In this interview, Ana Charriere speaks with Aya Haidar, a Lebanese artist based in London who has developed a deeply singular and socially-engaged discourse through a variety of fascinating projects, from a residency to support the social integration of Syrian refugees in Scotland to the monumental series Highly Strung recently acquired by the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. She is an all-encompassing artist who critically articulates shared stories related to womanhood, displacement, migration and invisible labour, exploring issues of historical cyclicality. Her portfolio, artistic residencies, and social-engagement projects can be accessed on her website.

You can listen, read, or visualise this conversation through the podcast-slideshow or the written transcript which you can find below.

Left: Portrait of Aya Haidar © Photo courtesy The Observer (Photo: Roo Lewis)

Right: Aya Haidar, Soft Labour, 2019, embroidery on cotton muslin © Courtesy of the artist © Photo courtesy Cubitt Artists (Photo: Mark Blower)

Ana Charriere: Aya, I am so happy and excited to be speaking to you today, and I can’t wait to dive into some of the issues addressed by your artistic and didactic work, which is complex and multidimensional in its treatment of labour, displacement, domesticity, womanhood, and memory. I find your practice fascinating because of its social diligence and its pointed engagement of craft practices. You position stitching as a way of writing, inscribing untold stories on dated, found objects, whether this be in your personal artworks or in your workshops, where you provide participants with a framework to process and discuss their lives. Craftwork, through its familial and folkloric character, its relation to the home and to memory, is much more accessible and close to a broader public than genres such as literature. As you express in your Artist Statement, you ‘explore the fundamental elements of language that contribute to a story’, and you do it through visual, bodily means. This investigation also takes place during and through conversation and collaboration, reminding us that storytelling is a continual exchange in which we listen and we speak. Your practice is intrinsically human, and I recognised that from the first moment I saw your work.

As you can do it better than anyone else can, I will now let you introduce yourself. I would love to know more about your upbringing, the experiences which have shaped your practice, and the issues which matter to you the most.

Aya Haidar: What an introduction, that’s really quite humbling, so thank you so much. My upbringing…Well, I’m of Lebanese origin, so both of my parents are Lebanese, and, during civil war, in ’82, they fled Lebanon and got married in Jordan, and then moved to Saudi Arabia. My mother then gave birth to me in America, and then came back to Saudi Arabia, where I lived until I was six. Then, my dad’s job relocated him to London. So, I would say I’m raised in London, but I’ve got very, very strong cultural roots in Lebanese heritage: in the home, in language, food, culture… all of that is very much deeply embedded in me, even though I wasn’t born or raised in Lebanon. Having said that, I did spend my life going back and forth between London and Lebanon, sometimes every six weeks. It’s a part of me that’s very, very important.

Growing up, even though my mom and dad had a very beautiful relationship, I had a very firm matriarchal hand in my upbringing between my mom and my grandmother. I spent a lot of time with my grandmother, every day after school, every single weekend, and she would piece together my history, our history, our stories of displacement, their move, migration… as we stitched and knitted together. The hand of the craft is so tied to me trying to piece together my history and my heritage, that lineage. So that’s really where the craft element is rooted. But also historically, craft is something that is, at least for the culture that I’m from, something so embedded. Historically, women would sit and cross stitch together, or sew or knit, while they spoke of everyday stories, and those stories live on because their children who were at their feet listened to them, and then passed those on. For me, craft is so much part of my upbringing and so much part of my roots going further back to my grandmother.

Then, I went to a French school where the arts and creative critical thinking were pretty much zero, so I went on to do a foundation course in art at Chelsea College of Art, which was a great stepping-stone, a great flavor into the different facets the art world can have. And then I went on to do a B.A. degree at the Slade, during which time I did an exchange at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, and I was introduced to the fiber materials department there, which completely changed my world. It took craft, which for me was very much about the domestic, very much tied to my grandmother, and it transplanted it into the political, since I took courses like ‘Propaganda and Decoration’. I learned how to silk screen print and use a sewing machine properly. It moved the mending and repair element of craft to a much more conceptual platform. My work has always been very, very politically and socially engaged, so I went on to do a master’s degree at the London School of Economics, where that political backdrop was really interesting to me because it contextualized the stories that I was working on in a very different way. A lot of the political, social elements that I was having conversations about, that I was making work on, was really through storytelling and personal experience, it was from my travels and experiences working with communities, and my family, and then learning about the politics, from a more theoretical perspective, and a more perhaps factual perspective, was an interesting backdrop. I did my master’s dissertation in the role of art in democratisation, so I was always interested in marrying the two sides together.

I think it’s a constant evolution. The issues that matter to me the most are the lived experiences that I’m going through in that moment. A lot of my work has to do with generational narratives and my relation to my heritage, that’s always a constant; making work about migration and displacement, because that’s really something that I always try to piece together about myself. But also, it’s so topical, and I really find that exploring those current stories is so interesting because of the cyclical nature of those politics, they don’t seem to change. But then, as I became a mother, motherhood really injected itself into my discourse. This links, again, with the socially and politically engaged thread, because I am interested in […] how the identity of women changes once they become mothers in society, particularly because our labour is undervalued, unpaid, invisible, and it just seems to me absurd and mad. I kind of took on this new facet as a mother, it’s a subculture that no one talks about or appreciates, and it’s insane, even though we account for half of the population. So yeah, it’s my new fascination to explore as I journey through motherhood, it constantly changes.

AC: That’s very interesting how your personal experiences marry with that of broad social groups, and I have a question which relates to what you’ve just discussed. You’ve made several of your artworks throughout the long-term, on a daily basis, using ordinary materials; could you please tell us about working in a ‘durational’ way? For instance, do you think that series created across several months on the daily, such as Highly Strung, allow the viewer to better grasp your experience as a mother and the conception of time as cyclical? Rather than it [motherhood] being conceived as one moment in life, it’s something that continually happens and not only to you.

AH: I think that craft does that anyway, because unlike drawing or mark-making, it’s durational, it’s so time-consuming to work on something for months and barely have anything to show for it […] I’d say sometimes it’s disheartening, but once it’s done it’s so rewarding. Why I personally appreciate it so much, and when I look at textiles in general, I completely know and understand the labour behind it, the work behind it, the patience, the element of hair and detail and endurance behind it. Highly Strung was a piece of work that took a whole year to create because it was 360 individual pieces, where I made a record of an act of invisible labour, one for each day of the year, so there is that number attributed to it, it is about the duration of a whole year. For me, what was the most poignant part of it was the sheer volume that you experience when you walk into the room. So, yes, there are loads of individual pieces, and individually they are interesting because they pick up on each act that otherwise would go unnoticed, so in and of itself it’s interesting to look through them one by one. But, when you walk into the room and it’s installed in its entirety, the sheer volume of it is something that takes you aback. And with that, you see that time is part of it.

Aya Haidar, installation shot of the Highly Strung series, 2020.

© Courtesy of the artist © Photo courtesy the artist and Naela El-Assad

AH: Another interesting thing about that work in relation to time is that, because it’s throughout the whole year, you see the progress of time. Because I was doing an act every day, one of them might be ‘Put on sunscreen on the kids’, the other might be ‘Remember to put the sun hats on’, but then, further down the line, it will be ‘Wrap Christmas presents’ or ‘Wrap birthday presents’, or ‘Sweep up the leaves in the garden’. You can really get a notion of seasons and time, and ageing and birthdays, and celebration, and all of those milestones that we experience throughout the year, as you walk in through the lines of the work. With that work, that’s why it was really important for me not to break it up into individual pieces. So, there were collectors that wanted to group it, but I felt really strongly about it being one whole body, for that reason, for time, and to show that volume. As it happens, the Guggenheim have acquired the entirety of the installation, which I’m very happy about, and it will be permanently installed in the Foyer, and people will talk about domesticity and invisible labour. I think a body of work that big has to be big because it’s otherwise invisible. We’ve made a book of the work as well, like a big coffee table book, which again is very weighty and heavy, and the volume, the weight of the book, talks literally about the weight that we carry as women, as mothers. It’s a limited-edition book, so it’s an artwork in and of itself […] I’m very proud of the book as well. So that work takes on different facets, but it's all about the durational element, the weight, and the invisibility of this type of work.

AC: That’s very interesting, I hadn’t thought about it that way, and congrats! That’s amazing. Alternatively, and also addressing invisible and immaterial labour, I was wondering if you could expand on how certain aspects of creative labour are not discussed. I’m here thinking about In Witness Whereof specifically.

AH: In Witness Whereof is a piece that I created in 2018, it was commissioned for 21.39, which was a big art fair in Saudi Arabia. This predates Highly Strung actually. So, I was interested in looking at contracts and the value that we place on labour. In Saudi Arabia, and in other parts of the Middle East and all around the world, migrant labour is extremely exploited. A lot of migrants have no rights, and no kind of actual worded documents that protect them in any way, and hence why they’re exploited. And so, I wanted to talk about that, I wanted to make a body of work about it. I found a Pakistani migrant labourer, and I discussed with him what would be a fair contract to hire him for his labour, he was a very skilled craftsperson. I asked him what he would want to produce a piece of work for me. We negotiated the price, but it wasn’t about giving him what he wanted first, it was about negotiating what would be fair, what would not be fair, about times, so the hours that he would like to work… Essentially, he said that he’d want to work sitting on a chair, he’d like to sit in a lit room, so the basics of basics, which in and of itself is the political statement, it’s not that he’s asking for a crazy amount of holiday, or health insurance for him and his whole extended family, and a house…No no, he’s asking for a chair, a well-lit room, a lunch break, the basic stuff that we all take for granted. The work itself was him embroidering the contract, he hand-embroidered the contract that we both agreed to. I believe that it was over 3 meters by nearly 2 meters, it was a massive piece of work. And then, the borders I designed and got printed, which was the map of Pakistan and the map of Saudi Arabia overlayed, so they looked like flowers from afar but as you got closer there were the maps and his hand-signing the contract. As you came closer, you saw that it was made up of all these different drawings of the things that alluded to the contract. So, I hired him to embroider the contract. The aim of it was to talk about migrant domestic work, the importance of contracts and of protecting your workers and making those workers visible.

Aya Haidar and Alamdar Houssein Soujad Houssein during the process of making In Witness Whereof, 2018 © Courtesy of the artists © Photo courtesy Aya Haidar.

AC: Amazing, I’m going to move on to your collaborative work, since In Witness Whereof is essentially collaborative. Reading about your work, I have reflected on the sense of care and of taking time mediated by craft practices such as stitching or embroidery. There is an undoing of the ball of thread and the slow process of ‘writing’ something with it which seems to provide a meditative experience in which we return to our memories and externalise them. What effect do you think that stitching has on the participants of your workshops, such as the one recently conducted at Leighton House for parents and carers?

AH: The thing with craft, what I love the most about doing my workshops, is that it’s about the conversation, it’s not about the final project, it’s not like a life-drawing class. Like I was talking about earlier, where historically women would sit together and craft, as they spoke and shared and passed on their stories, that is the magic. So, these workshops that I do with women, mothers, are important because we get to talk, it’s almost like therapy, we create space to talk, and that space is not really existent in everyday society, unless you go see a therapist or your mate. To sit down together and make something creatively and share our lived experience, is not something people do. People don’t stop anymore and have a conversation, I think it’s all the more important nowadays because everything is so fast, because everything is so accessible online, on your phone, you don’t really slow down anymore. Everything needs to be efficient, whereas this actually physically slows you down, you have to stop and it’s slow, you’re embroidering, you’re sewing. This is a very, very slow process, you’re not drawing or making a quick mark, you are very, very slowly creating something that takes a long time, that needs patience, and you’re talking about lived experiences, shared experiences, that otherwise there isn’t really space to share elsewhere.

The mother’s group is a really, really important one, that I’ve done in several locations, and every single time, mothers feel almost a sense of catharsis from it. You’re quite young, I hope you’re not a mum yet, but it’s kind of a world that I’ve only really started discovering. I mean I’m young, and my oldest in nearly 9, so I haven’t even been a mum a decade, but really, it’s like this underground, undercover world that you don’t really see or experience unless you’re in it. And when you’re in it, there is the Instagram life, where you’ve got everyone who looks like a model and their kids are well-behaved, and then you’ve got the reality, where you’re waking up at 4 A.M. or you’re having to do a bizillion night feeds, or someone’s sick on the day that you have to do something… And there’s all the mental and the emotional load, and it’s a lot, it’s so much, and women don’t talk about it, we are not allowed space to share it because it’s just assumed that we take on that role, and we just have this beautifully-painted image of motherhood everywhere else, and there isn’t space to just stop and bitch about it. And actually, when we sit down, we talk about the difficulties, we actually feel that ‘Oh my god, you’re also experiencing that?’, and that’s what’s so magical about it, because we’re actually sharing this lived experience that we didn’t know existed.

But all the same, whether it’s about motherhood, or anything else, at the moment I’m doing a project with pensioners in Hackney at PEER, an amazing institution in Shoreditch that does a lot of community work, a lot of socially-engaged work, really grassroots stuff, and at the moment they’ve got an exhibition about protest in East London. I’m working with this group of pensioners, the ones that were protesting back in the ‘50s and ‘60s in Hackney where it was the pulse of activism. Now that they’re all pensioners, the same shit is coming up, where you have to heat your home and eat, or the fuel crisis, the cost-of-living crisis, all of that. I was looking through the Hackney archives and they’re exactly the same articles, just change the date on them, it’s the same cyclical nature of the problems that we’ve got. What we’re doing is that we’re looking at the former protests and we’re asking these old-school protesters to create these amazing, stitched protest banners about issues they want to protest about now. So we get together in a circle, we’re not talking about motherhood, we’re talking about day-to-day issues that do affect us, whether it’s heating our food, being able to afford this, all of that. This is where, for me, social change happens, it happens in mothers groups, it happens in pensioners groups, it happens where the working-class people are, because they’re the people who experience the hardships most, and so for me to have these sessions where we’re talking about all this, that’s where the pulse is of everything. The craft is almost a platform, an objective platform, where you can just sit and busy your hands while you just talk, and talk, and talk. That’s what I find really interesting, that’s where the two meet.

AC: Yeah, what comes to mind when I think about the ‘mother group’, and an issue that’s not often talked about and that I haven’t experienced personally but witnessed, is the pressure to find a good school for your children, which I think is often placed on the mother. This kind of links to my next question: you’ve done projects for secondary schools, and for children, so, do you think the artist can offer alternative ways of learning which are different from traditional educational frameworks and which are also important? Maybe you’ve recognised this through your own children, not only in those school programs.

AH: A hundred-percent, not just in schools, I really feel that artists create culture, there is no doubt about that, and artists present an alternative way of thinking that the mainstream just does not have. We’re problem-solvers, we create solutions for issues that I believe there’s a bottleneck on, and because we talk, we move, we travel, and we see things in a very different light, we offer alternatives. Definitely in schools, I’ll tell you about two things. One of them are the schools projects, so talking about art, even with my children. If I was to ask any of the students, and I’ve done this, ‘Name three artists’, it will hands-down always be Picasso, Dali, Magritte, or whatever. It will be a dead, white male, and if it’s a woman, it will be Frida Kahlo, that is it, that’s the extent of art. For them, art is a picture on the wall, hung. First of all, they don’t look at art from any other subcontinent, whatsoever. There’s wonderful European artists that should be looked at and celebrated, but there also needs to be an exploration into more universal approaches to art. But then also, art is not just framed on a canvas, art is installation, art is thinking outside of the box, thinking creatively about how you can make a bold statement using materials around you. One of my examples is this boy. In none of my sessions am I interested in skilled drawing or anything like that. So, one of the things I asked them to do was look around you, with all the materials that you’ve got in your room, I’d like you to make a statement about something that pisses you off about the system. And so, one boy, I won’t forget this, he was always getting told off for swinging back in his chair, he got detentions every week, and what he did is that he took every single chair in the classroom and piled them up into a massive wall, into a leaning-back chair wall. I just thought that was so genius, he was basically sticking his finger up at the teachers and saying this is the reason I get detention every week, well here you go, I’m going to make a big, fat wall of leaning chairs. I just thought that was so clever, he created this installation out of materials that he found in the classroom, talking about the very thing that he’s disgruntled about. I really think that when students are allowed to voice their opinions and make a statement about something, they’re very clever and they explore installation, or sculpture, or whatever it is, to make those statements.

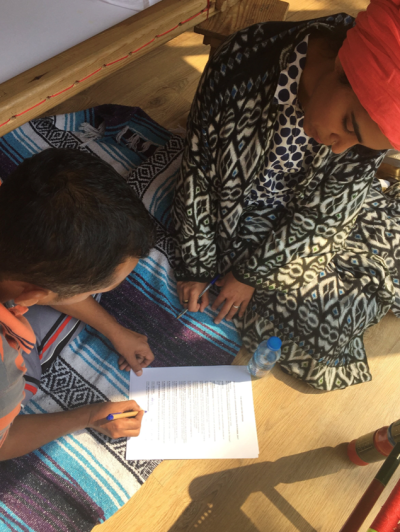

Another example I wanted to use about artists finding alternatives is a residency program that I did in Scotland, at Deveron Projects, where I was invited along with an anthropologist to integrate 120 Syrian refugees into this tiny little town. The local council couldn’t find a way to integrate the Syrian refugees with the local Scots, and so they invited us to find a solution because bigger government couldn’t. What we did is that we compared the two, and we watched how they lived, how they existed, we actually sat and watched and integrated and had coffees and tried to understand who we’re talking about. It wasn’t pages or numbers, it was going out and seeing faces to names. We saw that both came from very impoverished backgrounds, you know, the Syrians we’re fresh off the boat and refugees and the local Scots were going through the oil crash, so there was high unemployment for both sides, everyone was on benefits, public housing, local schools. All of that was the same, but the main difference was that the Scots had very, very bad health, high levels of diabetes, and coronary heart disease, whereas the Syrians were very healthy, and the difference is that the Scots were eating processed foods and the Syrians were cooking everything from scratch, they didn’t have a single tinned anything. So, the creative outlet was in creating a restaurant, a café. On my website you will be able to see, under ‘Residencies’, there’s an eleven-minute video. But, in that residency, what we also did is that, the council was giving the Syrians language lessons every week, and they were completely baffled as to why they were not learning English. And actually, what we did was, again, observe, and talk, and see, and infiltrate, and what we understood is that the Syrians, even back home, that way of learning of sitting at a desk and repeating at the blackboard is not the way we learn in the Middle East, how we learn is just through talking. So, we scratched the lessons, and we introduced language in the wild. I took the women to the local supermarket, to the bank, to schools, to the opticians, and taught them practical language like, ‘Can I have a kilogram of tomatoes?’, ‘Can I register for the GP?’, ‘Can I take out a hundred pounds?’. And the men went with the anthropologist, Marc, and learned about the car, so that they can pass their driving test, so that they can then drive and be more independent, and learned about mechanics and things that culturally they are more affiliated to. So that’s how they started learning English. Artists talk and they converse, and they understand the fabric of society and they embed themselves in it, and that’s how I believe you can create lasting change, because artists see that change and resolve it in that way, rather than looking at stats and figures.

Aya Haidar and Marc Higgin, N.11 Café, Deveron Projects, 2017-2018.

© Courtesy of Deveron Projects, Aya Haidar and Marc Higgin © Photo courtesy Deveron Projects and Aya Haidar.

AC: Yeah, that’s probably the project that strikes me most from your work and I actually wanted to ask you about it, so thank you so much for discussing it and of course I’ll link everything, and I prompt everyone to look at all the projects you’ve done. I’ll just ask a very brief, final question. You’ve participated in many events which celebrate Middle Eastern culture. Who are some contemporary artists that you’ve discovered or met within the Middle Eastern community in London that you’ve found inspiring?

AH: There’s loads of contemporary Middle Eastern artists that I find inspiring for very different reasons. One that I hold real light to is Mona Hatoum, she’s the all-encompassing artist. I’m going to be in a show with her actually this summer at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, and then that’s going to go to the Whitworth in Manchester (I look forward to seeing you there). Emily Jacir is another one, Yara El-Sherbini, Ghada Amer is another one, Monir Shahroudy, loads of amazing contemporary Middle Eastern artists that are making work that I look up to. I look at their trajectory and also how they communicate things, how they vocalise it through their work, which I find so refined and smart and clever and very conceptual. It’s definitely something that rubs off on my practice anyway.

AC: That’s a long list that I will look at! You’ve talked about several things that you’re working on, such as the collaborative work with the pensioners at PEER, or the coffee table book, or the exhibition coming up…but is there any other upcoming projects which you’d like to speak about?

AH: Yeah, so I’ve got these two shows in the summer, it’s called ‘Material Power’, which will start at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge opening on the 7th of July until October, and then from there, it will move to the Whitworth in Manchester. Both of those will have public programs which I’m involved in. There’s the PEER residency at the moment, and then I’ve got a really big solo show in Dubai opening in February coinciding with Art Dubai. That’s all-brand new work which I’m currently working on. The whole show is about womanhood, in fact I’m titling it ‘Battleground’, and that is about women being battlegrounds for…basically everything. So it’s a very, very feminist, very charged show, about womanhood, about motherhood, about feminism, and all of it is new work, so I’m very excited about that. And then a few other small, little projects on the side, more community projects.

AC: I’m looking forward to hopefully seeing several of those things! Thank you so much, I’ll end the recording now so that I can say goodbye to you properly…

Close

Close