An Exploration into The Colour of Pomegranates: Sergei Parajanov’s Love Letter to Armenian Identity and Neighbouring Cultures in the Caucasus Region

Amidst pomegranates that bleed, soaked books drying on rooftops and fragmented folk music haunting dreamlike visuals, Sergei Parajanov writes into history an unprecedented style of film. The Colour of Pomegranates not only pushed the artistic and stylistic boundaries of film as a medium, but it also gave an artistic platform to Armenian identity and culture from neighbouring cultures in the Caucasus region.

The Colour of Pomegranates unconventionally explores the life of the eighteenth-century poet known as Sayat-Nova (Սայաթ-Նովա). Sayat-Nova was a Georgian-Armenian troubadour (ashugh) writing verse in many different languages. Whilst his life may be important in understanding the film, the film itself was not intended to be strictly biographical, but instead uses Sayat-Nova's life as a starting point for a wider exploration of culture and artistic expression in a non-linear and non-narrative way.

Originally the film itself was titled Sayat-Nova, however, "Soviet authorities censored the film because it failed to represent a clear account of the poet's life due to obscurity, inaccessibility... and overabundance of religious imagery". This resulted in two versions of The Colour of Pomegranates - the Armenian version running at 79 minutes and the USSR release that runs at 73. The film stars Sofia Chiaureli (Sofiko Chiaureli) who plays many different characters in the film; Melkon Aleksanyan, Vilen Galstyan and Giorgi Gegechkori also star in the film.

I approached this film with some pre-known facts about Sayat-Nova, however, the film is created in such a way that contextual and factual knowledge is not necessarily important. The film's experimental, anachronistic, avant-garde approach transports the viewer into a world of Armenian heritage. The film pushes a viewer to embrace the multisensory approach and be encapsulated by the film, rather than following a rigid plot or narrative that is spelled out to the viewer. In this article I will be referring to the Armenian version of the film, though some links can be extended to the USSR release, and I will break down the film in terms of visuals, Armenian symbolism, sound, and its presence in the modern world.

Visuals

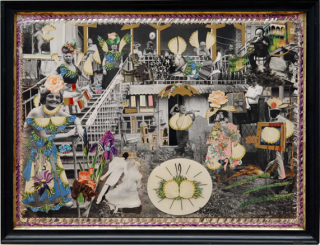

Parajanov’s visuals make this film iconic. Scenes are constructed in such a way that are isolated from the rest of the world. Parajanov achieves this by keeping the camera static and motionless throughout the film. This is emphasised by the film’s square like aspect ratio which may make a viewer feel like they are watching theatre rather than film. Peter Sloane, who has written on the film in ‘Kinetic Iconography: Wes Anderson, Sergei Parajanov, and the Illusion of motion’ claims the film is implicitly broken down - the film is comprised of chapters that explores Sayat-Novas’s “childhood perceptions, sexual awakening, unhappy love affair, initiation into monastic life, old age, and death”. Parajanov's creation of scenes are not always necessarily sensical on first observation and scenes feel experimental and eclectic. However, removing the initial desire to find a clear narrative or plot allows the viewer to embrace the film in its totality. These eclectically arranged scenes are not unique to this film but Parajanov’s oeuvre. Parajanov is not only a filmmaker but considered a highly creative individual with interests in art, music, and dance. For example, his visuals in this film can be compared to his collage work which are busy with expression and have similar visual symbols of shells, religious imagery, and medieval influence. They also reflect the style of Persian miniatures which lack perspectival depth and emphasise the flatness of 2D surfaces.

Watching the film for the first time feels as if you have been awoken from a dreamlike state. There is a sense of composed and ordered absurdity that weaves itself together once passing through scene after scene. To some extent, the film really comes together at the end when certain symbols and visuals reappear when Sayat-Nova dreams about the key events in his life and his youth. This cyclical aspect emphasises the anachronistic structure of the film and emphasised medieval perceptions of time that was regarded as non-linear. This surrealist feel of the film may bring a viewer to compare it to the likeness of the unconscious mind, unconscious inner speech, and the feeling of being within a dream.

Armenian Symbolism

The film overflows with cultural symbolism. It is filled with visual symbols of identity from religious Christian orthodox imagery to the written Armenian language, rugs, animals, traditional dress, delicacies, and manuscripts. The film also references the iconic works of Sayat-Nova. Peter Sloane highlights that the scene itself opens with the pages of Davtar (Daftar) which is considered the most esteemed and artistically valued work of Sayat-Nova’s. However, some of the most important symbolism of Armenian identity can be seen much more implicitly in this film, despite there being plenty of explicit displays of cultural symbolism. Parajanov identified with the eighteenth-century poet and was interested in the collective cultural traditions that shaped the poet’s work.

Both Sayat-Nova and Parajanov were born in Georgia though to Armenian parents. Therefore, both Sayat-Nova and Parajanov in this sense share origins of ethnicity that are intertwined between varying languages and cultures. Parajanov may be using Sayat-Nova to explore his own identity in this film-like setting and as a symbol to the wider audience of Armenian viewers of the intertwined cultural histories we share between other countries and cultures. As described by writer Karla Oeler, “this originality lies in its resourceful solution to the problem of bridging individual consciousness and collective cultures.” Similarly, the film situated in both traditional Armenian visuals and modern Avant-Garde filmmaking acts as a symbol of modern western-Armenians; it epitomises the feelings of being both tied to roots of our culture, like Sayat-Nova, whilst simultaneously growing in a modern and contemporary surrounding.

Sound

Dialogue, speech, and written word is a key element of Sayat-Nova’s work and yet the work itself remains limited in its use of dialogue and speaking. The film uses speech as another form of rhythm and repetition used within the film. It is pleasing to see the Armenian language represented, written, and spoken within the film which is one of the most important features of Armenian identity. The representation of the Armenian language in the film allows viewers, internationally, to engage with an ancient language which may not have been familiar to them before. Whilst sound and language are used throughout the film, silence is also utilised as an important tool. Manusuryan claims himself that “while silence plays an important role in the film, no part of the film was abandoned to mechanical silence - all silences had been worked on.” Each silence was purposeful and added depth to the sequential flow of the film.

Where does The Colour of Pomegranates fit into contemporary sphere?

Close

Close