This is not limited to what is hung on its walls. From February to June of this year, the program ‘ZIT 8. Potencia feminista’ (‘ZIT 8. Feminist Power) includes exhibitions, talks, performances, screenings and online resources which offer intersectional revisions of feminism, both historical and contemporary. As I do very frequently whenever I’m in Madrid, I spend an afternoon at the Reina Sofia, repeatedly crossing the border between its old building and the 2005 expansion. Through pen and paper, camera and hand, I document part of my ZIT 8 experience, which in a few hours consists of an exhibition on female comic book artists from Spain, a literary round table on non-white feminisms, and a section from the permanent collection which traces feminist and queer initiatives in Spain. I also discuss an online project initiated by the museum which increases the visibility of female artists and thinkers on Wikipedia (which I encourage you to look at).

My visit only encounters some of the events in the program, which is okay, because it is designed in a decentralised and incoherent way for people to come in and out, such that a tourist can learn as much as a gender studies expert who signs up to everything. There is, however, and overlaying, interdisciplinary turn to other ‘material’ practices, from writing, to moving image and performance. The museum-goer transitions from viewing to reading and hearing. What is the impact of this knowing that many visitors come for touristic purposes and expect to solely see Cubist and Surrealist masterpieces? Does this create more ideological division or, rather, an impulse to learn and understand? Although the literary round table attracts many ardent attendees, I am alone for most of the time in the comic book exhibition and hear words of dismay and sighs from the person next to me in the Feminisms Container.

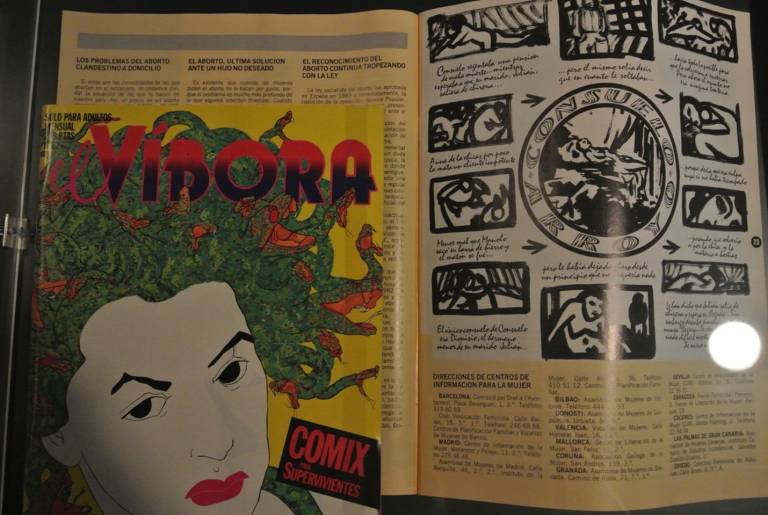

The comics exhibition, which is free to view and is located next to the entrance, looks at individual comic book female authors from the end of Franco’s autocratic regime to this day. During the 1940s and 1950s, this genre was aligned with Francoist values and was mostly produced for younger girls to interiorise misogynistic gender roles. Progressively, and with the reception of feminist magazines from abroad, artists such as Núria Pompeia employed this literary genre in a satirical way, offering new perspectives on sexuality and gender inequality for adults. In the exhibition space, the comic strips are displayed in vitrines which are each dedicated to one or two artists, providing an in-depth representation of the themes, style and publications of individual authors. Additionally, the glass cases are arranged in chronological order according to the artists’ birth dates, denoting a sense of evolution and influence. As the visitor proceeds in a zig-zag motion around the space, they are prompted to look at the walls and windows, which show mixed comic strips from the authors represented in the exhibition. Whereas the vitrines and their captions ask for a political and historical engagement with the illustrations, the surrounding walls prompt a playful and intimate reading similar to how we (and readers at the time of their publication) interact with comic books at home.

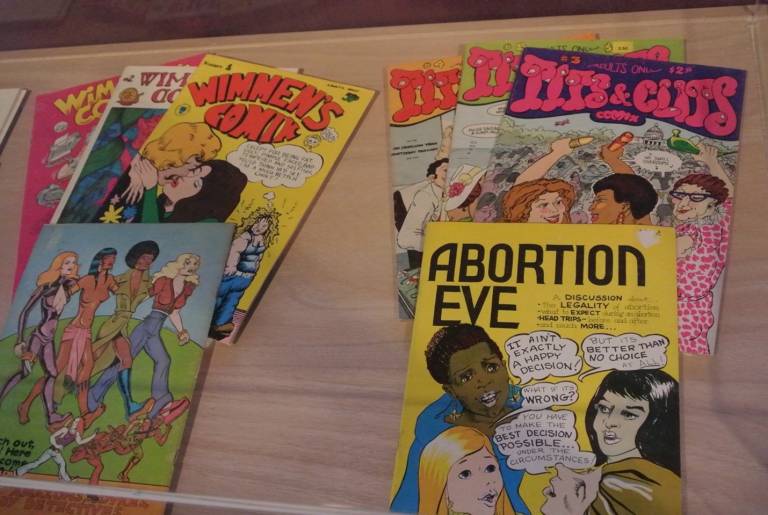

The display begins with the front covers of underground feminist comics from the US, France and the UK, illustrating how, since its origins, this genre was mobilised to portray women’s issues due to its graphic directness and its combination of image and text. The cover of Abortion Eve, a magazine created by Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevly which was based on real testimonies, shows four women in dialogue expressing their different opinions on abortion. By inscribing and making visible the spoken word of women, this publication provides a platform for the complex decision behind abortion, making it available to women who might not be able to have these conversations. Tits & Clits, another US comic, also shows female figures together and in dialogue. As well as serving an informational and didactic purpose, these underground publications empowered readers by providing a sense of belonging to a supportive group in which women-only issues were given importance.

Front covers of underground feminist comics from the United States

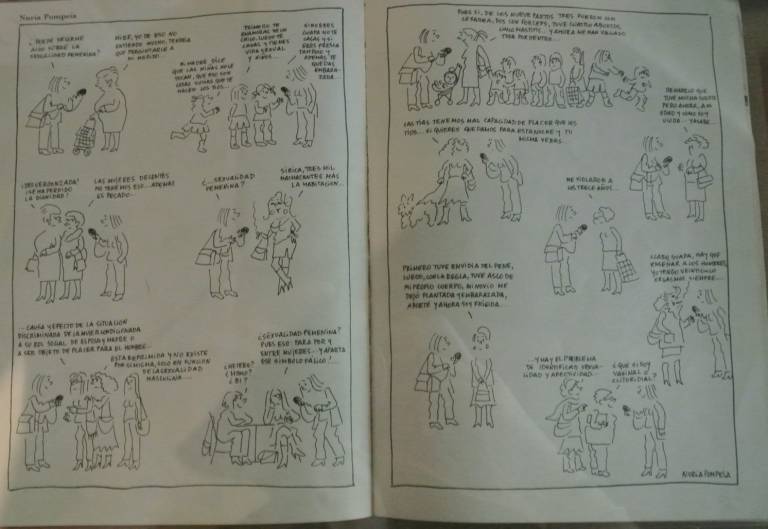

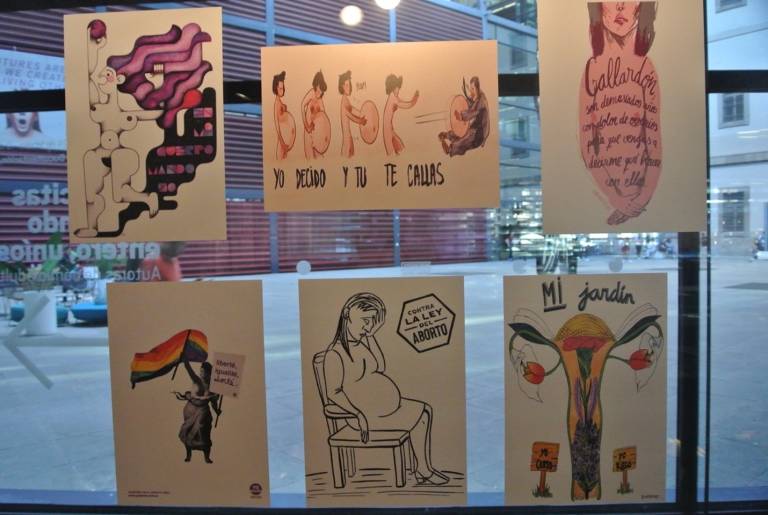

In the Spanish context, the first critical, feminist comic strips had a more minimalist appearance than the colourful, pop style of international magazines, employing satire and humour rather than a direct political approach. In a comic strip by Núria Pompeia, a female news reporter interviews several women on ‘what they can say about female sexuality’. An older woman responds that she would need to ask her husband first, whereas another character discusses her fear of sexual relations after having an abortion. Creating comics at the end of decades of conservatism, Pompeia light-heartedly highlights the diversity of opinions and experiences that exist in Spanish society. Laura Pérez Vernetti, a generation younger than Pompeia, also has a very distinctive, experimental illustration style, which she adapted to a broad range of themes, from mythology to erotica. In post-Francoist Spain, more female illustrators had several roles in the creative industry and undertook artistic training in university, demonstrating that working as an artist was increasingly viable as a professional occupation for women and that they were no longer limited to one genre or topic. The last vitrine is placed against a window from which we see the quotidian movements and operations that occur at the museum’s entrance. Pasted on this pane are illustrations from a 2014 Tumblr project which defended the right to abort. Through this double-view of the museum as a social, dynamic space and of these contemporary, activist creations, we are made aware of our role as informed viewers in the interrogation of the present and the creation of a more equal future.

Illustrations from the 2014 Tumblr Project 'Wombastic"

I cross the square onto the building in front and proceed to the Protocol Room, located next to the museum’s terrace from which the buzzling noises of cars and bars are only faint incidences. The panel discussion held at five addresses the absence of a feminist discourse which is representative of women who are not white, seen through the lens of the publishing industry in Spain. It is a clear continuation of the comics exhibition, which traces the historical intervention of women in the comic book genre, yet it goes further in positing the need for intersectionality between feminism, anti-racism and anti-colonialism in our present museums and written medias. Who gets to write and be published and under what conditions? In what ways is addressing segregated feminist movements as ‘non-white’ limiting?

This panel initiated the series ‘E.L. Queer’, created to foment discussion on literature and queer perspectives by tackling issues related to care work, transfeminism, epistemology and technology, to name a few. In this first session, the moderator Tatiana Romero Reina was joined by Paloma Chen, a Chinese-Spanish poet, Trifonia Melibea Obono, a novelist and political scientist from Equatorial Guinea, and Esther Mayoko Ortega, a Spanish academic and activist. Through an account of their experiences as women and writers who do not occupy a privileged and vocalised position in Spanish society, they informed us on the power we have as readers and consumers to change who gets published. This process of conscientisation begins at the bookstore when we chose a publication over another and ends at the editorial company who receives the profits and decides what writers should be invested in. Mayoko Ortega discussed the power of translation in reinforcing hegemonic discourses. A translator from the UK does not have the same understanding of the world as a writer from Japan, which is reflected in language. This discontinuity between the original text and the translation can obscure the writer’s experience and continue a cycle of discrimination and absence in feminist discourses. Melibea Obono further illustrated this issue: her novels were at times rejected by publishers because they contained terms from a local dialect spoken in Equatorial Guinea, claiming that international readers would not understand them. Rather than expand our terminology to include other global perspectives and decentralise the use of Western languages, the editorial industry privileges what is going to sell the most, which is why we have a responsibility as consumers. These three writers have very distinctive approaches to feminism informed by their culture and their overlooked position in media, posing a challenge for the (unfortunate yet systematic) classification and terminology we use to speak about neglected feminist movements. Chen nuanced that her experience is specifically that of a woman from the Chinese diaspora in Spain, and thusly that she cannot account for all Asian feminisms. Melibea Obono took an alternative stance and defended the need for a unique feminist discourse that employs terminology which is representative of all women.

In two hours, this panel only began to unearth the challenging task that is exposed by intersectional debates in feminism. What is the role of the public museum in staging this ongoing investigation, taking into consideration that it wouldn’t have in the past? As well as providing the material infrastructure, it shares this initiative with a larger audience. More importantly, it brings visibility to the work of the panelists and joins them in conversation, which has a myriad of ramifications outside of the Protocol Room. As consumers, we are made aware of our social responsibility, whilst the speakers are given opportunities for collaboration.

The use of the Reina Sofia Museum’s infrastructure and resources in collaborative investigation is followed in the Wikipedia edition project ‘Talking in data’. Through an intensive use of the museum’s library catalogue, the project aims to provide accurate and complete information about female creators on Wikipedia. As well as democratising data by transferring it from academic sources to a globally accessible open access platform, this collaboration with university students also questions who gets to edit information and how this is informed by gender-related prejudice. This ever-morphing and growing project has also birthed two online resources, a map and a gallery, which group all of the female thinkers and creatives investigated, their Wikipedia entries, and the library publications employed. Although they are written in Spanish, I encourage you to explore the names of thousands of women which have led singular careers and have left an undoubtable impact which needs to be historicised and acknowledged.

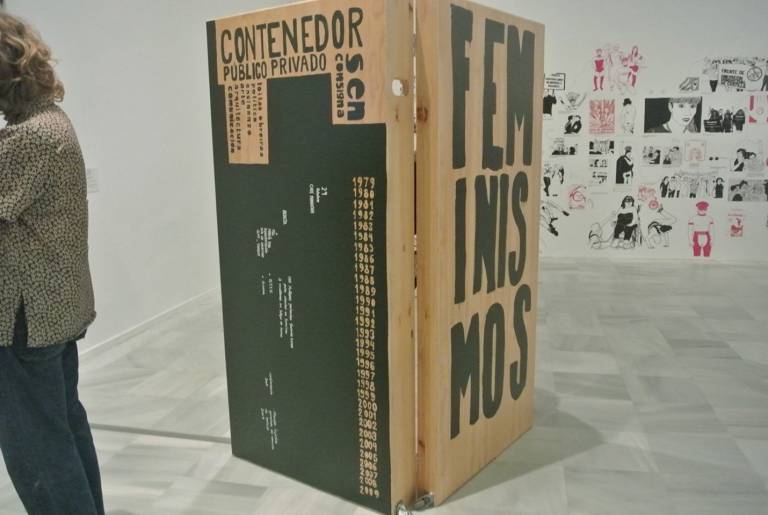

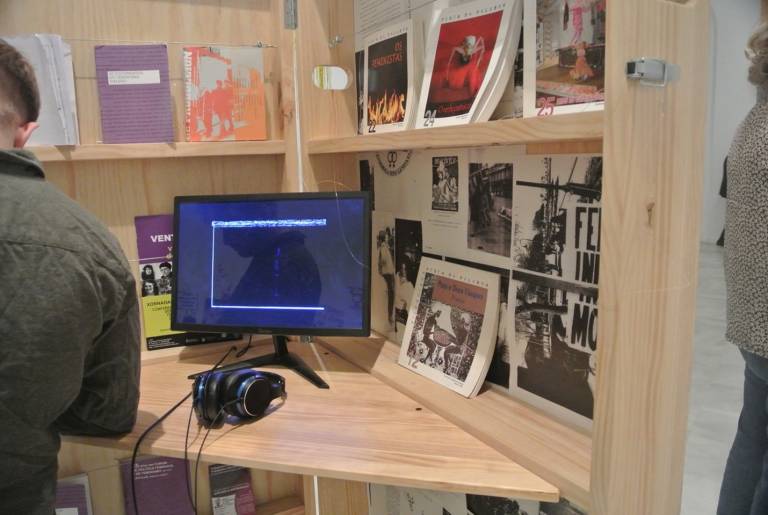

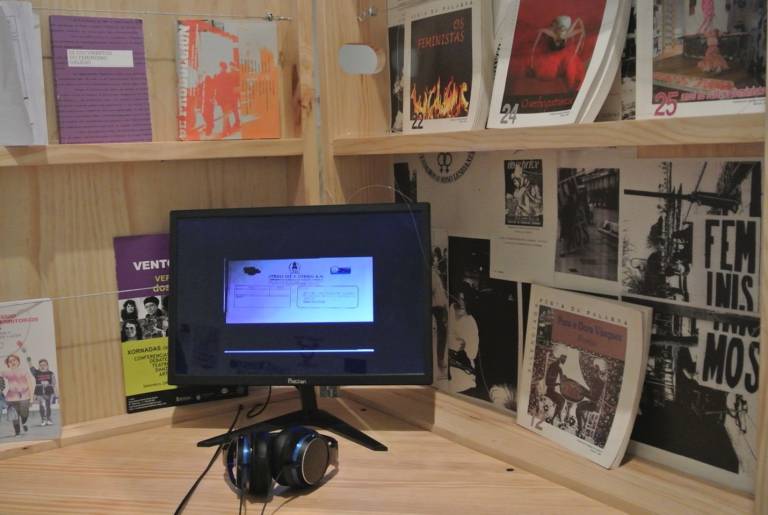

As the cacophonous voice of the museum speakers kindly asks me to make my way out, I pass an open, wooden box, similar to a sarcophagus, with the words ‘Feminist Container’ painted on it. In fear of being reminded to leave by the guards, I move and hide behind it, where I discover a screen and several books strung to the container. Created by Carme Nogueira, Anxela Caramés, and Uqui Permui, this mobile archive, designed to be in the street, traces intersections between feminism and syndicalism in Spain, reminding us of the complex relationship between women and labour. I wonder if it would be a more productive installation if it was outside on a square, where other women would see it on their way to work and could deposit their own archival bits. Nonetheless, this is how a museum like the Reina Sofia can operate, by providing knowledge we wouldn’t encounter otherwise but leaving the possibilities for continuation very open-ended. The public museum is increasingly a structure for collaboration to occur which is accessible to very diverse audiences. It houses debates which in two hours are not resolved, leaving questions in the air for those who want to seize them. It gives historical value and context to popular material sources, such as comic books, showing us that the objects we use in our everyday life say a lot about who we are. As I look back on my afternoon, I am reminded again by the metallic voice that the museum is closing, though I can always come back tomorrow and learn a dozen other things in three hours.

Close

Close