By Felix Jones

Gold, showing at the British Library until 2 October, is a small, exquisite exhibition comprising fifty manuscripts. With an immense temporal and geographical scope, the exhibition showcases objects produced from the fifth to twentieth centuries, from England’s northern reaches to the extremities of Southeast Asia. Eschewing a strictly chronological approach, the exhibition takes the visitor through gold’s varied uses on scrolls, maps, manuscripts and bindings, bringing geographically heterogeneous works together thematically.

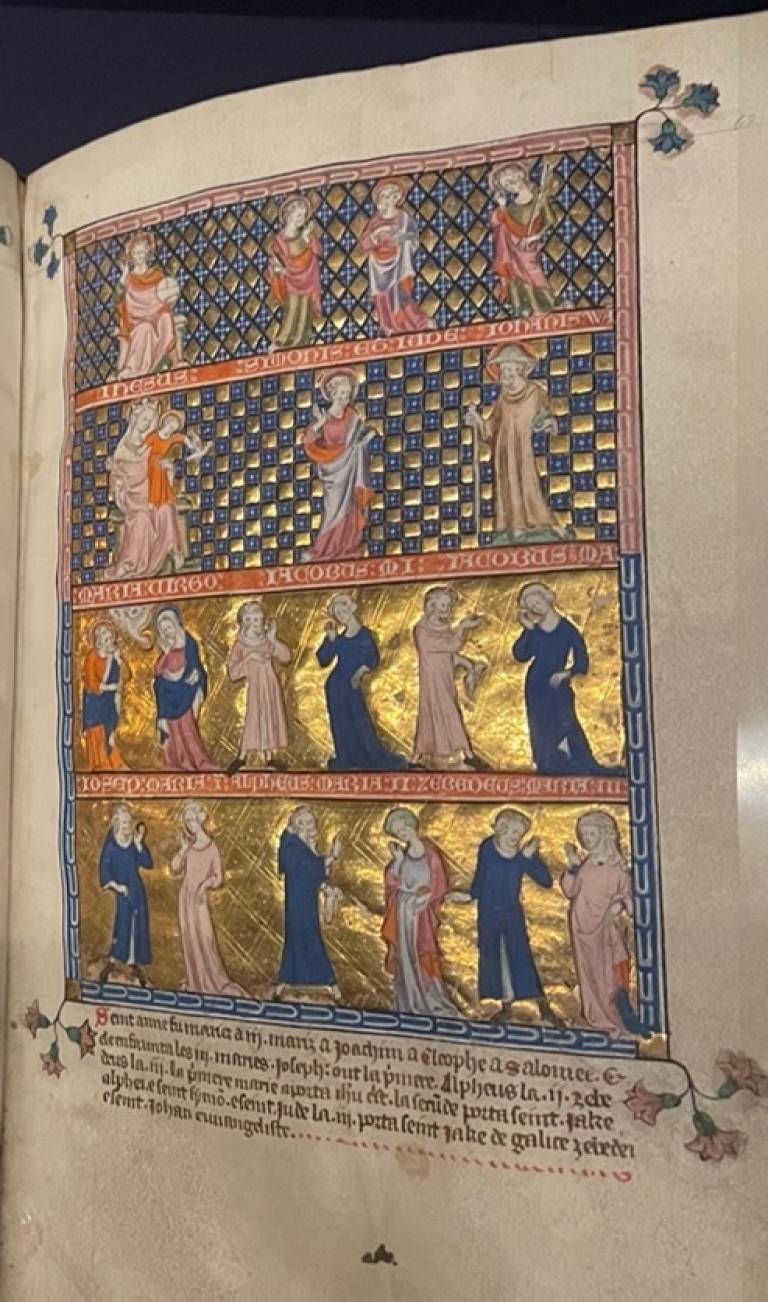

Fig. 1. Queen Mary Psalter, Early 14th century, The British Library, Royal MS 2 B. vii, fol.68r (Photo: Author)

The strength of this highly atmospheric exhibition lies in its ability to showcase gold’s unique, protean visual characteristics. The display of the objects, the majority of which are placed in low perspex cases, makes you view the glimmering pages from multiple angles, peering at the objects from above and below, side to side. Gold can sometimes hide on a page: if photographed incorrectly or viewed from the wrong angle it appears as a dull, brownish colour. This is certainly not the case in this exhibition, and as you pass through the spot-lit exhibits, the allure of the medium is most apparent. In the gold, checkerboard background of folio 68r of the Queen Mary Psalter (Royal MS 2 B. vii), the saintly backdrop becomes a shimmering mosaic with each gilded tessera refracting the light differently, a dazzling, sculptural effect which could only have been more profound when viewed by flickering candlelight (Fig.1).

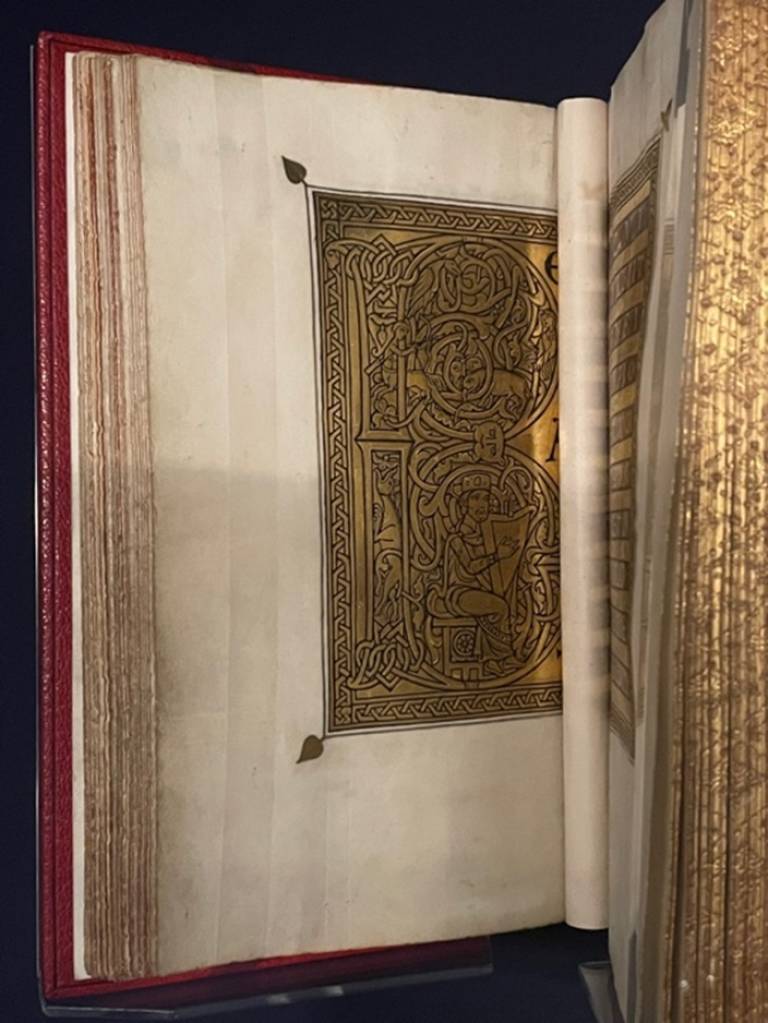

Fig. 2. Psalter of Queen Melisende, ca 1131-1143 CE, The British Library, Egerton MS 1139, f.23v (Photo: Author)

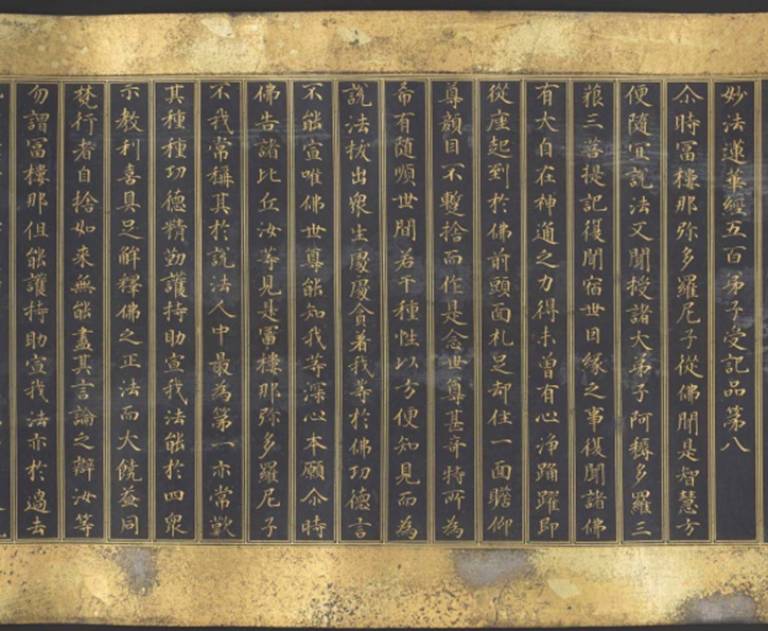

This exhibition also foregrounds gold’s physical presence, whether it’s the medium into which words are inscribed (as in the case of a superb two-metre-long gold scroll, containing a Treaty between Calicut and the Dutch, MS Malayalam 12), or whether it simply embellishes a decorative backdrop within a codex. Gold, when applied to parchment, does not always lie flat and frequently stands proud on the page. In the small twelfth-century Psalter of Queen Melisende (Egerton MS 1139, folio 23v) there’s an elaborate historiated ‘B’, beginning the first Beatus vir psalm (Fig.2). Its border, edged in gold, appears to rise up from the page. Not simply an elaborate initial, this page acts as a sort of trompe-l’oeil, inscribed gold bullion, a golden relief sculpture that appears transposed onto the pages of the royal psalter. This notion of gold leaf being used to mimic three-dimensional objects is a theme that crops up throughout this exhibition, not least with the large seventeenth-century Japanese Lotus Sutra (Or 13926), with its fading burnished edges giving the appearance of a solid metal object (Fig.3).

Fig. 3. Lotus Sutra from Japan, 1636 CE, The British Library, Or 13926 (Photo: The British Library)

This is not an exhibition, however, that sheds light on the process of gold extraction, on its preparation, nor on how exactly gold and its alloys are applied to parchment, paper, or textiles. While this curatorial lacuna leaves many questions unanswered (the process of unrefined gold reaching the workshops of goldsmiths, for example, is alluded to obliquely only by a handful of maps), it nevertheless has its own advantages. We, like many of these objects’ original viewers, are left unaware of the gold’s origin, and its mystique, therefore, persists. As you pass through the exhibition, the brilliant medium continues to captivate, its arcane provenance remaining unclear. Gold’s ‘backstory’ – that is, its journey from first extraction to final application – is not irrelevant per se, but its omission, I feel, makes the exhibition more focused, centred entirely on the impressive collection of objects, and the thoughts and feelings we have in direct response to them.

This, therefore, is an exhibition that you need to meet half-way. It is not comprehensive, nor does it need to be. Its thematic groupings (gold script in sacred text, gold script in profane text, divinities embellished by gold etc.) allow an excellent geographic range of objects to be placed side by side, and it remains up to the visitor to make note of the broader themes, recurrences and cultural peculiarities.

Bio

Felix Jones has just completed a BA in the History of Art at UCL and received the Zilkha Prize in 2022. He was also awarded the Wittkower Prize in 2021. Felix’s interests include medieval manuscripts and their relationship with sacred space as well as the representation of ageing women in early modern painting.

Close

Close