There is no system for collection or processing of compostable plastic in the UK. Government must develop plans for dealing with this growing waste stream.

Use of compostable plastics

The environmental impact of plastic waste has caused recent public outcry. This has created a mandate for wholesale change in the use of plastics in packaging.

The UK Plastics Pact was launched in April 2018. It is a coalition of more than 120 businesses, governments, local authorities and organisations committed to tackling plastic pollution. Members have signed up to a target to “make all plastic packaging 100% recyclable, reusable, or compostable, and to eliminate all unnecessary single-use packaging by 2025”.1

The global market for biodegradable plastics (of which compostable plastics are a subset – see glossary) was 2.11 million tonnes in 2018 and is set to grow to 2.62 million tonnes by 2023.2 For comparison, 335 million tonnes of plastic are produced annually.3

Although compostable plastics are often presented as a sustainable solution to the plastic waste problem, these claims are largely unsubstantiated and have led to widespread confusion among consumers about:

- how they should dispose of these products;

- what terms such as “bioplastic”, “biodegradable”, and “compostable” mean; and

- whether these new products are safe for the environment.

Missing the point

At present, there is no UK-wide system for the collection and processing of compostable plastics.

If compostable plastics are introduced into recycling streams, they contaminate them and reduce the quality (and therefore value) of the recycled plastics produced.

Some industrial processing of food waste requires different conditions to those required for compostable plastics. Anaerobic Digestion (AD) plants for food use screening systems to remove any possible contaminants, including biodegradable plastics. However, In Vessel Composting (IVC) for food waste can treat compostable plastics.

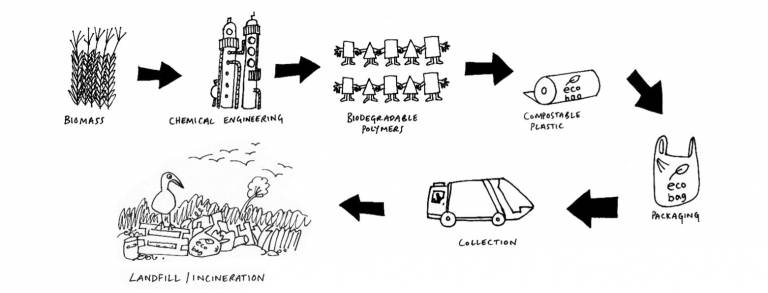

Figure 1: The current life cycle of most compostable plastics

If compostable plastics end up in the environment, their fate is less certain. Most compostable plastics will not degrade to any significant extent in the sea or in cold, dry environments. Compostable plastics that end up in rivers or the sea are likely to be there for many years.

While the temperature and oxygen levels within an industrial composter can be carefully managed, conditions within home composting (such as compost heaps and compost bins) are much more varied. There is very little data about how well compostable plastics break down under home composting conditions. Our BIG COMPOST EXPERIMENT aims to fill this gap.4

Therefore, within the UK, the best waste stream for compostable plastics is currently the general waste, through which they will be sent to landfill or burnt. While the plant-based nature of the plastics can in some cases offer a small environmental benefit over petroleum-derived plastics5, there is no additional benefit to be gained from the fact that they are compostable if they are not ultimately composted. In fact, they may have a detrimental impact if they contaminate recyclable plastics, end up as litter or displace reusable or recyclable alternatives.

Standards, labels and regulation

There are well-established European standards for industrial composting of plastics, as well as associated labelling schemes that identify whether they meet these standards. There is no standard for home composting, but some certifications exist, including UNI 11183 (Italy), AS 5810 (Australia), NT T 51-800 (France) and OK Compost (Belgium).

In the UK, the Association for Organics Recycling operates a certification scheme in partnership with Germany’s DIN-CERTCO scheme, which aligns with the requirements of the EU standard for compostable and biodegradable packaging.6

Compostable plastics do not currently have to be registered under regulation for chemicals. As a result, little is known about the potential impact of additives that are used to accelerate the breakdown process. Tougher regulation may be necessary to ensure that they do not pose a threat to the environment, food chains or to the plastic recycling waste stream.

Establishing a sustainable compostable plastics system

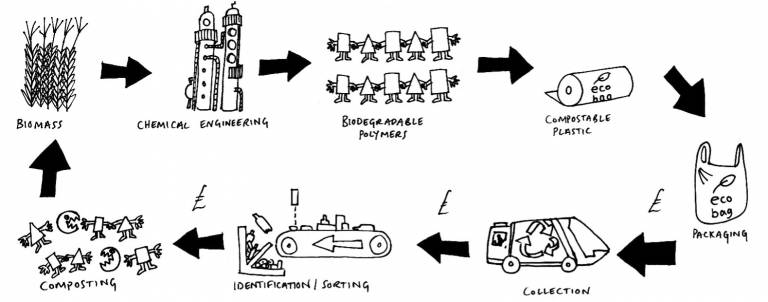

A sustainable system would see compostable plastics properly composted and used again in agriculture or gardens (see Fig. 2) creating a circular economy. However, there are some significant barriers to this.

Collection

There is currently no household collection service for compostable plastics. The most viable option would be to modify food waste collection and composting to accommodate compostable plastics used in food and drink packaging.

Sorting and separating compostable plastics

A sustainable system for compostable plastics would need a method for reliably sorting and separating compostable plastics from other plastics and/or from food waste (depending on the product type and processing route). This does not currently exist and would need further research and development to be implemented.

Most industrial composting plants use mechanical screening systems to remove any possible contaminants, including plastics. These systems are not able to differentiate between compostable and non-compostable plastics (due to their similar weights, densities and visual appearance).

Technologies do exist that could be used for mechanical sorting. These include near-infrared technology (that can detect different types and grades of plastics) and image recognition, where machines identify items of packaging through marker technologies attached to each item.7

Economics

For compostable plastics to form part of a circular economy, the additional costs of collecting, sorting and composting them need to be covered. The UK has had a system of producer responsibility for packaging since 1997, which is intended to place the costs of recycling packaging waste on producers. Companies over a certain size must meet these obligations by purchasing Packaging Waste Recovery Notes (PRNs) or Packaging Waste Export Recovery Notes (PERNs) from accredited processors and exporters as proof of compliance. However, in practice, the scheme has not delivered on the goal of making the “polluter pay” and taxpayers still cover the vast majority of the costs of packaging waste disposal.8

The Government is planning to reform the current system so that producers fund the management of packaging at the end of its life.9 This provides an opportunity to create a source of funding for a system of managing compostable plastics.

One option could be to create a fund from the PRN system by setting a minimum price for PRNs and ring fencing some of this money for investment in a compostable plastics collection and composting system.

Behaviour change

Currently, there is little public awareness that specialised collection and processing is necessary for compostable plastics. People might understandably, but wrongly, assume that items labelled as compostable can be put into food waste or recycling.

Similarly, people may incorrectly assume that “biodegradable” items will rot down in any environment, leading to pollution and littering. For example, “biodegradable” wipes that are flushed down toilets can block sewers or end up in the sea.

Awareness will need to be improved to fully realise the benefits of compostable plastics.

Uses for compostable plastics

Compostable plastics offer a clear benefit where they are replacing plastic products that cannot be recycled and which would otherwise end up in landfill or an incinerator. One such category is products that are contaminated, such as nappies, wipes and feminine hygiene products. Liners for food waste caddies and tea bags are another area.

Another possible area of application is single-use food packaging, where contamination by the food is likely. The benefits here are less clear cut; if people can be persuaded to wash the packaging, it might be possible to recycle it through the existing plastic recycling system.

Funders

The Plastic Waste Innovation Hub has been fully funded through a UKRI/EPSRC PRIF grant (EP/SO24883/1).

About the authors

The authors of this briefing are a multidisciplinary group of academics including scientists, engineers, designers, artists and social scientists from UCL’s Plastic Waste Innovation Hub:

Dr Teresa Domenech Aparsi, Charnett Chau, Dr Kimberley Chandler, Dr Dragana Dobrijevic, Prof Helen Hailes, Lewis Hall, Dr Leona Leipold, Prof Paola Lettieri, Nancy Lu, Prof Francesca Medda, Prof Susan Michie, Prof Mark Miodownik, Dr Candace Partridge, Danielle Purkiss, Prof John Ward, and Ruby Wright.

The Plastic Waste Innovation Hub is led by Professor Mark Miodownik. Further information is available at: www.plasticwastehub.org.uk

Next steps

We will soon commence a new three-year research project, funded by the Natural Environment Research Council, to investigate how barriers to creating a circular economy of compostable plastics might be overcome.

Contact: hello@plasticwastehub.org.uk

References and further reading

- WRAP (2018) The UK Plastics Pact

- European Bioplastics (2018) Bioplastics Market Data available at: www.european-bioplastics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Report_Bioplastics-Market-Data_2018.pdf

- Ibid

- UCL Big Compost Experiment: www.bigcompostexperiment.org.uk

- Spierling, S., Knüpffer, E., Behnsen, H., Mudersbach, M., Krieg, H., Springer, S., Albrecht, S., Herrmann, C., & Endres, H. J. (2018). Bio-based plastics - A review of environmental, social and economic impact assessments.Journal of Cleaner Production, 185, 476–491. ; Yates, M. R., & Barlow, C. Y. (2013). Life cycle assessments of biodegradable, commercial biopolymers - A critical review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 78, 54–66.

- British Plastics Foundation (2019) Packaging waste directive and standards for compostability

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2016) The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics

- Environmental Audit Committee (2017) Plastic bottles: Turning Back the Plastic Tide

- Defra and Environment Agency (2018) Resources and waste strategy for England ; Defra, Environment Bill 2020

- Heidbreder, L. et al (2019) Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviours, and interventions, Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 668, pp. 1077-1093

- Chau, C., Lu, N., Hall, L. and Lettieri, P. Life cycle assessments comparing replacing petroleum-based plastics with biodegradable plastics in two products: tree shelters & feminine hygiene pads (In preparation.)

- Partridge, C. and Medda, F. (2019) ‘Opportunities for chemical recycling to benefit from waste policy changes in the United Kingdom’, Resources, Conservation & Recycling, Vol. 3

- WRAP and The UK Plastics Pact (2018) ‘Understanding plastic packaging and the language we use to describe it’

- WRAP (2020) Compostable plastic packaging guidance

November 2020

Close

Close