LGBT+ History Month: David Wojnarowicz - 'Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone' (1988-89)

11 February 2021

February is LGBT+ History Month and UCL History of Art will be celebrating by sharing a series of articles about LGBTQ+ artists and their works. In this essay, UCL HoA PhD researcher Louis Shankar discusses 'Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone' (1988-89) by David Wojnarowicz.

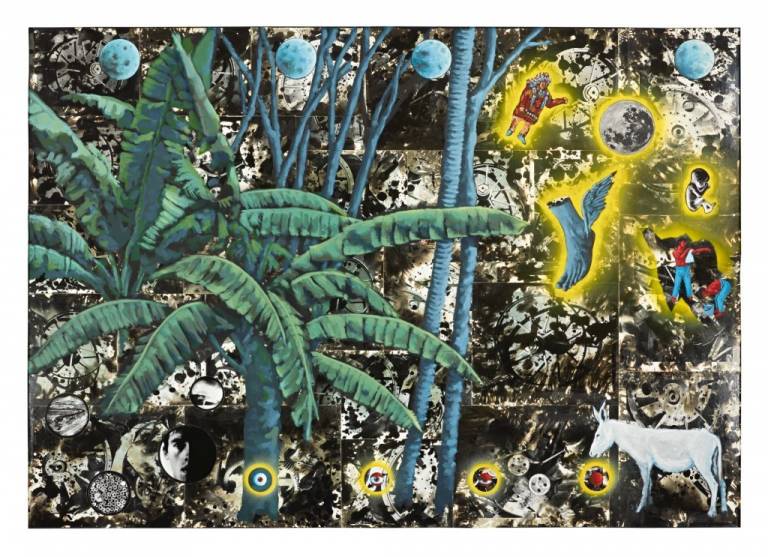

Image: 'Where I'll Go After I'm Gone', David Wojnarowicz (1988-89), accessed via Sotheby's.

Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone is one of several two-dimensional artworks — it doesn’t seem wholly accurate to describe them as paintings, as they incorporate elements of spray paint and collage - created for the 1989 exhibition, ‘In the Shadow of Forward Motion’ at the P.P.O.W Gallery. In the spring of 2020, amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the work sold for $275,000 in an online auction organised by Sotheby’s New York, having previously been acquired directly from P.P.O.W. by the seller. The auction record for a painting by Wojnarowicz seems to be set by his 1986 work, Earth, Wind, Fire and Water, which sold for $1,515,000 in November 2018, also at Sotheby’s. [1]

Where I'll Go After I'm Gone had sold before its presentation at the 1989 exhibition and, as such, is not included on the price list, but similar paintings sold for between $7,000 and $10,000. In this listing, as in the catalogue, the piece is titled differently to at Sotheby’s, as the somewhat nonsensical but altogether more enigmatic: “Where I’ll Go If After I’m Gone”.

As the Sotheby’s catalogue summarises: “A dense multimedia mélange of highly personal symbols, David Wojnarowicz’s Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone is an expressionistic synthesis of the artist’s graphic aesthetic with the urgent political imperatives for which he is best known... Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone brings together nature, technology and mysticism — enduring and omnipresent themes in the artist’s body of work.”

Wojnarowicz produced an idiosyncratic, limited-run, hand-xeroxed catalogue for the exhibition, featuring notes on each of the artworks and copies of sketches, collages and preparatory work. At the start of the catalogue, following “introductory notes” by Félix Guattari, Wojnarowicz writes, “[these ]notes contained in this book are not meant as literal explanations of the paintings photographs and sculptures in the show; they are rough notes, late night tape-recordings, things spoken in sleep and fragmented ideas which at times contradict each other — they are meant as notes towards a frame of reference; a vague gesturing towards that frame of reference.”

The catalogue text that accompanies this painting is read aloud by actor Russel Tovey in a video on his Instagram, organised by Primary Information, who reissued the catalogue last year. [2] Tovey is an openly gay actor and active art collector, who hosts a popular podcast about contemporary art, Talk Art, with gallerist Robert Diament.

This text, the tenth, is one of the most directly explanatory: first, he situates the work against personal and theoretical contexts, the death of his friend Keith Davis, and mortality, respectively; then, he works through most of the imagery in the piece. Nonetheless, Wojnarowicz’s introduction implies that these notes are far from comprehensive; elsewhere he explains that, “Each painting or film, sculpture or page of writing I make represents to me a particular moment in the history of my body on this planet, in america [sic].”

The text begins: “A year and a half ago I was in a hospital room witnessing the death of Keith Davis.” Davis’ death is explored at length in an essay by Wojnarowicz, ‘Being Queer in America: A Journal of Disintegration’, included in his 1991 memoir, Close to the Knives. Davis himself isn’t identified by name here, but some of the same points — dying twice, doctors jumping up and down on him — repeat across both texts. “At least the doctors had finally agreed to stop jumping up and down on him if he died again,” he writes in the essay, “and somehow through all of this I realized how much more afraid of death they were than he.” Davis was a graphic designer who worked at Artforum magazine; they met in the early 1980s and it was through Davis that Wojnarowicz would meet his close friend and eventual biographer, Cynthia Carr.

The catalogue notes continue through this imagery: “The train is the acceleration of time; the tornado the force of displacement in death.” Both images also appear, on a larger scale, in the contemporaneous Sex Series (for Marion Scemama), a series of works created for the same exhibition; the circular inset depicting a magnified image of blood cells also features in two of the series, including the train composition.

In 1990, Wojnarowicz sued the American Family Association (AFA), who had distributed a pamphlet featuring images excerpted from his work in order to condemn the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) for providing him funding. In his testimony, he explains his choice and use of imagery in several works, including the Sex Series. He used an image of a train, “Since it’s a country of planes, trains, and automobiles, the virus will travel in those means of transportation.”

He explains the figure floating at the top of the painting: “the indian chief a cheap WWII doll that for me translates culture into something that can be owned – less than a century ago the wholesale slaughter of indians was common place and they’d have been completely exterminated if not for organization and resistance; today the homosexual in america sustains the same slaughter which is socially acceptable in most areas; witness the judge in texas that recently reduced the life sentence of a guy convicted of shooting two men to death because they were homosexual.”

The so-called “gay panic” defence that Wojnarowicz references here is still legal in 41 American States; it has since also been reworked as a defence for the assault or murder of trans people, making such commentary from 1989 seem tragically relevant today. [3] Such panic was heightened at the time, due to the ongoing AIDS crisis and the resultant scapegoating of gay men; Wojnarowicz would exhibit a piece later in 1989 entitled america, a photograph of some graffiti that reads “fight aids kill a quere [sic]”.

The evocation of “indians” — as in Native Americans — in Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone is rather problematic, as is the the somewhat glib comparison of the two forms of prejudiced “slaughter”. However, Wojnarowicz’s focus is, arguably, on what he perceives as the fundamental Americanness of both forms of prejudice, a targeted and government-sanctioned persecution. In a review of the P.P.O.W. Gallery’s most recent exhibition dedicated to his work — ‘Soon All This will Be Picturesque Ruins: The Installations of David Wojnarowicz’ in 2018 — Lou Cornum, a diasporic Navajo writer, notes: “Though he, like most Americans, viewed Indians through a romanticized lens, at a distance, his interest in the shared death space of those marked as expendable, as well as his repeated invocation of tribes as a form of social organization, reveals the possibility for collaboration beyond life, here together in the wound we’ve made into our world.” [4]

Wojnarowicz liked to look for universal tendencies, often in pre-modern or so-called “primitive” cultures, as alternatives to the specifics of conservative dogma that dominated U.S. politics at the time. “People in various cultures take to bodies of water for purification rites; southern pond baptisms; indians along the ganges river; haitians in voodoo rituals of cleansing: thus the bathing men; something richly erotic to me.” Cleansing in this manner often bookends a life: the first and last spiritual rites, purifying inductions into both life and the afterlife.

Bathing figures evoke desire not merely for the obvious eroticism of their nudity, or the implied voyeurism, but for the act of bathing itself. For Wojnarowicz, there is often an erotic dimension to bodies of water: he recalls in 1963 a dream, “one night of being naked him a stream. Then I stood on the banks of the stream and my whole body shook and white fluid came out of my dick and fell into the river” — a dream of sexual awakening. In Memories that Smell like Gasoline, he writes of a man: “He was really sexy though; he was like a vast swimming pool I wanted to dive right into.”

The text concludes: “I have no plans to go but if I do this is the partial structure of my frame of references.” This work was created not long after Wojnarowicz’s positive diagnosis for HIV; he had no complications or opportunistic infections, though, despite a very low T-cell count, and clearly still had some hope. AZT, an antiretroviral drug used to treat HIV, was first prescribed for such usage in 1987, although effective HIV treatment, the so-called three drug cocktail, wouldn’t become available until the mid-1990s. It should be noted that Tom Rauffenbart, Wojnarowicz’s boyfriend from the mid-‘80s to his death, lived until April 2019 thanks to such medical advances.

There is a subtlety, a quietness to the themes he evokes in Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone. He emphasises this in an interview, in reference to ‘In the Shadow of Forward Motion’: “And in doing this show, what am I facing? I’m facing death; so what do I have to lose? The self-consciousness was different, and I thought, ‘Okay, I have this date for this show and I’lll put in everything that I think of: quiet things, which I usually suppress in my work, things that are beauty to me, as well as what is loaded with violence or confrontation.’”

In an essay on Wojnarowicz, republished in the catalogue for the 2018 retrospective of his work, Hanya Yanagihara writes: “Indeed, part of what makes Wojnarowicz’s work so potent is how sincere it is. It reminds you that there is a distinction between cynicism and anger, because the work, while angry, is rarely bitter—bitterness is the absence of hope; anger is hope’s companion.” [5]

Louis Shankar, February 2021

Footnotes

[1] Available: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2020/contemporary-art-day-an-onlineauction/david-wojnarowicz-where-ill-go-after-im-gone

[2] The reading can be found at: http://www.instagram.com/p/CBmoaJzhoJ9/

[3] Move information available: https://theconversation.com/i-track-murder-cases-that-use-the-gaypanic-defense-a-controversial-practice-banned-in-9-states-129973

[4] Available: https://hyperallergic.com/456909/soon-all-this-will-be-picturesque-ruins-theinstallations-of-david-wojnarowicz-ppow/

[5] https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/07/02/the-burning-house/

Close

Close