Jamila interviews Sunny Rahbar, Co-founder of The Third Line Gallery in Dubai, one of the pioneering voices for contemporary Middle Eastern and North African art.

Summary

This interview discusses the state of the Middle Eastern art scene through the lens of three incredible female artists represented by The Third Line Gallery; Farah al Qasimi from the UAE, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian from Iran, and Huda Lutfi from Egypt. Sunny, Co-founder of the gallery, gives amazing insight into what the artists are/were like and how she met them, but most importantly, what makes the artist’s practices so important to mark time and the experiences of Arab women in the region.

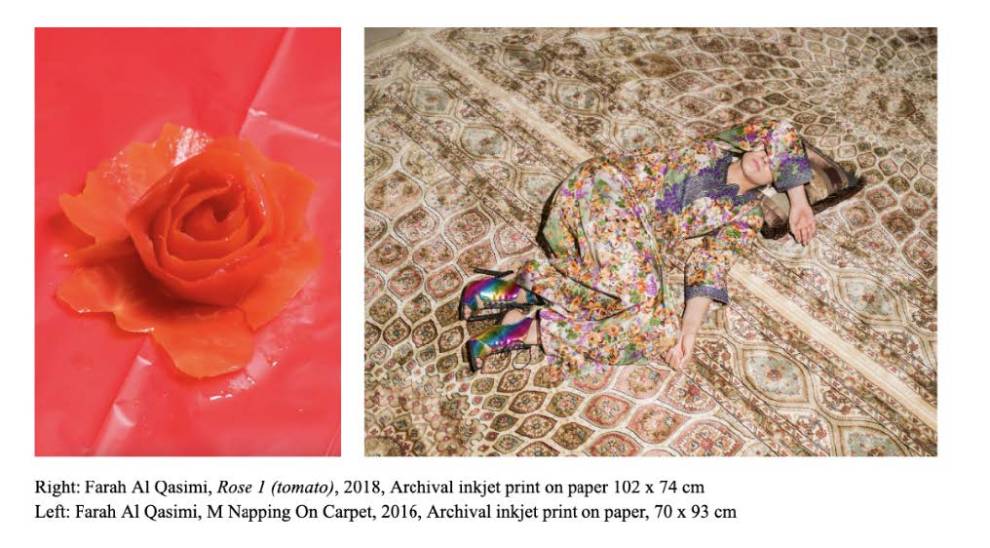

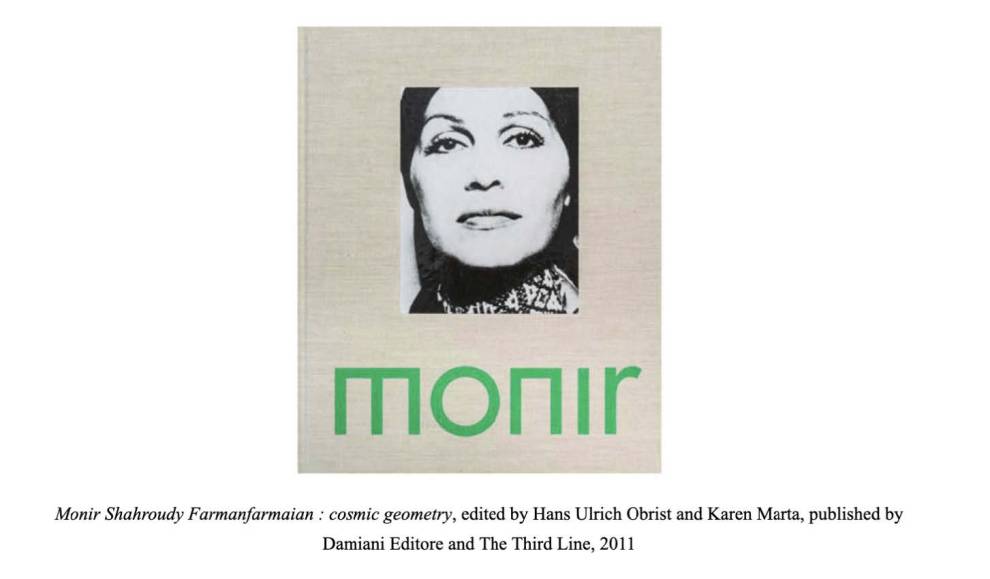

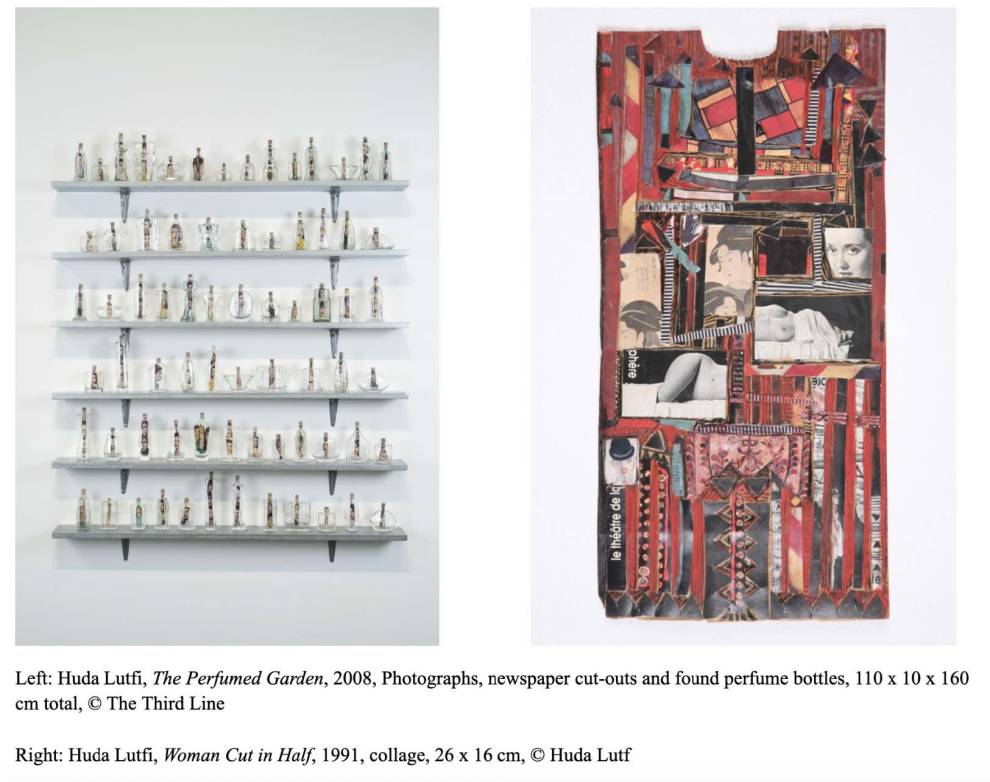

We start with Sunny’s story; while studying at Parsons in New York in the early 2000s, she had to grapple with the lack of representation of artists from the Middle East in Western institutions; upon returning to Dubai, she gathered a group of young emerging artists in the region to give them a platform to support their artistic visions, now known as The Third Line Gallery. In discussing emerging artists in the region, Emirati artists appear affected by how fast the country has changed and is continuing to change. The work of Farah al Qasimi embodies the power of photography to trace the modernisation of the gulf and track the shifting identities of women as they inhabit the UAE when in constant flux. Later, discussing Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Sunny tells her story of meeting Monir at 81 years old and bringing her story to the world before her passing at the age of 96. One particular highlight in this beautiful rediscovery of Monir's work was Sunny's collaboration with Hans Ulrich Obrist on a book to document Monir's life’s work. All our revelations come together as we end with the work of Huda Lutfi. Lutfi utilises traditional crafts and collages which come across initially as an accessible art form for women. However, due to the restrictions on political imagery and art in the region, we uncover how female artists, especially through the work of Lutfi, can hide within collage-making by appropriating the images around them while simultaneously producing new worlds to safely exist in.

Interview

The Third Line Gallery in Dubai’s Alserkal Avenue continues to be one of the pioneering voices for contemporary Middle Eastern and North African artists. Since 2005 the gallery has become an incredible platform to support artists and realise their artistic visions.

Although the international art market has begun to recognise the works of Middle Eastern artists through their representation in art fairs, art auctions, exhibitions and publications, this recognition does not extend as deeply into academic scholarship or the teachings of Art History in Western institutions. The platform produced by The Third Line fills in these gaps in my art historical knowledge. The gallery and its mission continue to propel the works of Middle Eastern and North African art into visibility, which I hope to continue to do for others through this discussion.

I am so delighted to be speaking to Sunny Rahbar, co-founder of the gallery, discussing the practices of Farah al Qasimi, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian and Huda Lutfi, three female artists represented by the gallery.

JAR:

Before we get into discussing the amazing and influential work of some of the female artists represented by the gallery, I would love to know more about the state of the emerging Middle Eastern art scene prior to the opening of the gallery, and how this inspired you to produce such a platform to support emerging artists.

SR:

When we opened the gallery, it was 2005. I came back to Dubai in 2001 after studying in New York. I had really started to engage with contemporary arts. I was at Parsons. I was going out a lot. I was in museums. I was going to gather reasons.

There was very little representation of Arab, Iranian, South Asian or any art that was non-Western. And I was just like, how can there not be any artists from this part of the world that I'm from? And it was this eternal struggle.

I remember I went to a show in New York. It was a show of Ghada Amer's work, the Egyptian artist, at Jeffrey Deitch Projects. I walked in and was first of all blown away. But also... I'm looking at Middle Eastern art or an Egyptian artist or a female artist's work.

There were these canvases from a series she did, there were images from pornographic films or magazines, and they were all embroidered women in these kinds of sexual positions, really beautiful canvases. I was literally blown away. She was using this craft that is very related to women. And I was like, okay, so there are artists.

Of course, I shouldn't say that there were no artists. There was Shireen Neshat and Mona Hatoum. But I was also asking, where are the younger generation? Where is my age of artists? That show was probably very influential in the sense that it really inspired me to want to know more. I wanted to find more.

When I came back to Dubai in 2001 I tried to find and meet artists. It was not that easy. I wasn't yet sure I wanted to open a gallery or anything like that but I still had this burning desire to know where the artists of this part of the world are. So I started to find artists here and there and I met people who would introduce me. But again, these artists were not showing in museums or galleries and then I realised they needed a platform.

And now I was back in Dubai. Dubai was kind of booming and I was like, well, maybe Dubai is not a bad place for a gallery. Or I didn't even say gallery at the time, I said platform. And so it really began like that and it took some years before it actually opened in 2005. And by now I had done a lot of research into artists. And when I met one, I'd always ask them, do you have another friend? So it was like this word-of-mouth situation.

And there were other galleries in the region. Cairo and Beirut had a few galleries. It wasn't just Dubai. But what I realised was that all these traditional art centres in the Middle East were no longer stable places. And so in a way, Dubai just felt like a perfect and safe place for these artists who are not far away. And then the rest of the world was coming to Dubai.

That was kind of the idea. And then it just happened really fast. So we opened and I started to put together the initial list of artists that we wanted to work with. Every artist was just amazing.

And I wasn't necessarily focused on people that were recommended to me or people I spent time with. It wasn't necessarily only women artists, but of course, I was more inclined to promote women artists because I thought, this is definitely a voice that we don't hear. Especially being in the region, it depended on the artist’s practice and what they were talking about. I was also getting tired of the stereotypical works that people thought should come out of the Arab world.

One other important thing is that 9/11 had also just happened. I think that also made people want to know what the hell is going on in the Middle East. What is this place? Who are these people? What are they? And I think a lot of people turned to artists. Artists are telling the story, right? These are the truth sayers. These are the people who are on the ground.

So that was what began, let's say my story with artists from this part of the world. Now it's very different. This year we'll turn 19, which is crazy. But it was just unbelievable at that time. It was a lot about discovering and searching and now these artists do have a platform and you do see them in galleries and you can go to a museum that has collected their work or is including them in an exhibition or biennial. So a lot has changed in these 20 years, I would say.

JAR:

Talking about artists from the region, especially from the UAE, I just had to bring up the work of Farah Al Qasimi. The Abu Dhabi-born artist works with photography, video and performance. Her use of photographs, especially of domestic spaces, consumer culture, and the modernisation of the Gulf, it kind of creates an image that, for me, language and memory can't really express. As I grew up in Dubai, she creates such a nostalgic yet uncanny portrait of the UAE.

There was this quote I loved from the writer Christopher Joshua Benton, saying that her work is a “brand of Gulf futurism that acts less ironic than her contemporaries, but probably more complex, offering up a sentimental, nostalgic and critical window that is world-building.”

As her work conflates consumer culture and cultural tradition, I was wondering how you think her photographs may become sentimental.

SR:

Yeah, it's interesting that quote, actually. When I came back to Dubai I was very interested in Emirati artists because this is where I was living, right? I grew up in Dubai, but the UAE is very young in its history. Compared to Lebanon, Iran, Egypt, Syria, it just turned 50 or 51 in terms of it being established as a place.

There were also a lot of women artists, because I think that it was okay to be an artist if you were a girl. Again, things have changed a lot since then. But what I realised about the artists that were working here of my generation was that a lot of their work was based in their identity. Because the place had changed so fast, and it continues to change, it was almost a way of holding on to something that is changing every moment. It was usually photography based because I think that's also the medium for something that's moving fast, right? You capture it and then it's gone. And that's what I sort of thought was interesting because a lot of the work is about their identity, but also their culture is changing and their traditions are changing, and they are changing in the sense of how they're a woman in this new place.

So from the beginning, yes, I would say that perhaps Farah's work also comes across in that same way that it might be nostalgic. I don't know if that's necessarily the best way to define it though, because I think now if you see her work, she's doing a lot of other things that are not images from this part of the world or inside people's homes or her father's room or of her and her friends somewhere. I think it was more about commenting on these power structures that existed within the region. For example, why did we have this kind of furniture? Or why were these baroque fabrics used? What were these interiors of choice?

She also did a lot of things with food. I don't know if you've seen these very decorated pieces I love, called Rose Tomato. And for me, again, that is something I'm like, oh they are in the buffets you found in Dubai. I think her work is as much about nostalgia as it is about the sort of postcolonial moment in due and how that was articulated and where is it going from here?

So, yes, people reference ‘Gulf Futurism', much like, let's say Sophia Al Maria's work references Gulf Futurism. But I think, again, every artist makes work in relation to their reality and what they are experiencing and what's happening. So yes, definitely that's Farah when she is in Dubai. But I'm excited for what's coming next and to show this next body of work we're showing next year. And I think people are going to be a bit surprised. She doesn't want it to come across as sort of exotic. And that's the danger I think all artists from this part of the world may face. Right?

There's one piece that's her friend on a carpet. That's one of her most iconic pieces. I think, for me, when I saw that piece, of course, you see that it's a carpet from the Middle East. But for me, I think there was an element of this sort of play or this coming of age or women together. And that's how I feel when I see Farah's work. You're seeing something that maybe you shouldn't be seeing. You're just a voyeur in this image. And I think that's what she creates, and that's what she captures. You want to look and you want to understand what's happening. It's very intimate. Even her character, she's kind of melting into the image or the patterns, but also maybe disappearing into the carpet. There's, again, so many layers. And these are, of course, things that you don't see. These were not images that you would see of women in this part of the world in those scenarios.

JAR:

What I find interesting about Qasimi’s work is her examination of Western influences on the Gulf. It makes me think of the work of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian and her practice.

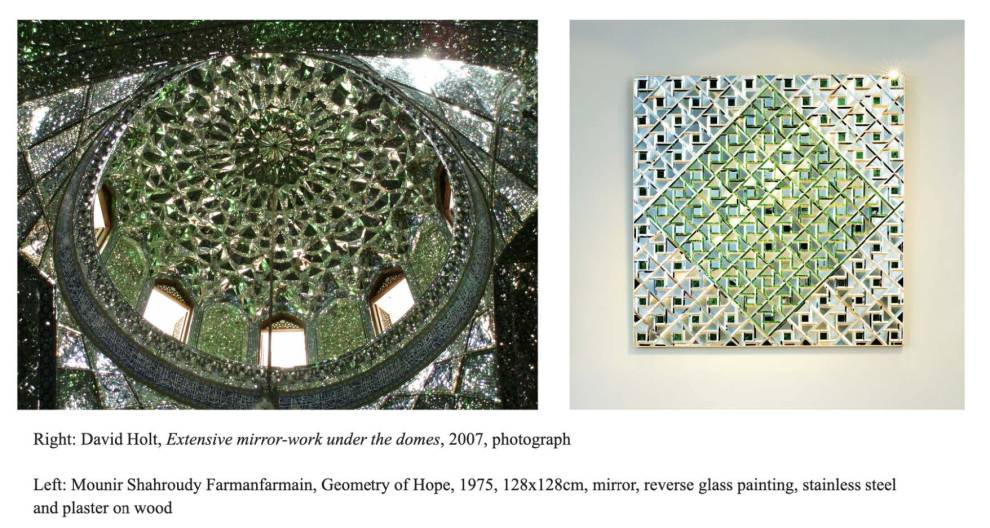

As an Iranian artist who was working transnationally, her work is just beyond anything I've ever witnessed. She explored the possibilities of endless geometry through using mirror mosaics, reverse glass painting, drawings, even plexiglass.

As I've been writing more essays on her and discovering the works of Middle Eastern artists, despite it not being taught in my curriculum, I found a lot of the time her work is categorised under the traditions of Western geometric abstraction, which is obviously a super important facet of her work. But, her seminal focus on sacred Islamic geometries, Sufi ideology and the mirror in Persian artistic tradition is obviously still really important to read in her work. And so, I wanted to ask you, as an Iranian, what does her work mean to you?

SH:

When I first met Monir, she was 81. And she passed away in 2019 at the age of 96. That was the period of her life that I was a part of and gratefully. I just felt very honoured to have had that experience. But we forget that Monir's work was really discovered later in life, but she was making work from the 50s.

She was in New York. She left Iran very early. So a lot of her influences would have been from America. She was at Parsons, actually, in New York, and she also went to Cornell. Her peers were these artists of America, so actually, in a way, when people say that it's on the side of Western geometric abstraction, yes, I think that because she was amongst that same generation. But I think about later on in her life what she was doing, you have to keep in mind that she wasn't able to make the mirror works until she moved back to Iran.

Her career was interrupted by so many points. At one point, she leaves with her first husband for America. She's a young student. And then she has a child. She and her husband got divorced. She's in New York, working and a single mom. But she's doing art, but she's not yet doing her mirror works. And then she falls in love with her second husband, and they move back to Iran together. I would say it was in the early 70s, before the revolution.

So she's in Iran, she's married, and as she says in her memoir, the Iranian mosques are very different. The Shia mosques she visited are very decorated. I think one of them was Shah Cheragh. And she looks, and she sees these mirrored rooms and the domes and the light hitting the mirror and just reflecting off of the surfaces, and she was just mesmerised by what she's seeing. That this is a Persian craft, that craft of mirror mosaics is passed from father to sons over generations. In fact, it's now a dying practice. It's not something that's continuing, and it's all made by hand. It's pieces of glass or mirror that are cut and put on plaster, that's put on wood. It's extremely difficult. You can't do it with a machine. And so she's then inspired by this, but then she's obviously got this background in her education and art which is very much Western-centric.

So now she's marrying this, you know, very Iranian craft with her ideas of art from the Western canon. And I think her early explorations were just trying to figure out how to make these pieces. And then also she realised that she needed to work with craftsmen that actually knew how to make them. And then she wanted to take this craft and bring it into another kind of contemporary space or make it something that can also continue the tradition

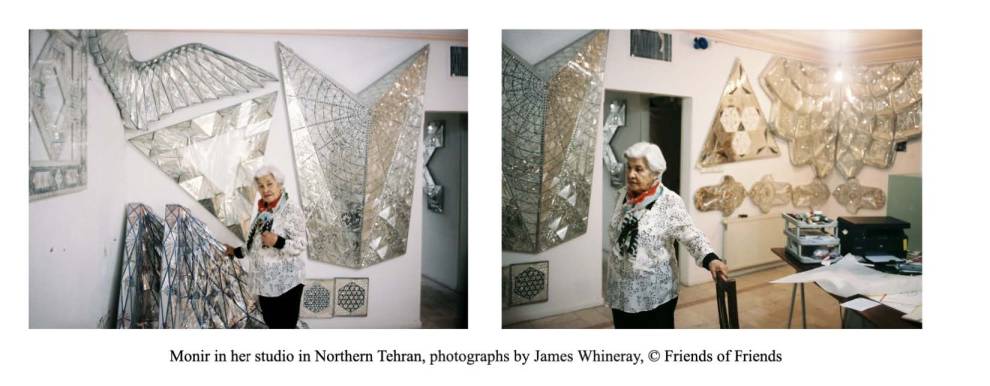

She was very interested, I would say, in architecture, structures, and geometry in Islamic architecture as well. And I think she started to take a lot of the ideas of sacred geometry that are present in Islamic art and architecture and apply them to her forms or mirror mosaics. And eventually, they became sculptures. When I met her at the beginning, she was still doing wall pieces. But the whole time she was doing works on paper, and I think that's what people don’t realise, she has a huge practice as an artist that works on paper and non-mirror mosaic pieces as well.

Towards the end of her life, she was really thinking about architecture a lot. She really wanted to do these large-scale projects, even minarets, or things that you could walk inside of and be underneath.

JAR:

I would also love to know what visiting her studio must have been like in Iran, especially as she was going into the final stage of her artistic practice.

SH:

It was amazing. I was introduced to her by Rose Issa who, at the time, was I would say the only other person that I knew who was working with Middle Eastern artists and was kind of a mentor to me. So I was in Tehran for a family wedding and Rose reached out and said I should go to the studio of Monir in the North of Tehran. She gave me the address and I went there and it's a small studio, but you walk in and there's natural light coming in through the windows and all the works are hung everywhere and leaning on things and the light is coming in and bouncing off everything. It’s the same way she expresses how she felt when she was in this shrine.

And then I see this older lady, with her short cropped all-white hair. Her work gear was this button-down shirt and she had headphones on and she was kind of moving her head. And so I say, “oh, hi”, and she takes them off and says “Hi!”. She was listening to some music that her grand-nephew or niece had shown her on an iPod. And I just felt that I had arrived in Aladdin's cave or something, it was a treasure box. And that was it, we started speaking and I spoke to Rose and said the whole world needs to know about this artist.

So we did a show shortly after that studio meeting, maybe a year later at The Third Line. Honestly, it wasn’t very difficult, after people saw the work through the context of the show and understood more about her, I think everyone must have felt the way that I felt when I first saw her studio.

Hans Ulrich was amazing and I have to say championed Monir’s work. He was the one who said, “she needs a book, Sunny”. There's so much work and there's so many things that need to be known about her and you’re not going to be able to achieve that in exhibitions. There needed to be a book, also so other people could write about her. He had images of all these works she did before to make a record of her life's work. So I said, yes absolutely. At that point we hadn’t done books, we were still a young gallery. So he really helped us and so the first book was published by Damiani. Hans Ulrich was the editor and basically he interviewed her, several times actually in her lifetime, but that was the first time. And Karen Marta worked with us on it; she did a great job. She had so many writers. Hans also said we should get other artists to comment on her work, and how they were inspired by her.

JAR:

Definitely. I have all those books from UCL’s library, I permanently have them checked out and I am always going through them. And the interviews with Hans Ulrich are just incredible as well. She's just amazing.

SH:

It's so candid about her life. The biggest thing about Monir is that she had an incredible memory.

JAR:

Recognising artists, even towards the end of their careers or even as they're older, is so important, especially through publications.

As I'm sure the art of Monir speaks to you, the practice of Huda Lutfi continues to affect how I see the Egyptian cultural landscape. As I'm studying Art History, I'm constantly grappling with, what's more important, the historical or the visual realm. And where do they come together? And where is it that I most find myself? And so the questions her practices ask does that for me as I continue to understand my country's artistic memory.

As Huda has no proper artistic training, and studied as a historian, I found her use of collage and what she says about it giving her more freedom to explore the Egyptian cultural field, more so than academic research, to be really interesting. As a historian, she is able to apply new structures to study old constructions of art historical narratives. Coming to terms with Egypt's colonial past, patriarchal structures, and nationalist conditioning.

So I was wondering, how do you think the medium and practice of collage has been liberating for her, and how can it reinvent how we learn about history?

SH:

I suppose, if you wanted to have a visual for how we put together historical research, Huda’s work is the perfect example. When I first saw her collages, I remember thinking that I was learning about something that I didn’t know. I imagine the environment of Cairo is also very similar to her colleges. It's just this busy place with lots of things at any moment, you're seeing so many images.

And a lot of the work is about re-appropriating, taking something, an object or just things that she finds in the Cairo souks and reappropriating them into something else. I feel that the only way you can visually do that is probably through college. In many ways it's putting together many different things to tell one story, visually. And she does it incredibly well.

When I first met Huda, I was just in love with her spirit. She's a true activist as well.

In terms of her earlier work, a lot of it was about these iconic and strong female characters. But they always had something missing, like a limb. As strong as they were they were not able, and I thought that was just so powerful. It's not just an Egyptian woman’s reality, it's also probably all women, you know, I think that really we feel that. But also not necessarily putting them in a position of weakness.

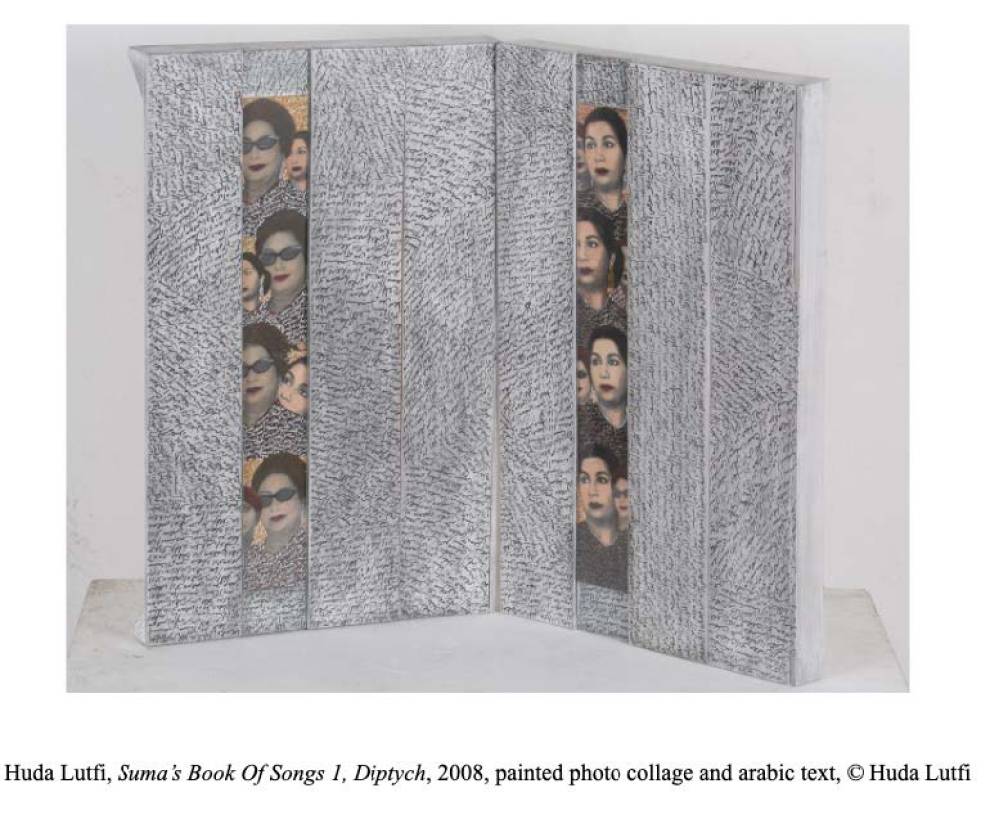

For example, this is Umm El Kulthum, and she's this amazing singer, or Nefertiti, or all these Egyptian icons from cinema or mythology. That was one thing I really loved about her. I felt like she was someone that I wanted to learn from, and she has a profound amount of knowledge, and she studied actual Islamic history and art. So it's not just her own ideas, but is based on things that she is trying to re-tell or add, maybe, to the narrative. Often they come across as quite political. Well, this is political, these are political works. It's not just political for the sake of being political. I think life in Cairo is political for any woman who lives there, for any man, you know. Living in most parts of this region, whatever you do is a political act in some cases.

But then I think in her recent works, she's gone a bit more inwards, but she's still working with collage. She's still working with reappropriating found objects. I like her interest in crafts as well, and sort of referencing it within her work. But Huda is just a gem. I feel like she’s one of these artists that you feel very lucky to have met, and are very honoured to know them and to be part of their life and to participate in getting their message out there.

That's how I felt with Monir. That's how I feel with Huda. And that's how I feel with many of my artists, but I just feel in particular the ones that are older. I guess Huda is now in her mid 70s, she is not super young, she's already been doing this. She's been figuring it out. She's got her language. That's why it's so important that when you look at artists like that, you're looking at a trajectory of work that goes back 4 decades. And maybe Hans Ulrich is right, you need to look at it in a book. Because in a book you can see the chapters and what was happening in their life and the world. For me, all good art is a way to mark time.

I remember during the Arab Spring, Huda was out there, she was going to Tahrir Square. I told her she was to be careful, but she has always had this in her, this idea that people need to know. And collage, like you said, became the best way to speak. Because I think writing is dangerous. So she is basically writing through her images.

JAR:

We've talked a lot about traditional crafts as well as collage and photography, they just seem to be just really powerful mediums for women to use. Somehow they come across initially as accessible and maybe more subtle. Especially through the work of Huda. But it just becomes so powerful.

SH:

It's interesting. I mean, Monir did some collages, too, in her life. And it's true. She made these memory boxes, which translated to heartaches. I feel collage sometimes can create a new world using images from your world. It's world-making. But it could also be like hiding something right? Because you haven’t used the full image, this image is no longer in context of the place or the thing it was a part of.

JAR:

There's one collage of Huda’s, where this reclining woman is cut in half.

SH:

But she's in pieces.

JAR:

It is decontextualising the female form through its aggressive division, placing her body in two different spheres. Her face is even separated from her body. I feel as a woman, especially in Cairo, you feel so torn between yourself and the shame placed on your body. Her work very visually gives her this freedom to express this dichotomy. As you said, writing is so dangerous There's so many women that have been exiled or placed in prison for writing. Collage is just a really important medium.

SH:

There are so many writers that are not able to live in Egypt. And also for collage, perhaps there's a way to hide in that, you know, it's like, well, these are not my images. I didn't make this image. I just took it.

JAR:

You can really tell how immersed she is in her cultural landscape. I love this one work of hers called the The Perfumed Garden. She went to the souks in Cairo and collected these glass bottles, and then found circulated images of either family friends or famous female figures. And literally traps these women in these glass bottles. Visually when you see it, it's so powerful. Embodying this idea of entrapment and domesticity, especially through the rigidness of the piece, Lutfi complicates our understanding of the female experience.

SH:

Like these messages in a bottle. Right? I love that piece, I'm glad you chose that piece, it's a really good work.

Also, she uses texts in her works. They're usually referencing a song. She was telling me about this piece she recently did for the Islamic Arts Biennale. So it's a quote from the Quran. It's about how God is everywhere. And I spoke to her about it. This one particular surah is about if you look in the West, if you look in the East, if you look in the South, God is everywhere. So God is one, and we don't have to be in competition with one another about our relationship. Even that is interesting, how she uses texts and then repeats them over and over in her works as well, and she does song lyrics as well, like Umm El Kulthum with certain verses repeated.

JAR:

It was so hard to pick what to talk about in regard to her work because every time you see another work you want to talk about it. I wanted to talk about her paintings, like the Dawn portraits. And how she uses text, mannequins, and even just using motifs like the Coptic doll. And just so many ancient and mythological references.

SH:

Egypt and Egyptians need Huda Lutfi. These are the voices. This is why art is important, you know. It's not just for our consumption. It's also for our knowledge, it's to know what's happening.

JAR

I think the world needs all of the artists at The Third Line, especially the ones we've talked about. I really hope this conversation shows people that.

SH:

I'm glad we're doing it, and I'm happy to help, and I think it is important. I think people just don't know because they don't read about it enough, like you said, it's not available to them. And they just make their own assumptions, or they compare it to a Western canon. Yes, it can be inspired by or similar to Western artworks. For example, for Monir, this is the time that she was making art, but then she completely took it and changed it to something else. We often get that. But it's okay, because maybe they just haven’t seen enough.

Close

Close