Who is the woman behind the polka dots? In this article I pay a visit to the Tate Modern’s Exhibition of Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Rooms to experience the Instagram-iconic immersive rooms for myself, but also to understand more of Kusama’s work and background.

Kusama Statue outside Harrods in London, Photography: Urban Adventurer

You’ve probably seen her towering over the Harrods storefront, sporting her iconic red bob cut whilst painting an array of brightly coloured dots onto its surface. Taking over the art world by storm and securing collaborations with brands such as Louis Vuitton, it’s no surprise that it wasn’t until my third attempt to book tickets for Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Rooms that I was successful. One of the Tate Modern’s most popular exhibitions as of late, Kusama’s show has gained traction all over social media for its mesmerizing and photogenic immersive displays. So popular, that the Tate has had to extend its opening by years to meet demand, the show now impressively expected to run from 18 May 2021 – 28 April 2024. Though admittedly it was the Instagram-worthy infinity rooms that initially caught my eye, my choice to review this exhibition for an equality, diversity, and inclusion article also comes from a desire to spotlight an immigrant artist of East-Asian descent, a community of artists rarely given the opportunity to have solo exhibitions of this magnitude. And sure enough, embedded in the less viral sections of this exhibition is a complex story of Kusama’s experience as a Japanese immigrant post World War 2, her underrated contributions to the 1960s counterculture movement, and her lifelong battle with her mental health. From black-and-white childhood photos to brightly coloured images of her New York studio, projector slide shows to multi-media statues, works of all mediums come together to celebrate Kusama’s rise to fame and the path she paved for future generations of Asian-American artists.

Yayoi Kusama, Walking Piece, 1966, Video/Film/Animation, Photography: Savanah James

Despite securing time-entry tickets to the exhibition, 10-15 minute queues were set up inside to experience the two immersive pieces. While my partner held our spots in line, I wandered over to the wall directly across from the first immersive space to take a seat in front of Walking Piece. Created a few years after Kusama immigrated from Japan to New York in collaboration with photographer Eikoh Hosoe, the work includes a series of photographs displayed through a projector. Wearing a full kimono and carrying a matching parasol in the empty streets of Manhattan, I was instantly reminded of the experiences of my own mother. A Chinese-American immigrant, my mother grew up in a culture where fair skin was considered the beauty standard, and carrying umbrellas to prevent tanning on sunny days was a common habit. However, such a normalized practice to her was strange to Americans in the early 2000s, and oftentimes passing cars would roll down their windows and jeer, “IT’S NOT RAINING!!!” Kusama’s specific use of a parasol in a non-Asian country captured an instantly recognisable practice for her Asian audience, a subtle nod of solidarity to generations before and after familiar with the universal struggles of cultural assimilation and adaptation. These images held an accuracy and personal resonance that caught me off guard, and everything from the elaborately decorated umbrella to the wide-eyed Americans in the back felt like my mother’s own story told by a different narrator.

Immigrating from Japan in 1958, Kusama bravely came during a time of intense anti-Japanese hatred from the Second World War, so in addition to struggling with the hostility all immigrants face, she also dealt with specific propaganda targeting her ethnicity. To further capture this isolation, Hosoe and Kusama experimented by using a fish-eye lense in the early morning streets. This framing sets up Kusama as a spectacle to be watched in a “fishbowl”, and makes viewers increasingly self-aware of their role as spectators. The fish-eyed lens also places her in the center of our eye on an unnaturally and awkwardly large scale, occupying our frontal view with her response to anti-Japanese rhetoric—an over-the-top, ironic embodiment of a stereotypical Japanese woman. Kusama calls out the simultaneous fetishisation and isolation her background creates for her, illuminating American attitudes towards her heritage as she struggled to navigate a country with self-contradicting attitudes towards her identity.

Yayoi Kusama, Chandelier of Grief, 2016/2018, Photography: Savanah James

Screenshot from Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Rooms at Tate Modern || Tate, Tate YouTube video

At this point, it was our turn to enter the first infinity mirror room, Kusama’s Chandelier of Grief. Kusama struggled with her mental health her entire life, and immersive pieces like Chandelier of Grief stand as testament to her determination to create art that was capable of capturing complex psychological states, as well as the expressive benefits of art creation for the neurodivergent. The mirrors in this glass polygon are cleverly positioned, they confuse the eye and make me wonder just how many baroque-style chandeliers there actually are, pulsing, turning, and shimmering on every surface. The simultaneous use of light and darkness reflects on a powerful ability to simultaneously appreciate beauty while feeling deep-cutting grief, to admire opulence and luxury while feeling the emptiness and loneliness in between. Reflecting on Kusama’s early life, her parents were staunchly against her pursuing a career in the arts. Kusama resisted and left, fleeing to America to jump start what would eventually become a wildly successful art career. To stand inside this room is to stand inside her mind, experiencing the joys of such a bright career, whilst painfully aware of the family she defied and the life she left behind. Chandelier of Grief offers a unique visual insight into the emotional toll countless immigrants take upon themselves when they defy their roots and leave in search of opportunity.

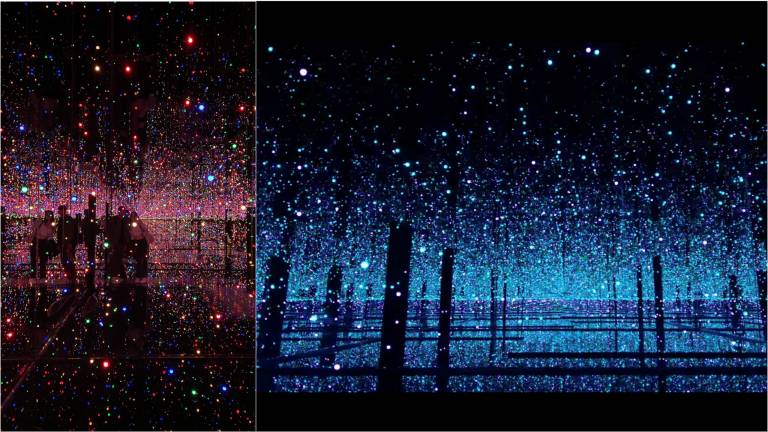

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room, 2011/2017, Photography: Savanah James

Screenshot from Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Rooms at Tate Modern || Tate, Tate YouTube video

The other immersive work in this exhibition is Infinity Mirrored Room—Filled with the Brilliance of Life, originally created for her 2012 retrospective exhibition at the same Tate Modern. Arguably Kusama’s most iconic piece, it is this room that has taken social media by storm and is accredited for much of the exhibition’s success. A shallow pool fills the floor as guests move across a reflective bridge—a symphony of refraction and reflection that transform the space around us into an unbroken and infinite plain. Surrounded by mirrors, the seemingly infinite number of tiny floating dots repeat themselves endlessly on countless reflective surfaces. Constantly pulsing and changing color, they create a space with no end and no beginning whilst serving as a reminder of the ticking passage of time. Plagued by hallucinations her whole life, Kusama coined her frequent feeling, ‘self obliteration’, and invites her viewers to experience it with her in this immersive space. Unable to tell where the art begins and ends, blurring the lines between the art and the art viewer, Kusama requires us to become part of her art to truly experience it. Even as you lose your bearings in this seemingly endless space as you are ‘obliterated’ by her colorful dots, you are made aware of the passing of time as it ticks by, as well as the gallery staff timing your experience to usher you out after exactly 60 seconds.

Yayoi Kusama with Harry Shunk, János Kender, Mirror Performance, New York, 1968, Gelatin Silver Print, MoMA

Screenshot from Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Rooms at Tate Modern || Tate, Tate YouTube video

The last stop on our visit was a series of printed and projected photographs along the rear of the gallery space, which in my view, offer the best summary of Kusama’s mission and most faithfully speak to her legacy. Photography after photograph showed Kusama participating in the radical 1950s and 60s “Sex Drugs and Rock n’ Roll” counterculture and highlighted the true theme that has always been at the center of her art creation—breaking barriers. Kusama was painfully aware of the under-appreciation her art suffered as a result of her Japanese heritage. The lack of success of her more ‘commercial’ pieces compared to her white male contemporaries encouraged her to consider more ‘radical’ art forms, and soon, Kusama was being photographed around phallic sculptures, sticking dried pasta pieces onto clothing, and painting colorful polka dots onto erotic nudes. Once again, Kusama turned to her art to call out society around her, and the maximalist, overwhelming color and content of Mirror Performance speak to the spectacle consumption she observed around her. In collaboration with famous creators of the time such as Harry Shunk and Janos Kender, Kusama shows herself “obliterating” their nude bodies with her signature polka dots around symbols of the torn American Flag, paintbrushes littering the floor, and half eaten food. Including irreverent and unserious surrealist undertones in In the Studio and befriending other big names in the art world such as Andy Warhol, she constantly referenced and celebrated the past work of others whilst pioneering new trends. Breaking down and redefining what performance art could be, she blurred the lines between performer and canvas, between performance and intimacy, and between what could be performed and what could be photographed all within her mirrored studios.

Although Kusama has been in voluntary confinement in a psychiatric hospital since 1977, she is still able to create artwork that feels fresh and in touch with the ways art goers interact with their museums today. By creating popular and photogenic immersive art spaces, she interacts with art trends of the 21st century and predicts her viewers will add another dimension of infiniteness and repetition to her work by posting their versions to social media, breaking down differences between art viewer and art maker. Whether I am pondering on the uniqueness of what only I can see in an immersive space, reflecting on the experiences of my own immigrant family, or imagining how her soft sculptures or hard pasta clothing would feel to touch, Kusama’s true achievement lies in her impact on the viewer and the awareness and critical reflection she prompts in her audiences. Whether she is pushing the boundaries between reality and hallucination, art and the art-viewer, or industry norms and the relationships between artist and the agent, Kusama’s enigmatic legacy and superhuman work ethic rightfully make her one of the most famous names in the art world right now, and Tate’s exhibition barely scratches the superficial surface of what her complex art portfolio has to offer.

Both Infinity Mirrored Room and Chandelier of Grief are incredibly effective in their ability to turn Kusama’s visions into tangible reality and offer a glimpse into her psychology. But the short and carefully monitored visitation times have been called out by many critics and art-goers as preventing us from fully experiencing her rooms and achieving proper “obliteration”. However, rather than target the Tate for the universally felt consequences of art commercialisation and mass consumption, I think this instead speaks to the magnetic nature of Kusama’s work and image branding. Her ability to turn her struggles and trials into her success and weaponise art-making as an effective coping mechanism is an uplifting and motivational story with widespread implications, and the diverse crowds she attracts reflects just that. Although the exhibition’s crowd management isn’t perfect, it is the best shot we have at experiencing Kusama’s work on such an immersive scale. Today, thousands of visitors a day queue to see her “stand up to [us] all with a single polka dot” in her iconic infinity mirror spaces, but in the 1960s when they debuted, they barely afforded her a living. To be so popular as an artist that your biggest concern is crowd control is a true testament to how far Yayoi Kusama has come since she arrived in America in 1958 with nothing but a paintbrush and a vision.

Close

Close