By Sophia Dege-Müller

The Horn of Africa is home to several religious groups and their manuscript cultures. For the project Demarginalizing medieval Africa: Images, texts, and identity in early Solomonic Ethiopia (1270-1527), abbreviated as ITIESE, we focus chiefly, but not exclusively, on Christian manuscripts.

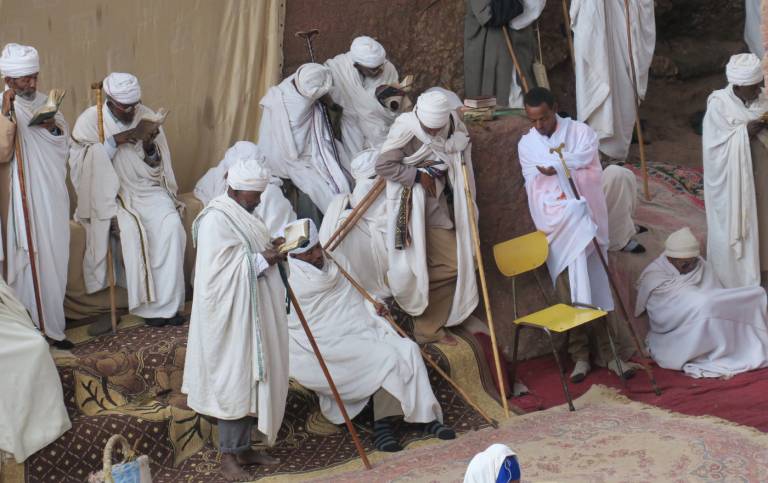

Fig. 1.Orthodox Christians from Ethiopia celebrate the Masqal festival - which commemorates the finding of the true cross (Photo: Sophia Dege-Müller)

Christianity spread across Ethiopia around the mid-4th century CE thanks to the conversion of a king named Ezana. His kingdom – a power player in the Horn of Africa at that time – soon became a Christian nation, where Bible translations and also manuscripts were produced. Around 40% of the population of modern-day Ethiopia still identifies as Eastern Orthodox Christian. The earliest known Ethiopian manuscripts are the famous Abba Garima Gospels, which have been dated through carbon-14 testing to ca. 390–570 CE. These manuscripts, which are among the oldest surviving complete illuminated Christian manuscript in the world, are decorated in stunningly vivid colours and beautiful designs .

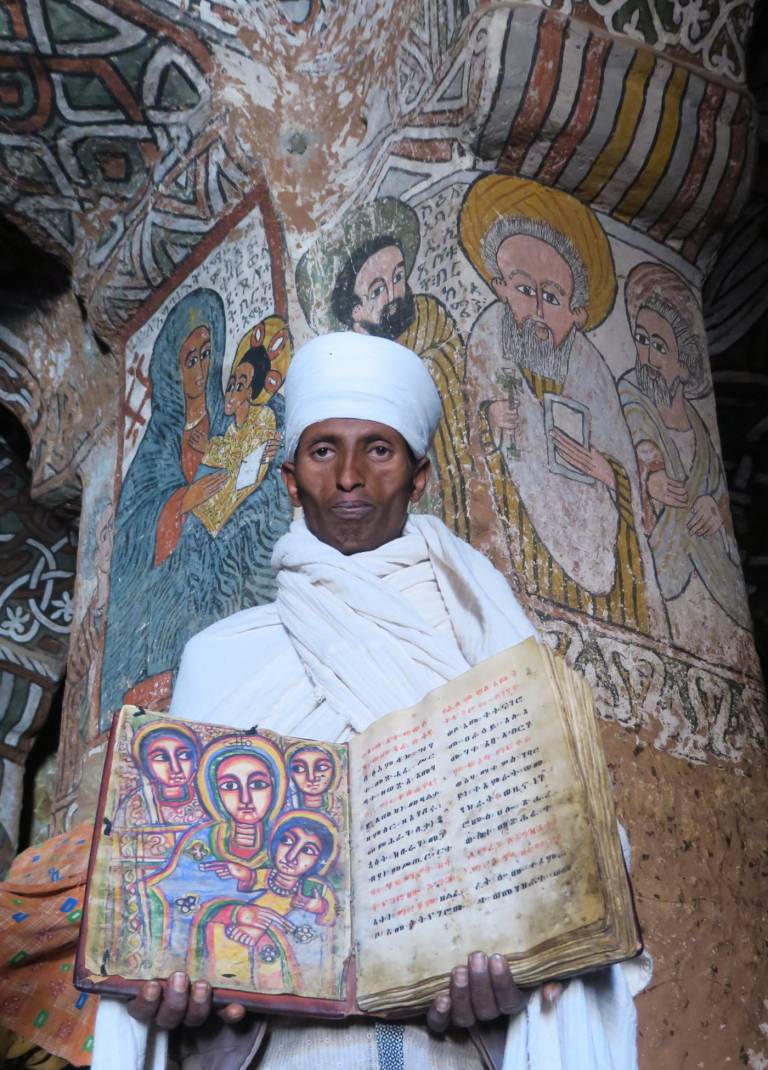

Fig. 2.Priest holding up an illuminated manuscript in a rock-hewn church in Tigray (Photo: Loretta Lynn)

The majority of Christian Ethiopian manuscripts is however much younger, and it is only from the 14th century onwards do we have larger numbers of manuscripts. It is also worth observing that the production of manuscripts in Ethiopia is still ongoing, so we even know samples produced in recent years, and it is possible to watch scribes while they produce a piece. Due to this long-standing tradition the overall number of existing manuscripts is very high and estimated to be more than 200.000 codices (a rough estimate reached by multiplying the number of parishes by the minimum number of books needed to hold church services).

Fig. 3.Priests using manuscripts and books during a church service in Lalibela (Photo: Loretta Lynn)

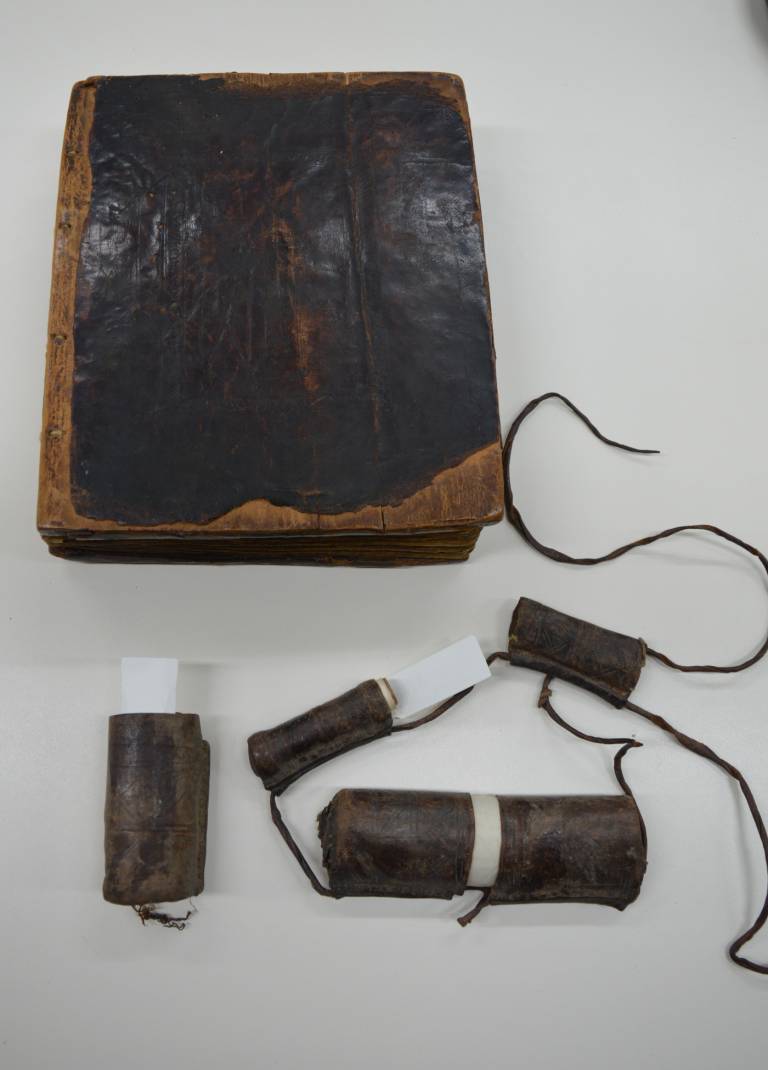

The Ethiopian scribal tradition knows several forms of text carriers. The most used are the manuscripts (codices), while the lay population used to use scrolls with short protective or medical texts. Among the less frequently used types are liturgical fans, or leporello codices (folded like an accordion). Most manuscripts were written on parchment – that is animal (typically goat or sheep) skin – which was locally produced. The pigments for the inks were produced by local scribes by using natural sources such as soot or iron gall ink for black. Paper was only rarely used as writing material and had to be imported.

Fig. 4. An Ethiopic manuscripts and a scroll from the National Library of Israel (Photo: Sophia Dege-Müller)

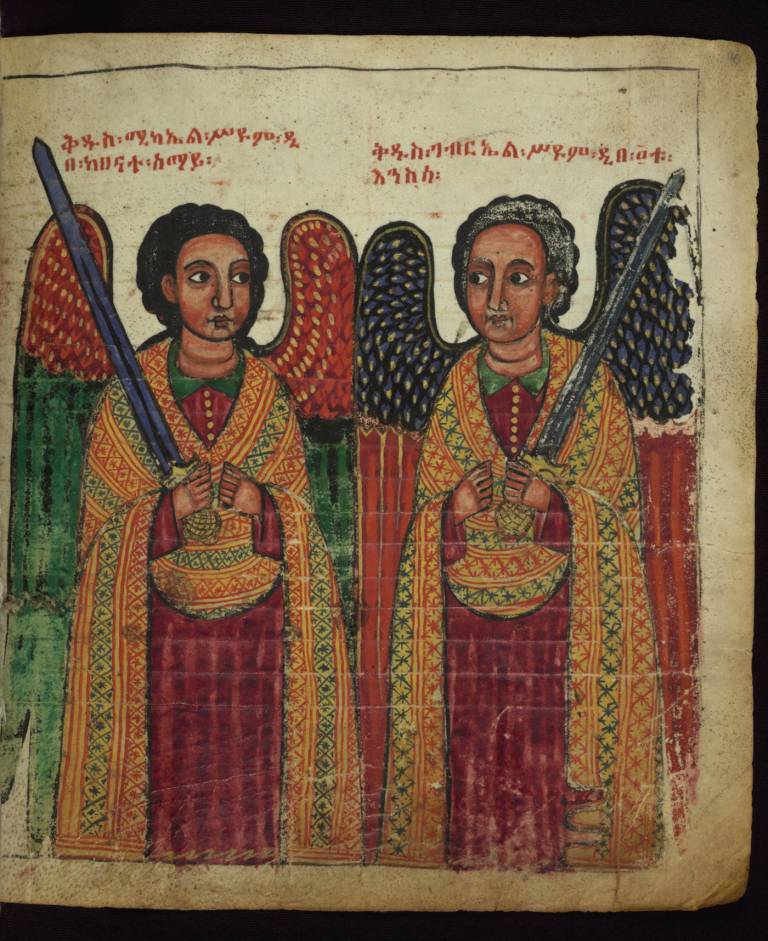

Traditionally churches and monasteries had their own libraries, which are of different size. Smaller parishes usually own just a couple of necessary books, while some larger, and more famous monasteries such as Dabra Dammo or Dabra Libanos host more than 200 manuscripts. These monasteries were equally famous as centres for book making (scriptoria). In some cases, it is possible to trace manuscripts back to their place of origin thanks to notes or their artistic features. Some monasteries, such as that of Gunda Gunde in the modern-day region of Tigray, created their own distinctive style of manuscript illustration.

Fig. 5. The archangels Michael and Gabriel from an Ethiopian Homiliary decorated in the second Gondarine style of painting, Walters Art Museum, W.835, fol. 90r (Photo: Creative Commons, The Walters Art Museum)

In addition to influential places, prominent persons in the Ethiopian past could also have a strong influence on the content and appearance of manuscripts. One outstanding example, in this regard, is surely Emperor Zar’a Ya’eqob (r. 1434–1468 CE). Several manuscripts can be traced back to his royal scriptorium and his patronage. The period investigated by the ITIESE project, which goes from 1270 to 1527 CE, saw the creation of impressively illustrated manuscripts.

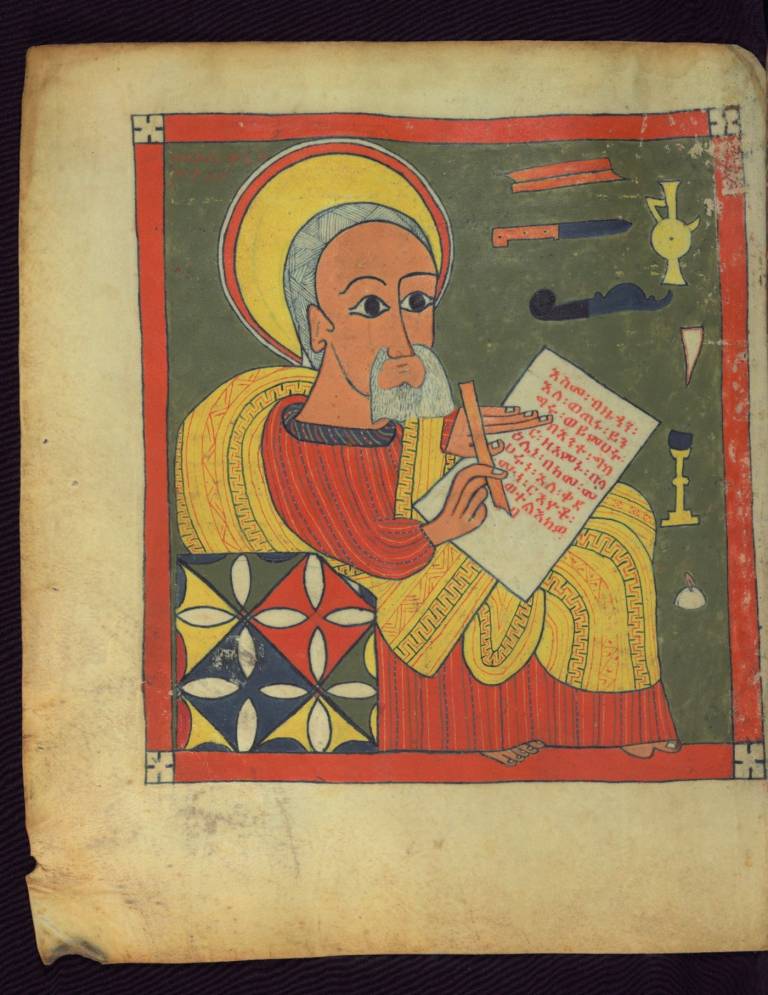

Fig. 6. Portrait of the Evangelist Luke from an Illuminated Ethiopic Gospel Book, ca. 1500 CE, Walters Art Museum, W.850, fol. 96v (Photo: Creative Commons, The Walters Art Museum)

One of the most famous collection of Ethiopic manuscripts was gathered by the Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–1868 CE), who around the 1850s CE established his new capital on a mountain-fortress called Maqdala. For the church of Maqdala, called Medhane Alem (‘Saviour of the World’), Tewodros II commissioned and looted some of the most beautiful and elaborate manuscripts from all over Ethiopia, but mostly from the town of Gondar. In 1868 CE, after Tewodros II was defeated by a British army led by General Napier, a large section of this collection was brought to the United Kingdom, while other manuscripts were given to local monasteries.

Fig. 7. Several manuscripts stored in a church in Northeast Tigray (Photo: Sophia Dege-Müller)

The ancient features of Ethiopian manuscripts decoration have not been studied in a sufficient form, and the ITIESE project hopes to shed new light on the art, history, and culture of Ethiopia and on its links with the other Oriental Orthodox traditions of the Armenian, Coptic, and the Syriac worlds.

Close

Close