6 Slovenian Dual

6.1 Basic facts

Slovenian is a language with three number categories: singular, dual, and plural.

| singular | dual | plural | |

| nominative/accusative | mest-o | mest-i | mest-a |

| dative | mest-u | mest-oma | mest-om |

| instrumental | mest-om | mest-oma | mest-i |

| genitive | mest-a | mest-_ | mest-_ |

T-a dv-a stol-a st-a polomljen-a.

these-DU.M.NOM two-DU.M.NOM chair-DU.M.NOM be-3.DU.PRES broken-DU.M.NOM

‘These two chairs are broken.’

(Derganc 2003: p.168)

Two peculiar properties of Slovenian duals

Bare duals in Slovenian tend to receive definite interpretations, unlike bare singulars and bare plurals, which are simply underspecified for definiteness (Jakopin 1966; Dvořák and Sauerland 2006).

Nouns that come naturally in pairs (paired nouns) are usually occur in plural, e.g. roke ‘hands’, noge ‘feet’, oči ‘eyes’, čevlji ‘shoes’, rokavice ‘gloves’, starši ‘parents’ (Derganc 2003 @dvoraksauerland:06; Sauerland 2008).

-

Noge me bolijo.

foot.PL me hurt

‘My feet hurt.’ -

#Nogi me bolija.

foot.DU me hurt

The dual forms of these nouns can be used to describe two entities that are not naturally paired, e.g. nogi can describe my right food and your left foot. Similar contextual effects are observed with Hungarian paired nouns.

Modifiers dva ‘two’ and oba ‘both’ select for dual nouns.

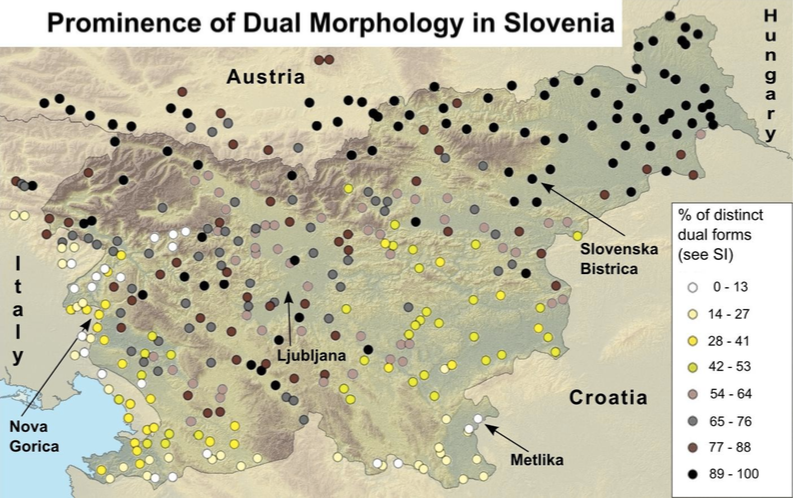

There is a considerable degree of dialectal variation as to which nouns have dual forms. Some southern dialects lack dual nouns altogether.

6.2 Sauerland’s analysis

Extending his view of singular vs. plural in German and English, Sauerland (2008) claims that the Slovenian dual is semantically compatible with singular reference and dual reference (‘one or two’).

As support of this claim he presents the following data.

Vsak študent je prinesel s seboj svoj-i knjig-i.

every student be.SG brought.M *with self his-DL book-DL.

‘Every student brought his books.’

He reports that this sentence is acceptable in a context where some students have one book and the others have exactly two.

6.3 More data

Marušič, Žaucer, Sudo and Nevins (in progress) assessed judgments of sentences like Example 6.3 in three different contexts.- 〔1 or 2〕: Some students have exactly one book, the others have exactly two.

- 〔2 or 3〕: Some students have exactly two books, the others have exactly three.

- 〔exactly 2〕: Every student has exactly two books.

In addition to dual (DL), we tested the versions of the sentences where the noun appears in plural (PL), singular (SG), and with the numeral dva (NUM).

In each trial, the context was introduced in a yes/no-question following the target sentence (e.g. ‘Can one use this sentence in a situation where some students have exactly one book, the others have exactly two?’), and answers were given by ja ‘yes’ or ne ‘no’.

21 speakers of Slovenian dialects that have duals were cruited at the University of Ljubljana.

6.4 Discussion

The results suggest that the semantics of DL is not compatible with singular reference, contrary to Sauerland (2008). Rather, they suggest that DL is semantically compatible with〔2 or 3〕. But the moderate acceptability of this condition needs to be explained.

To this end it’s instructive to look at the results of NUM, which behaved quite similarly. There are several semantic theories of numberals:

- Scalar Strengthening Theory: Numberals are semantically just lower bounded (‘at least’), and get upper bounded readings (‘exactly’) via scalar strengthening with respect to higher numerals. (Horn 1972)

- Lexical Ambiguity Theory: Numerals are lexically ambiguous between lower-bounded and exact readings. (Geurts 2006)

- Pragmatic Weakening Theory: Numerals have exact readings. Pragmatic weakening gives rise to lower-bounded readings. (Breheny 2008)

All these views can be made compatible with the moderate acceptability of NUM in 〔2 or 3〕.

- Scalar Strengthening Theory: In 〔2 or 3〕you have to cancel the scalar inference, which is arguably costly.

- Lexical Ambiguity Theory: It needs to be assumed that the lower bounded reading is somehow less readily accessible, or that the judgments improve when both readings are true.

- Pragmatic Weakening Theory: Pragmatic weakening is an additional process so it can be assumed to incur some cognitive cost and/or is not perfectly motivated in this experimental setting.

Let us extend these views to DL:

- Scalar Strengthening Theory: DL does not seem to have a competitor that means ‘at least 3’. Note that PL seems to be number-neutral. It’s then not so clear why DL is not perfectly accepted in 〔2 or 3〕.

- Lexical Ambiguity Theory: It needs to be assumed that the ‘at least’ reading is somehow less readily accessible than the ‘exact’ reading, that the judgments improve when both readings are true.

- Pragmatic Weakening Theory: Pragmatic weakening is an additional process so it can be assumed to incur some cognitive cost and/or is not perfectly motivated in this experimental setting.

PL is judged as acceptable in 〔1 or 2〕and 〔2 or 3〕 (as in English), but interestingly, it is not as good in 〔exactly 2〕. DL is perfectly acceptable in this condition, suggesting that DL and PL compete: DL is more contentful (‘at least two’ or ‘exactly two’ vs. no meaning), so it wins.

But this casts some doubt on the Lexical Ambiguity Theory, because if DL and PL compete in 〔exactly 2〕, they should do so in 〔2 or 3〕as well. DL is not perfectly good there, but since it is not compeletely rejected, it should make PL somewhat more degraded. Though this is not a very convincing argument, but the explanation under the Pragmatic Weeakning Theory is more straightforward.

The results for SG are quite surprising.