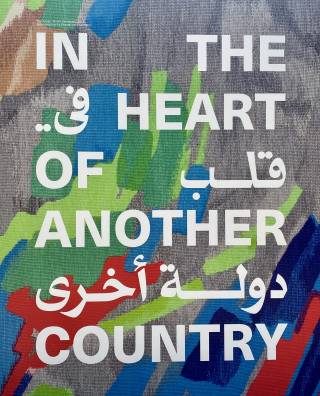

In the Heart of Another Country: The diasporic imagination arises at the Sharjah Art Foundation

Finding shade under the desert trees in the mid-summer Sharjah sun, I take a moment to hear the offbeat call for prayer emanating from scattered mosques. Following unlit lanterns hung on whitewashed adobe walls in the historical quarter, I stumble through open courtyards. Inserted between the remnants of abandoned merchant abodes, I catch a glimpse of six stark white galleries between the meandering alleyways. Carefully opening the door of the first gallery, so as not to disturb the kittens curled up against its cool glass doors, my eyes take a minute to adjust. Upon focusing, they are met with the words “home - longing and belonging”, anticipating the diasporic imagination.

In the Heart of Another Country: The Diasporic Imagination Arises on show at the Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE, explores the collective experience of diaspora told through the foundation's amassed collection. Showing 150 works by 60 artists, the exhibition tells a story of traversed geographies, political unrest, and the search for belonging. The show held in Sharjah is a second interaction - a re-imagination of its debut exhibition at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg. The very movement of the exhibition from Germany, back home to the collection provides an extra facet to its diasporic identity. An image of this ‘diasporic imagination’ is realised as the foundation provides a rootedness for artworks that come from all over the world.

The foundation's collection provides a ‘re-authoring of the history of art’, serving as one of the Middle East’s most important collections for both regional and international artists. Sharjah, one of the seven emirates in the United Arab Emirates, serves as a fascinating site of cultural exchange as ⅔ of the UAE population can be considered as ‘dispersed from their homeland’. Historically Sharjah acted as an important location on regional trade routes, its legacies left through the souks that lay on its creeks. Other than a site of interaction, Sharjah was named Cultural Capital of the Arab World by UNESCO in 1988 and has since sustained its fostering attitude towards preserving heritage through hosting art biennials and adaptively re-using architectural sites across the city for wider art programmes.

The exhibition, described as a ‘choreographed scenography’ of the diaspora, separates the works schematically between six galleries within the complex. Displaying works from 1935 to the present from an extensive range of cultures, the exhibition nitpicks at the nuances of the diaspora and creates an emblematic gesture of intergenerational and transcultural collective experiences of ‘longing and belonging’. Exploring self-representation, the cultural notions of the global south, proposed and imagined architectural forms and the realities of art in domestic spheres, the exhibition, despite its vast scope, finds a central and shared meaning.

This idea of choreography is heightened by the six Al Mureijah galleries which are forcefully inserted between the historic neighbourhoods' structures. Moving between the dispersed galleries, between the dimly lit air-conditioned spaces and the sheer summer sun, the movement between the contemporary and historic, the crossing of boundaries and the adaptation to new environments represents the pertinent and lived realities of the diaspora.

Architecture by other means

The first gallery proposes ‘the mutable nature of geographic borders and architectural possibilities which may be initially difficult to recognise at first glance. Walking through three rooms which display a range of works from film installations, paintings, photographs and smaller sculptures, the theme of architecture does not seem to be their uniting factor. However, as noted in the didactic text, the term architecture is not used in isolation, rather by suggesting ‘propositional architectures’ the potential of material forms become gateways to find home wherever one finds themselves.

One of the first works you see upon entering the gallery is Etel Adnan’s wool tapestry, Mount Tamalpais. The title for the exhibition was inspired by the Lebanese artist and writer’s memoir, ‘In the Heart of Another Country’. Describing her absence from Beirut as “an exile from an exile” during her time living and working between France and the United States, it is no wonder that she looks to stationary forms in nature to find a constant within the worlds she is torn between. During her time in California, she felt a certain fondness towards a Marin Country Mountain she referred to as Mount Tam. Woven within the wool tapestry, mount tam appears abstractedly, as a memory, as streaks of colour emerging from the grey woven wool. Finding belonging in longing, Adnan’s tapestry serves as a wonderful introduction to the gallery’s suggestion of architectural forms and how they can be imagined.

Left: Etel Adnan, Mount Tamalpaïs, 2015, Wool, 170 x 212 cm, courtesty of the Sharjah Art Foundation

Right: Hassan Sharif, Slippers and Wire, 2009, Slippers, copper wire, dimensions variable

Further into the gallery, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmain’s untitled geometric drawing proposes the ways in which architectural forms “weave together tradition and modernist consciousness”. Although her practice was formatively developed alongside the establishment of geometric abstraction in New York, her visits to Iranian Safavid Islamic architecture developed a new facet for her practice. Utilising the geometry inherent in Islamic design within the realm of American geometric abstraction, this sketch explores her cross-cultural influences.

Left: Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Untitled, 2008, colour felt tip pens, mirror on plaster, 36 x 96 x 5 cm

Right: Adam Henein, Falling Flowers, 1976, papyrus, 22 x 357cm

Artists such as Hassan Sharif explore modern consumer culture within the UAE; in Slippers and Wire (2009) Sherif accumulated and assembled plastic slippers in a maximalist sculpture reflecting mass production and consumption. While juxtaposing artists such as Adam Henein create delicate works on papyrus with natural dyes as a way to explore the legacy of pharaonic art making as seen in Falling Flowers (1976). The dimensions, materiality and mutable ability of architecture allow artists of the diaspora to create meaning from an imaginary to create new environments or situate themselves in two places at once.

The Salon

Image: Joana hadithomas and Khalil Joreige, ISMYRNW, 2016, single-channel HD video, 50 minutes

Entering the second gallery, I encounter a familiar scene: a Persian carpet, a wooden sofa and a television. The cultural context of the ‘salon’, the heavily adopted French term for living room, transcends the domestic female experience and instead acts as a window into the lives of art practitioners who balanced motherhood with their practice, or who had to seek social and political refuge. Domesticity never dampened or put on hold the creativity or ability for women to produce art; rather than an easel or a dedicated studio, they made do with desks and sofas. Despite the initial modesty of the works on display due to their small size, subject matter and association with domestic objects, they work as an act of revelation.

A dressing table stands idle in the centre of the gallery with its drawers pulled open. As you approach Lubaina Himid’s Feeling Colour by Touch (2019), the drawers transform themselves and reveal hidden portraits on their inner panels. Himid has said, “I love that thought of opening a drawer and knowing that somebody else's life is coming out of it”. Exposing the ‘half-hidden, half-visible’ realities of others’ lives, the work encapsulates the silent resistance and reality of the lived female experience of creativity, despite the curtains being half-drawn.

Image: Lubaina Himid, Feeling Colour by Touch, 2019, Acrylic on canvas, dressing table, acrylic on wood, dimensions variable

Reclaimed portraits

“What does it mean to reclaim one’s image?”. Entering the third gallery, you are met with gazes of longing, doubt and disguise. The portraits seem to peer at one another across the gallery in a silent and reserved conversation. In Anuar Khalifi’s diptych Talwin Tamkim (2022) the viewer witnesses the negotiation of the figure torn between two canvases and cultures, facing away and towards the viewer. Hayv Kahraman forensically explores taxonomies and disguises of hairstyles and facial hair. Ahmed Morsi’s funerary scene Elegy of Al Gazzar (1968) questions the very representation of humanity through the ambiguity of his sketch-like figures. Although portraiture in a very foundational sense explores the ‘nuances of self-representation’, it summons subterranean emotions and brings the dead to life.

Right: Anuar Khalifi, Talwin Tamkin, 2022, Diptych, acrylic on canvas, 190 x 135 cm each

A wayward ethnography

In Michael Rakowitz's 2018 film Ballad of Special Ops Cody, a figurine wandering through the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute asks “What are these things doing here? What am I doing here?”’. Although this film was displayed in the exhibition's first room, this question resonated with me as I advanced through the fourth dimly lit gallery. In the film the special ops figurine stands among Mesopotamian votive statues taken through colonial exploitation, trying to release them but they cease to move. It is not necessarily the question that worries me, but it is the reality that objects and cultural identities are haunted by colonial encounters.

Beyond critiquing museology and displaying the remnants of such histories, the selected works create a time capsule of sorts that preludes the consequences of colonial encounters. A selection of works such as Lionel Wendt’s portraits of Sri Lankans from the 1930s and 40s on colonial era wallpaper blatantly remind viewers of colonial histories. However, a work such as Latif Al Ani’s photographs document a complex period of Iraq’s history, before the devastation of the Gulf and Iraq wars, but the ‘cosmopolitan possibility in the country’ with the oil trade and tourism. Images of fashion shows at ancient ruins in Mosul and a family of the American Friends of the Middle East organisation visiting the Ctesiphon Arch must be viewed with a tragic sense of dramatic irony. As difficult as it is to see the aftereffects of colonial and imperial encounters, it remains equally tragic to witness the hope and wealth of a such as Iraq country before the United States invasion.

Left: Latif Al Ani, Family from the American Friends of the Middle East organization on a visit to Iraq Ctesipon arch, Iraq, print, 1964, 60 x 60 cm

Middle: Lionel Wendt multiple works from 1930-40

Right: Latif Al Ani, Fashion show at the Nineveh ruin in Mosul, Iraq, print, 1964, 60 x 60 cm

The Colour of an exhibition is blue

The colour blue can be considered one of the rarest primary colours found in nature. Although it is a colour that surrounds us, as it is generated in the sky and paints the sea, perceiving it acts as an ocular illusion. As suggested by the exhibition’s curator, Omar Kholeif, “Grasp the atmosphere and bottle it. Scoop us the sea in a jar and what materialises is translucent. Substances sheer and apparent at times, glowing. They are not blue”.

In a similar fashion, the “assumptions of the diasporic as subaltern, can seem increasingly antiquated for the ethnic Global Majority”. Although the term ‘imagination’ has been heavily adopted as an opportunity to forge meaning and connection among the dispersed artists, the term has equally fallen victim to illusory narratives. From the negative cultural notion of ‘going south’ to the experiences of exile, forced migration and yearning, the diasporic imagination can conjure images of isolation, of loss. In the heart of another country, the exhibited artists have created a testament that materialises hope, perceives longing and ultimately reclaims belonging wherever it is they roam. To take hold of the darkest blue waters and hold it up to the light.

In the Heart of Another Country: the diasporic imagination arises

15 July - 24 September

Close

Close