The Multimodal Language Corpora Workshop brought together researchers sharing a strong interest in communication and conversation in real-world settings.

Researchers from psychology, cognitive neuroscience, linguistics and computer science working on multimodal corpora explored questions related to social interaction, language development, language production, comprehension, linguistic structure and use.

Together, we aimed to:

- Raise awareness of the wealth of different corpora that have been developed;

- Allow participants to share good practice and work toward better ways to deal with key issues;

- Identify opportunities for collaboration cross-corpora;

- Assess interest and scope for developing shared resources or other ways to bring the conversation forward.

The 2023 MLC Workshop established a network of researchers interested in multimodal language corpora. The second MLC Workshop will take place in Marseille in 2024. Interested? Get in touch!

Reflections

The workshop highlighted the importance of maintaining a network of researchers working on multimodal corpora of spoken and sign languages. Sharing lessons learned with each other allows us to not repeat mistakes in annotation, tools, and/or processes.

- Annotation

- Share your annotation manual with other researchers. This maintains transparency and means that nobody needs to reinvent the wheel.

- Ensuring consistency across annotation systems at top-level allows for comprehension, replication and extension.

- Annotation systems are bound to differ, especially regarding the level of detail with which you annotate your data. This is not necessarily a bad thing, if decisions are well-justified.

- Tools

- Automated annotation tools (e.g., OpenFace, Whisper) involve a trade off: they work much better for some behaviours (eg. speech transcription) than others (gestures/facial expressions). Sometimes it can be more work to use them than doing manual annotation.

- If you plan to use automated tools, make sure you are 1) collecting high-quality video and audio data and 2) check reliability against manual annotation. There may be value to manual annotation in getting to know your data

- Process

- Check which corpora already exist before collecting your own.

- Think about ethical considerations before you collect the corpus. Some things (e.g., the right to be forgotten) can be difficult to enforce in hindsight.

- Consider ethics and protections across all regions that are relevant to your corpus (e.g. UK GDPR, USA Privacy Act).

- Consider multiple forms of consent and think about consent beyond legal status (e.g., ‘assent’ from children and young people).

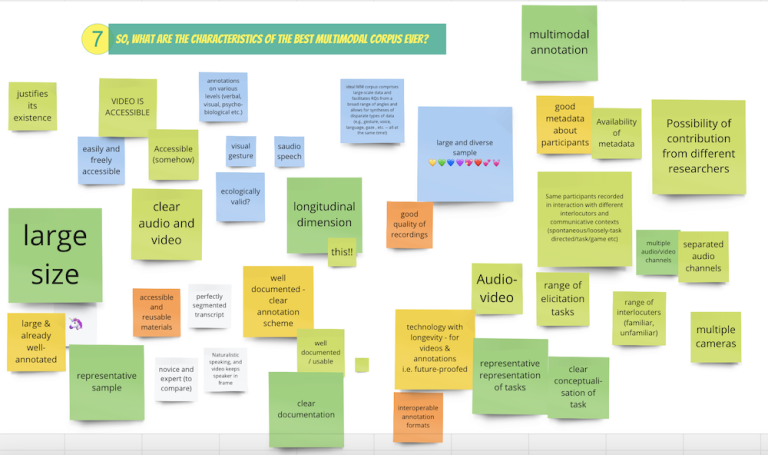

The Ideal Corpus

We closed the workshop by considering the "ideal" multimodal language corpus. For our participants, the ideal corpus ...

- ... includes a diverse and large sample

- ... has a well-documented and clear annotation scheme

- ... has high-quality audio or video recordings

- ... is the result of well-justified decisions

- ... is accessible to researchers and advertised across communities

Featured Corpora

The corpora presented differed along many dimensions, including size, availability, characteristics of the people (and how many) being recorded, the language spoken/signed, the “task”, and what has been annotated. Together, they exemplify a good range of the typical real-world scenarios in which we use multimodal language.

- The British Sign Language Corpus

Presented by Kearsy Cormier, UCL

The British Sign Language (BSL) Corpus is the first corpus of its kind in the United Kingdom (i.e., a large machine-readable open access dataset that is maximally representative of the language) and one of the largest sign language corpora in the world. It comprises 249 deaf BSL signers (native signers or early learners) from 8 regions across the UK: Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, London, Manchester and Newcastle. Within each region, participants were mixed as much as possible for age, gender, language background (deaf or hearing family), ethnicity and socioeconomic class. They were filmed in pairs taking part in in four tasks: personal narrative, free conversation, a lexical elicitation task, and an interview. The video data (around 125 hours total) were filmed and archived between 2008 and 2011 (Schembri et al., 2013, 2014).

Accessibility: The Data page on the BSL Corpus website provides two options for viewing and browsing. One is a deaf-friendly part of the site that allows users to drill down, selecting region then a subset of tasks then age group to see a select group of videos that meets those criteria, aimed at general public. The other is CAVA aimed more at researchers, teachers, students– where videos and ID gloss/translation annotations of two of the tasks (narrative and lexical elicitation) are openly available for anyone to view and download. The other two tasks (conversation and interview) are available to registered researchers upon signing a confidentiality agreement (Schembri et al., 2013).

Annotations and linguistic studies: Annotations using ELAN began in 2011 and have been ongoing since. Annotations include: English translations of all narratives, 70,000 ID gloss (lexical level – linked to the lexical database BSL Signbank) annotations and English translations from some conversations and some narratives – all of which are publicly available to registered researchers on UCL CAVA in addition to annotation conventions that describe the existing ID gloss and translation annotations. There is also a large number of additional tiers not publicly available that have been created as part of particular studies including linguistic structure - handshape variation (Fenlon et al., 2013), lexical frequency (Fenlon et al., 2014), lexical variation (Stamp et al., 2014), fingerspelling (Brown & Cormier, 2017), verb directionality (Fenlon et al., 2018), mouthing (Proctor & Cormier, 2022), and various syntactic structures (Hodge et al., in prep) – as well as language attitudes (Rowley & Cormier, 2021, 2023). Given its open accesibility, the BSL Corpus has also been used by researchers outside of UCL (e.g. Caudrelier 2014; Davidson, 2017; Green & Eshghi, 2023).

Applications: In addition to linguistic research, the BSL Corpus has also been used for teaching and learning BSL and interpreting. It is also used for machine learning purposes, to train and test systems being developed for automatic translation between BSL and English (Cormier et al., 2019). This is also resulting in tools to automate and speed up annotation for linguistic purposes (e.g. Jiang et al., 2021; Woll et al., 2022) – which is highly desired by sign linguists given the very slow process of human annotation. It is likely that many automated tools useful for sign language researchers may also be useful for multimodal language researchers – this will be one topic for discussion.

Brown, M., & Cormier, K. (2017). Sociolinguistic variation in the nativisation of BSL fingerspelling. Open Linguistics, 3(1), 115-144. Caudrelier, G. (2014). The Syntax of British Sign Language: an Overview, University of Central Lancashire. Masters thesis. Cormier, K., Fox, N., Woll, B., Zisserman, A., Camgoz, N. C., & Bowden, R. (2019). ExTOL: Automatic recognition of British Sign Language using the BSL Corpus. 6th Workshop on Sign Language Translation and Avatar Technology, Hamburg, Germany. Davidson, L. (2017). Personal experience narratives in the deaf community: Identifying deaf-world typicality, University of Central Lancashire. Masters thesis. Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., Rentelis, R., & Cormier, K. (2013). Variation in handshape and orientation in British Sign Language: The case of the '1' hand configuration. Language and Communication, 33, 69-91. Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., Rentelis, R., Vinson, D., & Cormier, K. (2014). Using conversational data to determine lexical frequency in British Sign Language: The influence of text type. Lingua, 143, 187-202. Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., & Cormier, K. (2018). Modification of indicating verbs in British Sign Language: A corpus-based study. Language, 94(1), 84-118. Green, D., & Eshghi, A. (2023, 16-17 August 2023). One Signer at a Time? A Corpus Study of Turn-Taking Patterns in Signed Dialogue. Workshop on the Semantics and Pragmatics of Dialogue (SemDial), University of Maribor, Slovenia. Jiang, T., Camgoz, N. C., & Bowden, R. (2021). Looking for the Signs: Identifying Isolated Sign Instances in Continuous Video Footage. 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021), 1-8. Proctor, H., & Cormier, K. (2022). Sociolinguistic Variation in Mouthings in British Sign Language (BSL): A Corpus-Based Study. Language and Speech, 1-30. Rowley, K., & Cormier, K. (2021). Accent or not? Language attitudes towards regional variation in British Sign Language. Applied Linguistics Review. Rowley, K., & Cormier, K. (2023). Attitudes Towards Age Variation and Language Change in the British Deaf Community. Language and Communication, 92, 15-32. Schembri, A., Fenlon, J., Rentelis, R., Reynolds, S., & Cormier, K. (2013). Building the British Sign Language Corpus. Language Documentation and Conservation, 7, 136-154. Schembri, A., Fenlon, J., Rentelis, R., & Cormier, K. (2014). British Sign Language Corpus Project: A corpus of digital video data and annotations of British Sign Language 2008-2014 (Second Edition). University College London. http://www.bslcorpusproject.org. Stamp, R., Schembri, A., Fenlon, J., Rentelis, R., Woll, B., & Cormier, K. (2014). Lexical variation and change in British Sign Language. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e94053. Woll, B., Fox, N., & Cormier, K. (2022). Segmentation of Signs for Research Purposes: Comparing Humans and Machines. LREC 2022. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2022/workshops/signlang/2022.si...

- Conversation: A Naturalistic Dataset of Online Recordings (CANDOR) Corpus

Presented by Gus Cooney, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

CANDOR is a large, novel, and multimodal corpus of 1656 conversations recorded in spoken English. This 7+ million word, 850-hour corpus totals more than 1 terabyte of audio, video, and transcripts, with moment-to-moment measures of vocal, facial, and semantic expression, together with an extensive survey of speakers’ post-conversation reflections.

Over the course of 2020, we matched a large sample of American adults to have dyadic conversations using online video chat. To our knowledge, it is among the largest multimodal datasets of naturally occurring conversation, containing (1) full text, audio, and video records; (2) an extensive battery of post-conversation reflections and assessments; and (3) fine-grained, algorithmically extracted features related to emotion, sentiment, and behavior. Notably, the corpus also offers a unique lens into a period of societal upheaval that includes the start of the pandemic and a hotly contested US Presidential election.

By taking advantage of the considerable scope of the corpus, we explore in an accompanying publication many examples of how this large-scale public dataset may catalyze future research, particularly across disciplinary boundaries, as scholars from a variety of fields appear increasingly interested in the study of conversation.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adf3197

In our report, we present results in four broad categories.

- We leverage the considerable scope and diversity of the corpus to replicate and extend key findings from several literatures—including the cooperativeness of turn-taking and the impacts of conversation on psychological well-being.

- We apply machine-learning models to every second of interaction, to quantify conversation dynamics at scale, and identify semantic, auditory, and visual behaviors that distinguish successful conversationalists.

- We develop algorithmic procedures for segmenting speech into conversational turns and demonstrate how results hinge critically on the choice of context-appropriate algorithms.

Finally, we conduct a rich, mixed-methods analysis of the topical, relational, and demographic diversity of our corpus: we analyze how the national discourse shifted over a tumultuous year, qualitatively review the corpus to identify new concepts like depth of rapport; and quantitatively examine how people alter their speech, listening patterns, and facial expressions when talking to partners from diverse backgrounds and identity groups.

Ultimately, the results we present only scratch the surface of the corpus. Indeed, we regard our findings as an initial pass in a much larger endeavor that will require the efforts of many research teams across the social and computational sciences. We hope the release of this large public dataset will foster empirical progress and interdisciplinary collaboration, which is very much needed to advance the study of conversation.

- Chinese Sign Language Shanghai Corpus

Hao Lin, Shanghai International Studies University

Key words: CSL, corpus, frequency

China boasts of 20 million deaf people. The accurate number of Chinese Sign Language (CSL) users is unclear, but it is known that CSL consists of many variants/dialects. Shanghai CSL is a key variant that has played key roles in shaping CSL in its early development (Lin, 2021). The local deaf community has been stable for over 100 years and is still one of the few strongholds of CSL. As there is no public-available CSL corpus yet, we are building an open-accessed, machine-readable, research and social relevant Chinese Sign Language (Shanghai) corpus (Corpus CSL Shanghai). The corpus is the first to document Chinese deaf signers’ life stories, and their natural use of the Shanghai CSL. This paper gives an overview and progress report of the project.

The overarching goals of our project are three folds: (1) Documenting Shanghai CSL at different times; (2) Developing online dictionary; (3) Building up a sustainable platform for CSL research, both synchronically and diachronically (e.g., inter-generational variations).

Our team has collected a corpus of narrative and spontaneous conversations, with topics ranging from their schooling, health, travelling, etc since 2015. So far, 110 deaf signers (age from 20 to 98) have participated in the project, which amounts to about 60-hour video archive. All participants are local Shanghai deaf people. The glosses and Mandarin translations of signs are being coded through ELAN (Lausberg & Sloetjes, 2009) by deaf experts.

Despite the shortage of funding and human resources from time to time, we will review the following outcomes: First, we have finished about 30% of the basic annotations for conversations and about 40% for narratives. We have identified 8899 sign types out of 96478 sign tokens. We divided the sign tokens into two main categories: full-fledged lexicalized signs and non-signs. The latter includes several types that cannot be regarded as sign words: gesture, finger-spelling, classifiers and others. The former is roughly labelled with Part of Speech(PoS) including noun, verb, adjective, adverb, number, name, pronoun and functional signs. Functional signs refer to the words mainly functioning at the level of grammar, lacking concrete meanings. The followings are included: negators(like no, not, not-have), WH question signs, quantifiers (like some, all), particles, which often function like discourse markers, like forget-it, or polar question markers, like good-bad. The reason we put them into covering category functional signs is that their meanings are elusive and they do not fit in any other main categories.

Second, based on part of our corpus data, we have developed the first version of an online Shanghai CSL dictionary Isigner (https://isigner.app/), which offers both IOS and android apps. It consists of 4318 independent lemmas with some lexical information, including basic phonological information, parts of speech, etc. Examples are even offered for a small portion of entries. Third, the corpus provides rich materials for research. For example, we have studied temporal expressions, timelines and number representations in CSL (Lin et al., 2021; Lin & Gu, 2022). (500 words)

- CoCoDev

Abdellah Fourtassi, on behalf of the CoCoDev team, Aix-Marseille University

Existing studies of naturally occurring multimodal conversation have primarily focused on the two ends of the developmental spectrum, i.e., early childhood and adulthood. This leaves a gap in our knowledge about how development unfolds, especially across middle childhood. Our aim is to contribute to filling this gap.

Participants. The target sample is N = 40 dyads, involving three groups of children aged 7, 9, and 11 years old as well as adult-adult dyads. All participants have French as their native language. The data collection is still ongoing; half the target sample (equally balanced across age groups and gender) was collected and fully processed.

Design. Each dyad was recorded at home playing a loosely structured word-guessing game. Dyads were recorded twice: Once in a face-to-face setting and once using computer-mediated video calls. The recordings were carried a few days apart from each other. For the face-to-face settings, we used a mobile eye-tracking (and head motion detection) device that looks/feels like eyeglasses (from Pupil Labs). For the video call recording, the caregiver and child used different computers and communicated from different rooms at home.

Annotation. We attempted to make full use of automatic tools in speech processing and computer vision, although manual annotation/checking was still necessary. For instance, automatic transcription (using Whisper) was generally high-quality and included timestamps at the segment (turn-like) unit as well as the word level. The transcription was then corrected by hand. Models of diarization (I.e., detecting who is speaking and when) were not as good, and the task had to be done entirely by hand. For the non-verbal signals, we focused on the annotation of “gazing at the interlocutor” vs. “averting gaze.” In the case of face-to-face, the face of the interlocutor was automatically detected from the egocentric video (using RetinaFace), and then gaze coordinate data (from the eye-tracking) were used to determine when gaze fixations intersected with the face. Manual checking confirmed the accuracy of this method. For video calls, we automatically extracted gaze data (using OpenFace) and then trained a computer vision algorithm to categorize it into gazing vs. aversion. However, the outcome of this categorization was not satisfactory, so we completed the task using manual annotation.

Potential uses and availability of corpus. To demonstrate the richness of this corpus for the study of child communicative development, we will show preliminary analyses comparing several measures of child-caregiver conversational dynamics across developmental age (7, 9, and 11 years old), modality (verbal vs. non-verbal), and communicative medium (face-to-face vs. video calls). Private access to raw videos could be possible by other researchers via means that are compliant with GDPR and the local regulations of the country.

- ECOLANG

Yan Gu (Experimental Psychology, University College London; Department of Psychology, University of Essex), Ed Donnellan (Experimental Psychology, University College London); Beata Grzyb (Experimental Psychology, University College London), Gwen Brekelmans (Department of Biological and Experimental Psychology, Queen Mary University of London), Margherita Murgiano (Experimental Psychology, University College London), Ricarda Brieke (Experimental Psychology, University College London), Pamela Perniss (Department of Rehabilitation and Special Education, University of Cologne) & Gabriella Vigliocco (Experimental Psychology, University College London)

Communication comprises a wealth of multimodal signals (e.g., gestures, eyegaze, intonation) in addition to speech and there is growing interest in the study of multimodal language.

The ECOLANG corpus provides audiovisual recordings (about 25 mins each) and annotation of multimodal behaviours (speech transcription, gesture, object manipulation, and eye gaze) by British and US English-speaking adults engaged in semi-naturalistic conversation with their child (N = 38, children 3-4 years old) or a familiar adult (N = 32). When deciding how to go about collecting the corpus, we made several decisions. First, we wanted the corpus to be relevant to researchers working on development in children as well as researchers working on language procesing in adults. Hence, we collected both dyadic communication between a caregiver and their child and between two familiar adults, thus introducing a manipulation of the type of addressee. As the two parts of the corpus (adult-child and adult-adult) were collected in relatively comparable conditions, this manipulation allows for the comparison between adults’ multimodal communication with children vs other adults. Second, we wanted the corpus to capture the real-world intertwining of episodes in which the conversants talk about something they both know, and cases in which one of the conversant is more knowledgeable. This is the typical situation studied in language acquisition where the caregiver is more knowledgeable than the child, but it is also a relatively common situation in adult social interactions (e.g., university or just simply when another person teaches us something new). In the corpus, dyads talk about objects that we provide them and we manipulated object familiarity (i.e., whether the object talked about was familiar or unfamiliar to the interlocutor). Cases in which the addressee (child/adult) is unfamiliar with the object and its label provide learning opportunities, thus we can characterise how speakers use multimodal signals when teaching a new concept/label to a child or an adult. Finally, we asked speakers to talk about the objects when these were physically present (situated) or absent (displaced). This manipulation captures the observation that a large part of human communication is about objects and events absent from the physical setting34. Indeed, displacement, i.e., language’s ability to refer to what is not here now, has long been considered as one of the design features of language35. However, we know very little about whether and how speakers modulate their multimodal language based on displacement. Figure 1 provides a schematic of the corpus design.

For each speaker, the speech has been transcribed (automatically and manually) and segmented into utterances. For each utterance, we annotated the topic (the object talked about), and whether the name of the object was produced. Manual behaviours have been annotated manually as: representational, pointing, beat and pragmatic gestures and object manipulations. Speakers’ eyegaze to objects has also been annotated.

Thus, ECOLANG characterises the use of multimodal signals in social interaction and their modulations depending upon the age of the addressee (child or adult); whether the addressee is learning new concepts/words (unfamiliar or familiar objects) and whether they can see and manipulate (present or absent) the objects. It provides ecologically-valid data about the distribution and cooccurrence of the multimodal signals for cognitive scientists and neuroscientists to address questions about real-world language learning and processing; and for computer scientists to develop more human-like artificial agents.

- Freiburg Multimodal Interaction Corpus (FreMIC)

Christoph Ruehlemann, University of Freiburg

Most corpora tacitly subscribe to a speech-only view filtering out anything that is not a ‘word’ and transcribing the spoken language merely orthographically despite the fact that the monomodal view on language is fundamentally incomplete due to the deep intertwining of the verbal, vocal, and kinesic modalities.

This paper introduces the Freiburg Multimodal Interaction Corpus (FreMIC), a multimodal and interactional corpus of unscripted conversation in English currently under construction. At the time of writing, FreMIC comprises (i) c. 29 hrs of video-recordings transcribed and annotated in detail and (ii) automatically (and manually) generated multimodal data.

All conversations are transcribed in ELAN both orthographically and using Jeffersonian conventions to render verbal content and interactionally relevant details of sequencing (e.g., overlap, latching), temporal aspects (pauses, acceleration/deceleration), phonological aspects (e.g., intensity, pitch, stretching, truncation, voice quality), and laughter. Moreover, the orthographic transcriptions are exhaustively PoS-tagged using the CLAWS web tagger (Garside & Smith 1997). ELAN-based transcriptions also provide exhaustive annotations of reenactments (also referred to as (free) direct speech, constructed dialogue, etc.) as well as silent gestures (meaningful gestures that occur without accompanying speech).

The multimodal data are derived from psychophysiological measurements and eyetracking. The psychophysiological measurements include, inter alia, electrodermal activity (EDA, or GSR), which is indicative of emotional arousal. Eyetracking produces data of two kinds: gaze direction and pupil size. In FreMIC, gazes are automatically recorded using the Area-of Interest (AOI) technology. Gaze direction is interactionally key, for example, in turn-taking and reenactments, while changes in pupil size provide a window onto cognitive intensity.

To demonstrate what opportunities FreMIC’s (combination of) transcriptions, annotations, and multmodal data opens up for research in Interactional (Corpus) Linguistics, this paper reports on a study on pupillary responses in selected vs. not-selected recipients of questions. The results show that pupils in selected recipients dilate whereas pupils in not-selected recipients contract . We take this finding as evidence that speech planning intensifies in the recipient that is selected to respond and that speech planning de-intensifies in the recipient that is not selected. The implications are that next-speaker selection in conversational interaction has a cognitive base: participants orient to it and adjust their planning activity to it—when selected, participants intensify speech planning; when not selected, participants deintensify planning activities.

- Language Development Project (LDP) corpus

Susan Goldin-Meadow, The University of Chicago

The Language Development Project (LDP) corpus represents a significant resource for researchers exploring language acquisition, cognitive development, and multimodal communication. The corpus follows a cohort of 64 typically developing children and 40 children with pre- or perinatal brain injuries, from 14 months to college entry. Originally recruited to reflect the demographics of English-speaking Chicago at the time of data collection (2001), the LDP is also unique in its socioeconomic and racial/ethnic representation.

Video data have been transcribed for speech and gesture, with high reliability at the utterance level, yielding over 1.5 million lines of transcript. All language has been coded for multiple layers of morphological and grammatical characteristics, for both caregiver and child. Language used to express higher order thinking has been coded at the utterance level, in addition to a wide variety of other characteristics (e.g., spatial language, talk about math or the natural world, reading practices).

The corpus includes annual assessment data, consisting of standardized achievement tests, psychometric measures, and study-designed assessments of the children's cognitive, language, and STEM skills, alongside parent interviews, parent IQ, and parent-child problem-solving discourse throughout their elementary and secondary school years (see table below). These data provide a rich portrait of the children and offer insight into the variability of home language experiences.

To date, the corpus has been used to chart the language learning trajectories of children chosen to reflect a widely varying demographic, and the impact that variation in environmental and biological factors has on those trajectories.

One distinctive aspect of the LDP is its commitment to accessibility and collaboration. The project actively seeks data usage agreements with institutions worldwide, fostering a global network of researchers. This collaborative spirit extends across the United States, Europe, and beyond, creating a vibrant and far-reaching community of scholars united by their interest in linguistic and cognitive development.

- M3D-TED Corpus & Audiovisual Corpus of Catalan Children’s Narrative Discourse Development

Patrick L. Rohrer (Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition, and Behavior, Radboud University (Nijmegen, The Netherlands)), Ingrid Vilà-Giménez (Dept. of Subject-Specific Education, Universitat de Girona (Girona, Catalonia)), & Pilar Prieto (Dept. of Translation and Language Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona, Catalonia), Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (Barcelona, Catalonia))

Studying gesture-speech in interaction is a necessary step for gaining a better understanding of multimodal language production. The aims of this presentation are: (a) to briefly introduce the MultiModal MultiDimensional (M3D) gesture coding system, (b) to present two multimodal corpora that have been manually annotated in accordance with M3D principles, namely the "Audiovisual corpus of Catalan children’s narrative discourse development" (Vilà-Giménez et al., 2023, https://osf.io/npz3w/) and the M3D-TED corpus (Rohrer et al., 2023, https://osf.io/ankdx/); and (c) to discuss the annotation of the corpora and their potential future uses.

The motivation behind M3D is to adopt a multidimensional approach by analyzing gestures, considering their form (a qualitative assessment of articulator configuration and kinematics), meaning (gesture referentiality and pragmatic function) and prosodic characteristics (phasing, phrasing and rhythmic properties) independently. Thus, M3D enables the assessment of the relationship between several non-mutually-exclusive dimensions of gesture (semantic, pragmatic and prosodic) with speech. The system has been applied to two corpora. First, the M3D-TED corpus is a multilingual corpus of TED Talks, which contains a total 10 speakers, half of which are in English, and the other half in French. The corpus contains approximately one hour of annotated multimodal speech and includes speech transcriptions, annotations for gesture (M3D), information structure (LISA guidelines; Götze, 2007), and full ToBI annotations for speech prosody for each language.

The “Audiovisual corpus of Catalan children’s narrative discourse development” consists of 332 narratives carried out by 83 children at two time points in development (at 5-6 years old and two years later). All narratives were transcribed and annotated for prosody (Cat_ToBI; Prieto, 2014), gesture (M3D), and Information Structure (LISA).

In applying M3D to the two corpora, we have gained valuable insight into how to improve aspects of gesture annotation, such as assessing the pragmatic functions of manual gesture, or associations with speech prosody. Both corpora are particularly fruitful for exploring further aspects of the relationship between gesture and speech. For the M3D-TED corpus, further work may explore how both gesture and speech may convey various pragmatic meanings or how kinematic aspects of gesture may vary in function of the semantic meaning in speech. For the children’s corpus on narrative discourse, potential avenues of research include further assessment of the relationship between gesture and different levels of linguistic development in discourse.

- The MULTISIMO Multimodal Corpus

Maria Koutsombogera, Carl Vogel, Centre for Computing and Language Studies, School of Computer Science and Statistics, Trinity College Dublin

The MULTISIMO corpus records 23 group triadic dialogues among individuals engaged in a playful task akin to the premise of the television game show, Family Feud. The dataset was collected in 2017 at Trinity College Dublin and the related protocol was approved by the School of Computer Science and Statistics Research Ethics Committee.

The dialogues are carried out in English and their average duration is 10 minutes. Each dialogue has the same overall structure: an introduction, three successive instances of the game, and a closing. Each instance of the game consists of the facilitator presenting a question. Each question was followed by a phase in which the participants have to propose and agree to three answers, and that followed in turn by a phase in which the participants must agree to a ranking of the three answers. The rankings are based on perceptions of what 100 randomly chosen people would propose as answers and therefore the “correct” ranking is in the order of popularity determined by this independent ranking.

Two of the participants in each dialogue were randomly partnered with each other, and the third participant serves as the facilitator for the discussion. Individuals who participate as facilitators are involved in several such discussions (in total three facilitators), while the other participants participate in only one dialogue. The average age of the participants is 30 years old (min = 19, max = 44). Gender is balanced, i.e., with 25 female and 24 male participants, randomly mixed in pairs. The participants come from different countries and span 18 nationalities, one third of them being native English speakers.

Data availability: Following the informed consent of the dialogue participants, 18 of the 23 dialogues are freely available for research purposes (under a non-commercial licence).

Data format: audio & video files (various angles and resolutions), annotation files.

Dataset annotations:

Manual: speech transcription; dialogue segmentation; turn taking (number of turns, duration etc.); speech pauses; gaze; hand gesture; laughter; facilitator’s feedback; perceived dominance; perceived collaboration; self-assessed & perceived personality traits (OCEAN); facilitator assessment.

Automatic: gaze; motion energy; forced alignment.

Research topics: conversational dominance, collaboration in interaction, alignment, personality computing, discourse laughter, gaze detection, among others.

MULTISIMO dataset: https://multisimo.eu/datasets.html

MULTISIMO publications: https://multisimo.eu/publications.html

MULTISIMO citation: Koutsombogera, Maria and Vogel, Carl (2018). Modeling Collaborative Multimodal Behavior in Group Dialogues: The MULTISIMO Corpus. In Proceedings of the 11th Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), Miyazaki, Japan, pp. 2945-2951.

Funding info: MULTISIMO was funded by the European Commission Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowships (IF-EF) grant agreement No 701621.

- MUNDEX: A multimodal corpus for the study of the understanding of explanations

Angela Grimminger (Paderborn University), Olcay Türk (Paderborn University), Petra Wagner (Bielefeld University), Hendrik Buschmeier (Bielefeld University), Yu Wang (Bielefeld University), Stefan Lazarov (Paderborn University)

The MUNDEX (The MUltimodal UNderstanding of EXplanations (MUNDEX)) corpus was built to investigate multimodal interaction dynamics within ongoing explanations (Türk et al., 2023). The aim is to provide a very rich resource (i) for the in-depth understanding of how human interlocutors with their individual strategies are able to monitor and scaffold processes of understanding in an interactive fashion, and (ii) for modelling the monitoring of (non-)understanding in human-machine interaction.

Interlocutors invariably monitor each other’s multimodal behaviour for cues of understanding (multimodal feedback), which are used to adapt the interaction to meet their partner’s communicative needs. It should be possible to use these multimodal cues to monitor the level of understanding of a recipient moment-by-moment in co-constructed interactions. However, the precise interplay of these cues, their functions, their structural distribution and how their use varies between individuals remain largely not well understood.

The explanation scenario in the MUNDEX corpus involves a speaker (the explainer) explaining how to play a board game to a recipient (the explainee). The interactions are filmed in a professional studio using six camera perspectives (1920x1080, 50fps) and multiple dedicated microphones. This enables the separation of audio sources and the capturing of most bodily movements (facial expressions, head, hands, and torso movements), allowing the collection of a rich multimodal repertoire. Further, to associate these multimodal expressions with different levels of understanding, both interaction partners carry out a retrospective thinking aloud task after the interaction session. In this task, the explainees comment on their state of understanding, and the explainers on their belief on the explainees’ level of understanding while watching the videorecording. Timealignment of these auto-assessments with the multimodal data yields information on regions of (non-)understanding, ultimately informing statistical and computational models.

The corpus consists of 88 dialogues between German–speaking dyads (32 explainers, 88 explainees) and their corresponding video recall tasks, totalling roughly 150 hours of data. Semiautomatic transcription of all speech (including utterance, word and syllable level segmentations), and automatic and manual multi-layered annotations of gesture and gaze behaviour (OpenFace, MediaPipe), acoustic information (e.g., pitch, intensity, durations of segments), prosody and discourse are ongoing. For discourse annotations, well-known manuals such as DAMSL and DIT++ (Core and Allen, 1997; Bunt 2009) were adapted. Here, dialogue segments are being tagged with various communicative functions defined based on their potential of affecting the information state of dialogue partners (including (non-)understanding), and with pragmatic relationships between these functions. In addition, these segments will also contain annotations of explanation phases and which game rules they pertain to. Overall, this multidimensional classification provides a foundation for understanding the multi-functionality of dialogue segments, enabling investigations of relationships between fragments of explanations and multimodal behaviour.

References

Bunt, H. (2009). The DIT++ taxonomy for functional dialogue markup. Proceedings of the AAMAS 2009 Workshop `Towards a Standard Markup Language for Embodied Dialogue Acts’, 13–23.

Core, M. G., & Allen, J. F. (1997). Coding dialogs with the DAMSL annotation scheme. Proceedings of the AAAI Fall Symposium on Communicative Action in Humans and Machines.

Türk, O., Wagner, P., Buschmeier, H., Grimminger, A., Wang, Y., & Lazarov, S. (2023). MUNDEX: A multimodal corpus for the study of the understanding of explanations. In P. Paggio & P. Prieto (Eds.), Book of Abstracts of the 1st International Multimodal Communication Symposium (p. 63–64).

- The 3MT_French Dataset

Beatrice Biancardi (CESI LINEACT, Nanterre, France), Mathieu Chollet (School of Computing Science, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, U.K), Chloé Clavel (LTCI, Télécom Paris, IP Paris, Palaiseau, France)

Public speaking constitutes a real challenge for a large part of the population: estimates indicate that 15 to 30% of the population suffers from public speaking anxiety (Tillfors & Furmark, 2007).

Several existing corpora were previously used to model public speaking behavior. In most of them, judgements are given after watching the entire performance, or on thin slices randomly selected from the presentations (e.g., Chollet & Scherer, 2017), without focusing on the temporal location of these slices. This does not allow to investigate how people's judgments develop over time during presentations, under the perspective of sociocognitive theories such as Primacy and recency (Ebbinghaus, 2013) or first impressions (Ambady & Skowronski, 2008).

To provide novel insights on this phenomenon, we present the 3MT_French dataset. It contains a set of presentations of PhD students participating in the French edition of 3-minute Thesis competition. The jury and audience prizes have been integrated with a set of ratings collected online through a novel annotation scheme and protocol. Global evaluation, persuasiveness, perceived self-confidence of the speaker and audience engagement were annotated on different time windows (i.e., the beginning, middle or end of the presentation, or the full video).

We aim at providing two types of contributions. First, the 3MT_dataset with its particular properties:

- A relatively large amount (248) of naturalistic presentations;

- The quality of the presentations is highly heterogeneous;

- The presentations all have similar duration (180s) and structure.

On the other hand, we also provide the following methodological contributions:

- A novel annotation scheme, which aims at providing a quick way to rate the quality of a presentation, considering the dimensions in common between other existing schemes;

- The annotations are collected for both the entire video and different time windows.

This new resource would interest several researchers working on public speaking assessment and training, as well as it will allow for perceptive studies, both under a behavioral and linguistic point of view. It will allow for investigating whether a speaker's behaviors have a different impact on the observers' perception of their performance according to when these behaviors are realized during the speech. The automatic assessment of a speaker's performance could benefit from this information by assigning different weights to segments of behavior according to their relative position in the speech. In addition, a training system could be more efficient by focusing on improving the speaker's behavior during the most important moments of their performance.

The 3MT_French dataset is available here: https://zenodo.org/record/7603511#.Y_cgMXbMJPY

References

Ambady, N., & Skowronski, J. J. (Eds.). (2008). First impressions. Guilford Press.

Chollet, M., & Scherer, S. (2017, May). Assessing public speaking ability from thin slices of behavior. In 2017 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017) (pp. 310-316). IEEE.

Ebbinghaus, H. (2013). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences, 20(4), 155.

Tillfors, M., & Furmark, T. (2007). Social phobia in Swedish university students: prevalence, subgroups and avoidant behavior. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 42(1), 79- 86.

Interactive Sessions

- Automatic Annotation of Multimodal Language Corpora

Led by Abdellah Fourtassi, Aix-Marseille University

The goal of this session is to discuss current advances in the automatic annotation of multimodal data and the challenges regarding their practical use for corpora recorded in more or less naturalistic settings. As an introduction to this discussion, I will provide both a broad overview and specific concrete examples – based primarily on research in my lab – of where and why automatic annotations did or did not succeed, including:

- Speech Recognition and Transcription

- Speaker Diarization

- Dialogue Acts

- Facial expression (e.g., smile)

- Gazing pattern

- Head/hand gestures

After this introduction, participants can share their own experiences using automatic models on their corpora and/or their thoughts on what would be the most needed tools in their specific research area. This discussion could provide the basis for a community of researchers with similar/complementary interests to continue sharing expertise and methods.

- Similarities and Differences in Annotation Systems

Led by Ada Ren-Mitchell, MIT Media Lab

In a recent conference, the MultiModal Symposium in Barcelona, we noticed that there are sometimes surprising differences in how we label gesture phases (i.e., preparation, stroke, recovery phase etc.) in practice. There may be other assumptions that we may not be aware of. This is an issue for the field, as our differing definitions and practices in our methodologies can cloud our understanding of each other's work, and slow our progress as a field.

In this workshop session, we will explore our shared understanding of multimodal research methodologies and goals. Prior to the workshop, participants from different labs were invited to annotate in ELAN the same short segment of video from 2 different speakers for manual gestures and gesture phases. Analyzing these annotations, we will identify variations in different research labs' definitions of multimodal features. During the session, we will compare the annotations and identify significant differences in definitions and practices. The aim of the workshop is to highlight the importance of specifying clear definitions of categories used in annotation systems, and begin to develop recommendations for how to describe the conventions most effectively to be understood across different research labs. The ultimate goal is a clearer understanding of what each of us has actually done in our work, and how to interpret each others' results.

- Multimodal Dialogue Corpora: Ethical Considerations & Data Sharing

Led by Carl Vogel, Trinity College Dublin

This session begins by outlining positions on ethical issues and legal issues associated with the collection and analysis of multi-modal dialogue data, including analysis by the wider scientific community outside the group who constructed any such corpus. The positions are influenced by reflections on our own experience in corpus construction and collection of related data sets. The interactive session is intended to establish the extent to which the positions are shared across the community as well as the parameters of variation.

- Real-world Applications for Corpora

Led by Beatrice Biancardi, CESI LINEACT

You finally collected (or downloaded) your corpus, congrats! And now?

Applications of multimodal corpora span different domains and goals. For example, corpora can be used by researchers in AI or human-centered computing as input for computational models to predict or generate human behaviour. On the other hand, corpora can also be analysed by researchers in Linguistics or Cognitive Science to better understand the phenomena underlying human behaviour. Different applications = different corpora?

Despite a huge number of available multimodal corpora exist, very often researchers prefer to spend time and resources to create their own corpus. Why? What is missing? What should be the characteristics of a corpus to be useful for different tasks?

After giving some examples from my previous and current work, this interactive session aims at identifying the most common applications of multimodal corpora and the needs of researchers coming from different domains. We will explore the common issues of existing corpora in order to outline some general guidelines to make a corpus more attractive and exploitable by researchers from different domain.

Close

Close