4 Morphological vs. Semantic Markedness

Farkas and De Swart (2010) take issue with Sauerland’s (2003) assumption that singular is semantically contentful while plural is number-neutral.

They argue that it is conceptually more attractive to assume that unmarked forms are number-neutral, because:

- The singular is morphologically less marked than the plural across languages (Greenberg 1963; Corbett 2000; Farkas and De Swart 2010; Bale, Gagnon, and Khanjian 2011a). And in other domains, the morphologically less marked form is also semantically less marked, e.g. gender. étudiant ‘student.masculine’ in French seems to be gender-neutral, while étudiant-e ‘student.feminine’ is strictly about female students.

- In languages with general number, the general number is usually morphologically unmarked.

- Hungarian uses unmarked (‘singular’) nouns in quantity construcitons.

három/sok/mindenféle/egz pár/több {gyerek, *gyerekek}

three/many/all kinds of/a couple of/more {child, children}

(Farkas and De Swart 2010, 10)

Bale, Gagnon, and Khanjian (2011b) side with Sauerland (2003) and argue that in the number domain we have the reverse entailment pattern, where the morphologically unmarked noun (singular) is semantically stronger than the morphologically marked noun (plural), because the plural morphology is interpreted as an augmenting function: it takes singular entities denoted by the unmarked form and creates plural entities.

But this is not really a defense of Sauerland’s view:

- Why is it that the the plural doesn’t mean strictly plural?

- More importantly, the issue is actually about the meaning of the singular, not that of the plural. It needs to be explained why the singular is not number neutral (with perhaps the plural being strictly plural).

4.1 Farkas and De Swart (2010)

Farkas and De Swart (2010) start with the assumption that singular is semantically number neutral. They additionally assume that plural is ambiguous between number neutral and strictly plural meaning.

But we don’t want singular to be number neutral everywhere. To derive the strictly singular meaning, they make use of markedness.

- Semantic markedness: Reference to atomic entities is less semantically marked than reference to plural entities.

- Markedness alignment: Mophologically marked forms should have semantically marked meaning

In addition, they assume that the ambiguty of plural is constrained by the Preference for the Strongest Meaning.

4.1.1 Examples

- A singular noun is number neutral, so compatible with both singular and plural reference, but it being morphologially unmarked, it is only used to mean the unmarked meaning, i.e. singular reference. (Farkas and De Swart formalize this in Bi-Directional Optimality Theory, but I’ll skip these details)

Example 4.2

Daniele wrote a poem.

The strictly singular meaning arises because the plural noun is available in the same grammatical context. If that is not the case, the singular noun receives a neumber neutral reading. This is how Farkas and De Swart explain the Hungarian examples in Example 4.1. Similarly, unmarked nouns in languages like Japanese and Chinese receive number neutral interpretations because there is no morphologically marked competitor.

- The plural is ambiguous between number neutral meaning and strictly plural meaning. Farkas and De Swart postulate a principle stating that the stronger meaning is preferred.

Example 4.3

- Daniele wrote books. strictly plural

- Daniele did not write books. number neutral

4.1.2 Issues

Farkas and De Swart’s (2010) intuitions are nice, but there are some unattractive features in their analysis.

1. Plural is assumed to be lexically ambiguous.

- The strictly plural reading drives the competition between singular and plural and derives the singular reading.

- The number neutral reading is purported to account for ‘unmarked plurals’.

If possible, we also want to derive the meaning of the plural as well, rather than just stipulate it.

2. This account of unmarked plurals is not so sophisticated. In particular it fails to account for Spector’s (2007) observation about non-monotonic environments, as Farkas and De Swart themselves concede.Exactly one of my students speaks non-European languages.

Here the two meanings are logically independent from each other, so the Principle of Stronger Meaning fails to favor one meaning over the other. Furthermore neither of the readings corresponds to the meaning we are interested in.

- Strictly plural: One student speaks more than one non-European language and the other students don’t speak more than one non-European language.

- Number neutral: One student speaks at least one non-European language and the other students don’t speak any non-European language.

4.2 Some thoughts on semantic markedness

But is it really conceptually unattractive that the unmarked form ‘entails’ the marked form?

Certainly the opposite entailment pattern is often observed in other domains like gender. But why should we base our theory of semantic markedness solely on entailment?

In particular, notice that under the number neutral semantics for the plural, the denotation of a plural noun contains more information than the denotation of a singular noun.- 〖cup〗= λx. x is a singular cup

- 〖cups〗= λx. x is a singular cup or a plurality consisting of cups

If you look at the extention of “cups”, you know which entities should constitute the denotation of “cup”, namely, the singular ones.

So, the singular only tells you what counts as atomic, while the plural also tells you how to combine them. Then perhaps it’s not so conceptually weird to say that the morphologically marked form carries more information.

Why does it work differently for gender?

- Gender morphology, when it has natural gender interpretation, encodes a way to pick out a particular subset of entities, so the marked form designate the subset of entities.

- Number morphology is not about picking out a subset, but encodes what counts as one and what counts as more than one.

- There is rope on the table. mass

- There is a rope on the table. count

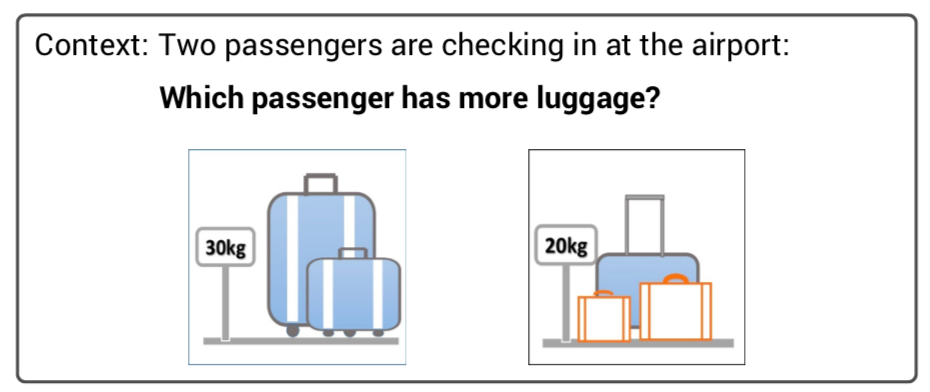

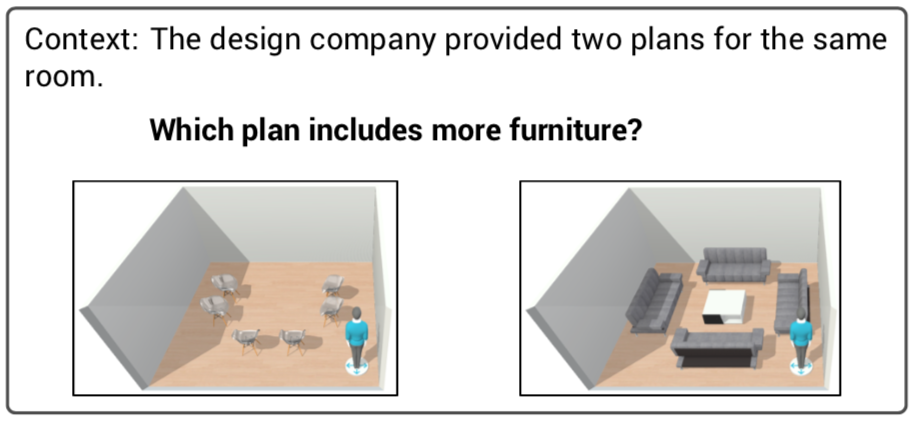

This mass/count distinction is not just a morphosyntactic distinction but has interpretive effects. These effects are clearly observed in Barner and Snedeker’s (2005) comparative task.

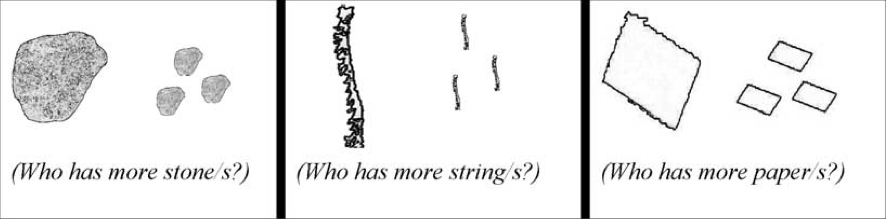

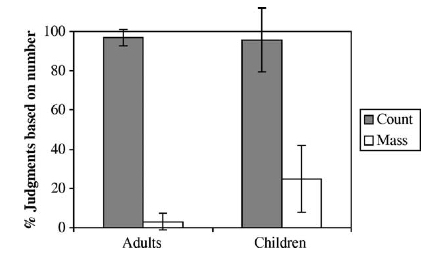

They compared mass and count versions of hybrid nouns.

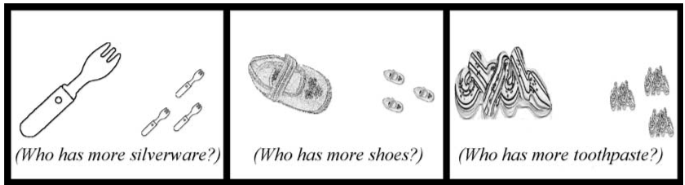

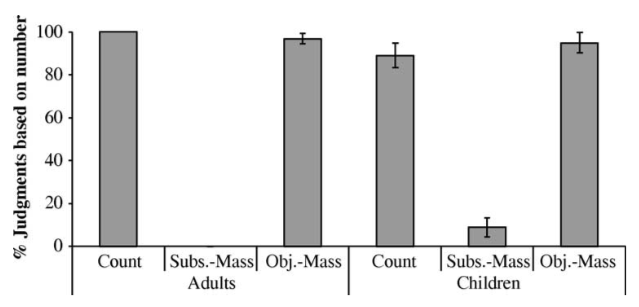

Barner and Snedeker (2005) also looked at mostly count nouns and mostly mass nouns. Among mostly mass nouns, there are those that describe uncountable substances (‘pure mass nouns’) and those that describe discrete objects (‘object mass nouns’).

These results are taken as evidence that object mass nouns have the same kind of semantics (Bale and Barner 2009; see also Chierchia 1998). However, when we look closely there are differences between object mass nouns and count nouns, namely, object mass nouns allow non-count-based interpretations in appropriate contexts, while count nouns really don’t like them.

We ran a similar experiment with contextual bias towards a non-count-based interpretation.

We also contrasted object mass nouns and corresponding count nouns.

- Object mass nouns: software, livestock, furniture, luggage, change, bread, carpeting, sushi

- Count nouns: applications, animals, pieces of furniture, suitcases, coins, slices of bread, carpets, pieces of suchi

The results indicate that non-count-based interpretations are far easier with object mass nouns.

From this we can conjecture:

- Mass nouns encode no countability information. Their denotations should be represented as such.

- ‘Singular’ count nouns encodes countability (although it is not signaled by nominal morphology). The minimal thing that is encoded is the information about what counts as one, so their denotations can be represented as a set of atomic elements (with respect to the noun).

- ‘Plural’ count nouns simultaneously contains the information about what counts as one and the information about how to combine plural entities.

Given that number morphosyntax is not about marking a subset of entities, it doesn’t care much about the entailment/subset pattern.

Admittedly, there are certain things that are not explained:

Why doesn’t English use nominal morphology to differentiate singular count nouns from mass nouns? In fact there aren’t many languages that do this. Lena Spanish is said to mark mass nouns, but the relevant morphology is not productive (Corbett 2000: p.124) and the data are not qualitatively different from meubel-meubels-meubilair ‘furniture’ in Dutch. There are also languages that use other morphology, e.g. a diminutive suffix, a gender suffix, to differentiate a mass noun and its count singular noun, but there seems to be no language that has a dedicated number marking that distinguishes mass vs. singular count.

Why is it that English has no nominal morphology that marks strict plurality?