Ελληνικά

under the aegis of the Canadian Institute in Greece and the Hellenic Ministry of Culture

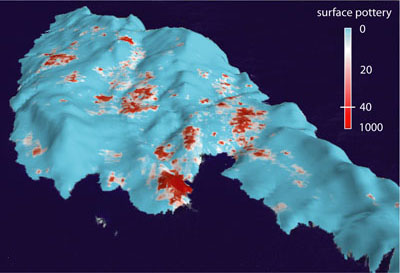

A perspective view of Antikythera, looking south, with a walker-scale plot of surface ceramic density (all periods). Image by A. Bevan.

Delineating the history of human exploitation on Antikythera is a primary research objective for ASP, and we are here able to offer some preliminary observations based on our first phase of study of the survey data.

We are now in a position to offer some preliminary thoughts about the island’s long-term settlement history. The earliest identifiable evidence of human activity on the island dates to the the Late to Final Neolithic (5th to 4th millennium BC), for which we have both diagnostic pro jectile points, and also tiny, concentrated scatters (less than 0.25 ha) of chert and obsidian artifacts. Small amounts of Final Neolithic to Early Bronze I pottery are associated with many of these scatters (with a few knapped stone artefacts suggesting an earlier Late Neolithic phase for which we have not found surface pottery), and we propose that the earliest stages of this activity probably involved non-permanent visitations by hunters from either Crete or Kythera. Migratory birds may have been one resource that such groups were looking to exploit (perhaps by netting) but either native or introduced deer and/or goat are also possible targets and more likely to have been hunted by pro jectile weapons. We suspect an interesting set of relationships between these early sites and their ecological setting -- many are located in places that are easier to traverse, sometimes along likely routeways across the island, sometimes afforded better visibility of the surrounding area and/or access to standing water. Each of these factors requires far greater formal investigation before it can be confirmed, but such a landuse pattern may well extend into the early 3rd millennium BC and is possible that the island was only settled on a permanent basis much later than neighbouring Kythera and western Crete.

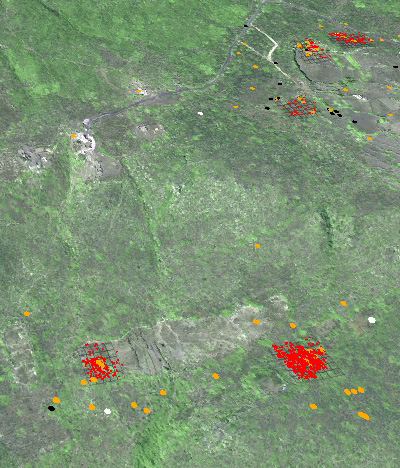

The beginning of a more substantial and differently configured settlement is hard to date without further study, but might begin as early as the Early Bronze Age II period (ca 2900-2200 BC) or immediately thereafter. It certainly seems established by the First Palace period (ca.1900-1750 BC) and continues through the Second and Third Palace periods (traditionally, ca.1750-1450 and 1450-1200 BC). These Minoan and Mycenaean palatial period scatters are larger (typically between 0.25 to 0.5 ha), relatively tightly-focused and compositionally consistent with what might be permanent, single-family farmsteads (with occasional variations that suggests our final explanations eventually may need to be more subtle). We have documented 25 to 30 such scatters, dispersed in looser clusters of two or more discrete scatters each (see figure 5). In all cases, they are found in parts of the island that were more suitable for cultivation and it appears that people involved were exploiting particular soils and topographic features, such as flysch-filled sink-holes or marly, alluvial deposits in shallow channels that could be cross-terraced to aid in soil and moisture retention. Again further analytical work is needed to confirm or reject such suppositions in a more formal way.

The next obvious phase of settlement occurs about a millennium later, most prominently in the Hellenistic period (ca.323-146 BC) when the island is dominated by a fortified town (ca.7 ha) at a strategic position on its northern coast, overlooking the natural protected harbour at Xeropotamos. Documentary evidence refers to the town and island as Aegila and points to its role in piracy. Indeed, the town’s location is not best-placed in terms of the island’s main agricultural areas, but well-positioned for access to the busy Hellenistic shipping lanes running between the Peloponnese and Crete, and east-west between Aegean and central Mediterranean. Our survey indicates the presence of other Hellenistic scatters on the island however and it remains to be seen whether these reflect smaller, more agriculturally-oriented communities or are, in some manner, part of the logistical and economic agenda of the fortified town itself. The latter’s sack by the Romans in ca. 64 BC seems to have prompted a dramatic decline in activity and we do not find evidence for similarly extensive levels of surface finds until much later, in the Late Roman period (ca.5th-7th century AD). By this time, we can document 4-5 denser clusters of material, often accompanied by small groups of contemporary cist graves, each at the heart of a more fertile region of the island. Most of these appear to be relatively small, perhaps several families at most, but the one above the modern town of Potamos (Zampetiana) suggests a larger village-sized cluster. Some Late Roman evidence form the Xeropotamos harbour suggests its continued importance during this period, but the Potamos harbour may have been increasingly important, especially given the suspicion that a combination of tectonic uplift and alluvial build up would have been making the former increasingly difficult to use.

A perspective view of prehistoric scatters near Katsaneviana: prehistoric pottery finds are shown in red (from grid collections) and orange (from tractwalking), with worked fragments of obsidian and chert shown in black and white respectively. The two scatters in the immediate foreground appear to be a pair of small Minoan palatial period farmsteads. Image by A. Bevan.

Further abrupt discontinuity in the island’s settlement pattern is arguably visible in the following two centuries, followed by a period of renewed exploitation by around the 12th century, with some interesting material appearing at a variety of locations across the island. Again, our pottery study is still at a preliminary stage, but the following periods are represented by limited numbers of finds that suggest much lower level activity again (and perhaps little if any permanent settlement) up until the historically documented recolonization of Antikythera in the late 18th century. This last chapter in the island’s history has also been a dramatic one: in community memory at least it seems to have begun with a relatively small colonisation episode by a few families from the Chania region in western Crete, but was sustained and built upon by a period of internal population growth and in-migration over the 19th century, with up to ten different small clusters of houses, mainly called after their founding family’s name. The associated modern pottery is spread very widely over the landscape, but shows interesting functional differentiation, with certain tableware types appearing more commonly in the area immediately around the houses themselves. The population has however declined during the 20th century and dramatically so in the years since World War II, to a winter population of no more than 30 inhabitants. To some extent, we are keen to understand whether the social and economic details of this recent pattern of colonisation, prosperity over a couple of centuries, and decline offer important insights for other apparent demographic fluctuations and land use rhythms in the island’s past or whether they reflect atypical, historically-contingent factors.

It is fair to say that on a larger scale, there are a limited number of more fertile locales on the island that have been exploited repeatedly through time. However, for such a small place, Antikythera still throes up some interesting questions regarding the re-use of various forms of capital investment in the landscape. At smaller scales, important variations in people's subsistence and communication strategies can be identified and more importantly, capital investments in the landscape such as terraces seem to have had a history of re-use that, if our early efforts to understand the chrnology of such activites is anything to go by, cross-cut some apparent phases of abandonment. Likwise, at the scale individual settlement locations or activity areas, we sometimes see evidence of separate phases of activity separated by large expanses of time, suggesting that, certain points in the landscape acquired a stronger sense of place, often with nothing really to differentiate them but, presumably, for the vestiges of past activity.