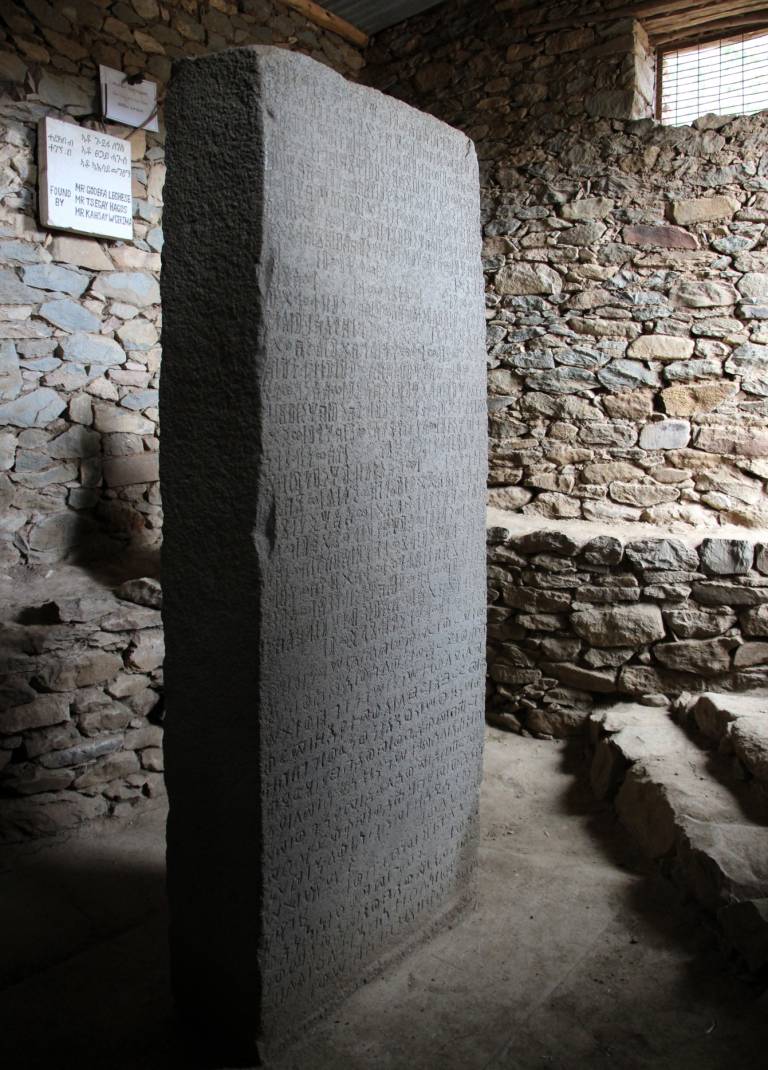

Ethiopia has a long history of chronicle production. The earliest examples date to beginning in the 14th century and chronicles were written for nearly every ruler until the beginning of the 20th century. While we have no evidence of the production of chronicles before the 14th century, in late antiquity some of the Aksumite kings recorded their campaigns and victories on inscription (Fig. 1). As far as we know, chronicles were not produced for member of the Zāgʷe dynasty (ca. 11th cent. to 1270 CE), so, as a genre, chronicle production in Ethiopia may have started with the rise of the Solomonic dynasty in the late 13th century.

Fig. 1. A monumental trilingual inscription by the Aksumite King Ezana (r. ca. 330–65/70[?]) in Aksum (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Ethiopian royal chronicles were written in Geʿez (classical Ethiopic) till the second half of the 19th century as well as in Amharic from this period onwards. Most were written during the king's lifetime by a chronicler who accompanied the king on his campaigns or took part in the important activities of court life. The first chronicle was written in the 14th century for King ʿAmda Ṣǝyon. Other important examples include, the chronicle of a powerful 15th century Emperor called Zarʾa Yāʿqob (which was written in the early 16th century) and the chronicle of King Galāwdewos (composed two years after the death of the king, in 1561). Also noteworthy, is the Chronicle of Śarḍa Dǝngǝl (r. 1563‒1597) which describes the expansion of the Christian kingdom and a confrontation with the Oromo people. This work also discusses some inter-religious war between Christians and the “Falasha” – a local minority Judaic communities (now more appropriately designated as Beta ʾEsraʾel).

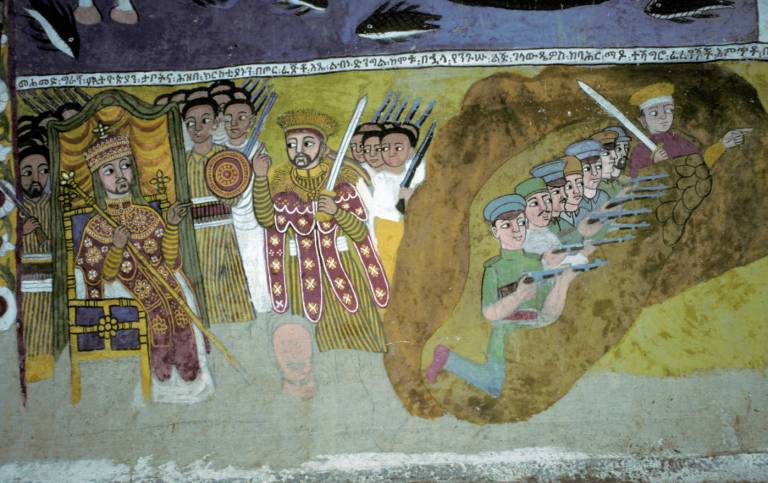

Perhaps the most voluminous of all Ethiopian chronicles is that devoted to the activities of King Susǝnyos (r. 1607‒1632). Many Gondarian kings, who reigned from 17th to 18th centuries, also had a chronicle composed for them (Fig. 2). Finally, in more recent times, chronicles were also composed in Amharic for Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–68) and Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913). All these royal chronicles have been edited and translated into various European languages since the last quarter of the 19th century. However, new editions and translations into English are crucial to make these historically useful works accessible to a wider readership.

Fig. 2. The death of Gondarine emperor Iyasu I (r. 1682–1706) from a 19th century Ethiopian manuscript in Tigray (Photo: Michael Gervers, courtesy of the DEEDS project).

In 2019 you published a critical edition and translation of The Chronicle of King Galāwdewos (1540-1559). What led to work on this particular text?

Well, as I have pointed in the above, it is important to re-edit royal chronicles employing all the known manuscripts witnesses, translating them into English accompanied with new annotation. With this aim in mind, I selected the neglected chronicle of Emperor Galāwdewos (r. 1540-1559). This work is a very important primary source to understand the turbulent period of the 16th century, which witnessed huge religious wars and massive population movements that completely changed the ethnic and religious map of Ethiopia and its surrounding regions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Detail of a wall painting showing Emperor Galāwdewos (r. 1540–1559) with his father and a group of Portuguese soldiers from a 19th century wall painting in the Amhara region of Ethiopia (Photo: Michael Gervers, courtesy of the DEEDS project)

In fact, this chronicle was first edited in 1895 by William Conzelman on the basis of three manuscripts (Fig. 4). However, he neglected two other manuscripts that were preserved in European libraries at that time, as well as a new manuscript I recently discovered in the royal church of Tadbāba Māryām which was built by Emperor Galāwdewos himself! The new edition is accompanied by an English translation and a detailed annotation and was published in 2019 in two volumes in the CSCO series.

Fig. 4. A manuscript witnesses of the chronicle of Galāwdewos, Bodleian Libraries, MS Bruce 88 (Photo: courtesy of Solomon Gebreyes Beyene)

Finally, congratulations on being awarded a 3-year research project by the DFG to work on “The Chronicle of King Śarḍa Dǝngǝl (r.1563‒1597): A Critical Edition with annotated English Translation.” What kind of work are you doing for this project?

Thank you very much! It has long been my dream to work on this chronicle, considering its importance. Thanks to the DFG, I can fulfil this aspiration. For this edition, I will consider five additional manuscripts that were not used by Carlo Conti Rossini who published the first translated edition of this work in 1907.

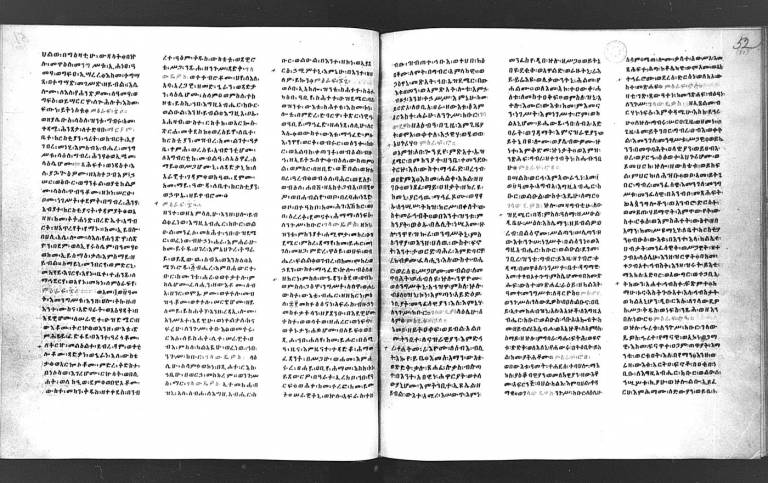

Fig. 5. An example of workflow using Transkribus (Photo: Solomon Gebreyes Beyene)

I started to work on the chronicle in January 2021. My first task was to collate the existing manuscripts (“the process of comparing differing manuscripts or editions of the same work in order to establish a corrected text.”). I have also transcribed the manuscripts using Transkribus (a text-recognition software) and made them available through the Beta maṣāḥǝft platform (Fig. 5). I am currently establishing the critical text by using Classical Text Editor, and I hope to complete the edition by the end of 2022. In the meantime, I will also write articles on the textual tradition and on the contents of the chronicle while attending international conferences. As part of this project, it is also planned to organize an international workshop in collaboration with Beta maṣāḥǝft and other projects engaged in Ethiopian studies on Geʿez text editions and annotation during the third year of the project.

Close

Close