“Chinese and British”: exhibition at the British Library proffers a long-anticipated study of Britain’s under-represented communities from East and Southeast Asia.

Two green-tinted photographs at the doorway herald the diverse contributions made by Chinese communities to British society: one portrays Frank Soo, the first non-white footballer to play for England in the 1940s; the other belongs to Ling Shuhua, a female author whose short novels were popularised in the 1930s and was a close contact of Virginia Woolf. Following their steps, we enter the exquisite lower-ground exhibition room where muslin curtains and wooden screens render a tranquillity far different from the bustling Kings Cross.

The exhibition “Chinese and British” explores the multiplicity of identity, livelihood, and cultural heritage of British Chinese communities, offering a compact and chronological study of the four-century-long history of migration, settlement, and collaboration. From Shen Fuzong, the first Chinese to visit England during the reign of King James II, to the present-day Hong Kong diasporas, the exhibition features personal items alongside books, manuscripts, maps, and photographs from institutional collections across the UK.

The history of exchange began with maps. One cannot miss the precious 17th-century manuscripts of Shen Fuzong. In collaboration with Thomas Hyde, Shen translated major cities and rivers indicated in the Selden Map, one of the first Chinese maps to reach Europe. Shen’s work is followed by a 19th-century map that delineates the settlement of Chinese communities in East London. This section explores how early Chinese migrants in the UK struggled against discrimination and made their livings by running small businesses in Europe’s earliest Chinatowns.

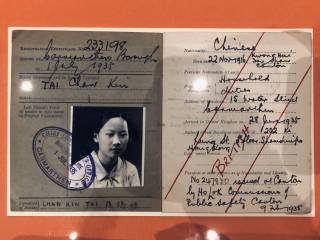

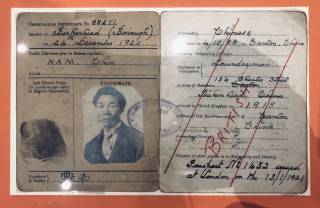

The exhibition also acknowledges Chinese labour forces who fought alongside British troops during the world wars. In WWI, the Chinese Labour Corps constructed trenches for the Allied Power in northern France, and in WWII, many were recruited as seamen and caterers for the Royal Navy. Wartime collaborations are revealed through trench art, personal documents, and memoirs. Importantly, this section sheds light on the forced repatriation of Chinese sailors, many of whom were unexpectedly deported from the UK after their wartime services due to racial discrimination.

Another highlight of the exhibition is a booklet about an extraordinary family called “Hunter Hoahings”. With their grandfather a Cantonese migrant who worked in British Guiana’s plantations, members of this family later became the first Chinese woman and man to pass the British solicitor’s exams and doctor’s exams. One great-granddaughter, Cynthia Hunter Hoahing, also became a tennis player who represented Britain at Wimbledon between 1937 to 1961. Challenging the stereotypes of unskilled Chinese labour, the Hoahing’s story ties into the exhibition’s final section where contemporary British Chinese contributions to science, literature, and arts are celebrated.

However, given the long history of migrations from Canton, Guiana, Singapore, and Malaysia, it is rather surprising to not have seen any direct statement of British colonialism in East and Southeast Asia throughout this exhibition. Although the omission of colonial legacy may help underscore the subjectivity of British Chinese communities, it risks watering down their contributions as mere personal achievements rather than collective and generational struggles. The exhibition’s ambiguous stance on British colonialism may reflect the difficulty in historicising the latest wave of migration from Hong Kong. Reportedly, since the launch of “British National (Overseas)” visa scheme in mid-2020, over 144,000 Hongkongers have moved to the UK to escape the social turmoil caused by Beijing’s new national security law. While the Home Office is “proud to welcome” hardworking parents with young children to land in the UK, many of the newest Hong Kong migrants are only employed in low-skilled occupations that are far from their previous professions.

Despite the exhibition’s meticulous study of objects and peoples, it seems to glide over the tough question of how to properly situate Britain’s colonial past in Hong Kong’s authoritarian present. How might one juggle between the historical mistreatment of British Chinese communities and Britain’s newly acquired identity as “the land of freedom” for those who suffer from their domestic political circumstances? It is as challenging to pose this question as to answer it, just like it takes tremendous courage to “leave behind everything” and to call a new place “home”. In all, the exhibition curated by Dr. Lucienne Loh and Dr. Alex Tickell at the British Library is a long-awaited commemoration of the hardworking men and women who relentlessly shaped, defended, loved the community we call British Chinese, and whose histories belong to both “Chinese and British”.

The “Chinese and British” free exhibition was open at the British Library until 23 April 2023.

Close

Close