IAS Turbulence: Of Parables, Patterns, and Progeny — Rethinking Trans Theory with Octavia E. Butler

Ama Josephine Budge & Christine ‘Xine’ Yao in conversation

16 April 2020

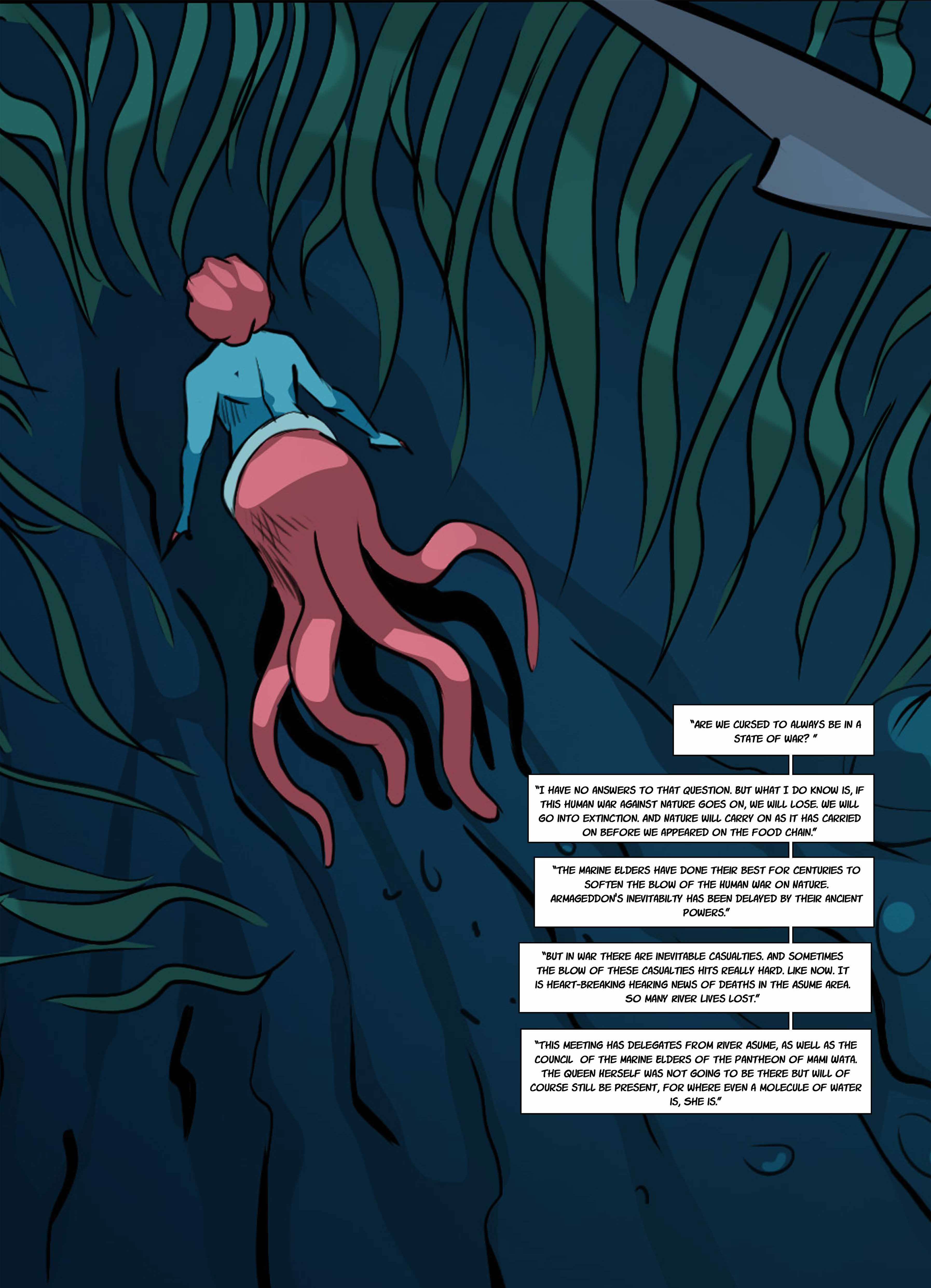

Akosua Hanson, ‘Underwater Dreams’, Moongirls, vol. 3, p. 10 © Drama Queens Ghana. Courtesy of the artists.

The following conversation took place via email over a series of weeks between Ama Josephine Budge, and Dr Christine ‘Xine’ Yao. After meeting on a panel at the IAS on 6 February 2019, Ama and Xine have become friends, correspondents, collaborators, and allies. This conversation on the work of the incredible Octavia Butler is a minuscule window through which to view a fraction of the wonderful, weird, empowering, and inflammatory challenges/corroborations that have since taken place. Octavia Butler (1947-2006) was an acclaimed writer of speculative fiction, the first to win the MacArthur Genius Grant. Her work has been a major influence on many literary traditions, including the creative and critical practices of Black speculative imagining which is sometimes called Afrofuturism. Butler’s canon remains for Black folx worldwide, as Professor Zenzele Isoke commented at the 2019 National Women’s Studies Association Conference, akin to a biblical text. Her rigorously detailed, complex, nuanced, and vast explorations of race, gender, capitalism, biopolitics, affect, class, borders, and American history through both her published and unpublished fiction and non-fiction works make up a painfully unacknowledged core of Black history which nevertheless continues to inform and inspire writers, artists, researchers, politicians, scientists, and, of course, readers worldwide.

Xine Yao: So let’s be frank: the most turbulent issue in UK feminism right now is trans inclusion. How can we read Octavia Butler’s work with trans in mind? Moreover, Butler allows us to address another structural issue that cannot be separated from trans inclusion: race and the legacies of colonial science.

In her iconic essay ‘The Race for Theory’ (1987), Black feminist literary scholar Barbara Christian writes,

For people of colour have always theorized – but in forms quite different from the Western form of abstract logic. And I am inclined to say that our theorizing (and I intentionally use the verb rather than the noun) is often in narrative forms, in the stories we create, in riddles and proverbs, in the play with language, since dynamic rather than fixed ideas seem more to our liking.

Following Christian’s insight into the relationship between storytelling and theorizing for Black feminism, Octavia Butler’s science fiction is itself beautiful, complicated speculative thinking. She writes about the past, the future, and presents almost parallel to our own: foregrounding trans possibilities in our reading, how does she enable us to disrupt an essentialist deracinated universal Woman as well as trouble investments both in archival genealogy and projections of the distant future that depend upon the presumption of a (white) reproductive futurity and its nostalgic corollary?

Ama Josephine Budge: So, naturally, I would reply that the most turbulent issue in UK feminism right now is in fact the way that gender binaries, transphobic ‘feminisms’ (I use inverted commas because I do not consider them to be feminist) and trans rights have become the central issue in contemporary feminism rather than the patriarchy and its control of minoritized bodies – which is to say, essentially, power. One of the most exciting aspects of Butler’s work is her ability to continuously re-centre structural issues of power, domination and, at times, so slippery, seductive oppression over segregated ‘single-issue’ arguments. For me, that ability continues to be so much more radical than many of the ‘trans’ (gender/human/racial) conversations in the West which are so often still dominated by colonial, racialized, classed, and patriarchal modes of relation.

I love the Barbara Christian quote you invoke to open this dialogue and I’d like to bring some critical attention to the gender theories that Butler experiments with and asserts throughout her fiction. Of particular interest to me, and perhaps a good example of the sticky and subtle politic I’m trying to insinuate in the paragraph above as well as in response to your excellent question, would spring from The Patternist Series. It begins with Anyanwu (later known as Emma) who, amongst many other things, is able to change her shape. At the start of the first book in the series Wild Seed, she meets Doro, another ‘human’ with extraordinary abilities: Doro cannot die. Yet rather than being able to shape and re-shape his own form, Doro must take the bodies of others. He has been, during the hundreds of years of his life, white, Black, male, female, child, elder, dying, healthy, powerful, poor.[i] He has learnt to wear identities like a cloak, like a tool to achieve a purpose. As the only being he’s ever met who can change and heal her own body enough to outmanoeuvre death, Doro becomes obsessed with Anyanwu, trying to control her and her ‘seed’. One thing he insists on, that Anyanwu finds completely repugnant and unthinkable, is that she should take the form of a man in order to make love to him in the body of a woman. Eventually she is forced to do this and Butler writes how he tries to pleasure her with his mouth in ‘female’ form.

So whilst their relationship goes on to become more nuanced and mutually invested, at this point we have the very image of the undying, parasitic, abusive, controlling, patriarchal ‘male’ in our minds eye forcing the one he wishes to oppress to take the body of a man so that he, as a woman, might pleasure and be pleasured by ‘him’. Suddenly we aren’t talking about gender any more, we’re talking about power. It remains one of the most affecting analogies of the ways in which patriarchy does not trans-cend but is woven throughout the complexities of gender, race, and origin. She highlights both its centrality to their existence, as well as the way patriarchy is so persistently forced from view as we ‘call in’ and ‘call out’,[ii] ostracize and reinforce ‘black and white’ delineations of ally and enemy, self and Other. Ever pushing one another’s heads under the water so that we in turn are further from drowning. We are so uncomfortable in the turbulence.

XY: Love this reading of Doro and Anyanwu! The turbulence of bodies but the persistence and malleability of power. Butler shows how biological ‘sex’ is not an essential determinant of these hierarchical relations. Both main characters have fluid selves – so one might say gender-fluid but all aspects are fluid – yet it is striking how she writes the manifestations of their power in such different ways: transmutation versus possession. In that scene between Anyanwu and Doro there are tensions between the characters’ pronouns and how we might read their bodies in that moment in cisheteronormative phenotypical ways. Their identifications do not have to map onto stable configurations of gender expression and sexual orientation. I think this is so important given expectations about the legibility and therefore the viability of one’s identification as trans or queer or non-binary.

To your use of ‘parasitic’ I am reminded of her classic Bloodchild, which she has called her ‘pregnant man story’. Pregnant trans men are perennial subjects of media fascination in ways that hold each case up as an exceptional curiosity. For instance, in September 2019 there was a legal case in the UK where a trans man was unable to be registered as the father of the child he had borne. Do you have thoughts more broadly about representations of reproduction in Butler’s work?

AJB: I mean there’s so much in here isn’t there? Even the use of the term ‘seed’, which at least in gendered conversations, is usually reserved for semen and dates back to social beliefs that cis men created all the traits perceived as ‘good’ in babies (usually gender binary so strong/meek, clever/compliant, handsome/beautiful, confident/timid, etc), whilst the feminized body that bore them were responsible for any and all ills, deviations or mishaps – i.e. ‘he’s strong like his father’ or ‘he’s weak and sickly, like his mother’. These beliefs were of course reinforced by medical professionals and publications who valorized or initiated the punishment and institutionalization of women through acts such as declaring women infertile, unsuitable/unsafe mothers, hysterical, etc. Yet for Butler, seed is power or magic. She initiates the conversation with particular prevalence with ‘Earthseed communities’ in the Parable duology, continued really beautifully by Junauda Petrus in The Stars and the Blackness Between Them (2019), about returning Black and oppressed people to the land, to growth, to agriculture, through a dynamic other than slavery. Returning to the Patternist series, Butler also creates an interesting reproductive dynamic because those that are later called the Patternists (who are essentially telepathic, amongst other things) cannot raise their own children. They are paired, first by Doro, then by themselves based on compatibility of power – what combinations of ability would make the strongest, most magically talented children. Yet their hyper-sensitivity to one another makes them unable to parent safely; they often brutalize, abuse, or simply abandon their babies and children.

So I suppose my question might be rather… if gendered behaviour is a construct – learned, performed, mimicked, forced, re-inforced, conditioned, and punished if deviated from – are we (or was Butler) working towards a gender-fluid – as you put it – future, in which the bearing of children becomes generalized, possible for some bodies without medical assistance (just as it is currently for some cis women), not possible for others? Then, subsequently, those best suited to parenting do the child rearing and those that have children don’t necessarily raise them? Butler lived and died in and out of poverty, she would have seen young families, young children torn apart by illness, oppression, racism, abuse, violence, addiction, the judicial system and more, perhaps for Butler it was more about responsibility, about joy, about safety than the specifics of identification and genetic family. In many ways, the early Patternists return to an ‘it takes a village’ child-rearing model.

And I worry too that as queer community, our consistent (and often necessary) reaction to the policies that are consistently made and re-made to confine us, to hem in all that we can be, is just a way to keep us playing their game, just a distraction from being or becoming free. For example, take the continued and important fight by queer womxn and lesbian couples to access scientific methods of reproduction that either include two sources of ovum (one from each party) as well as sperm, or manipulate the eggs’ chromosomatic make-up so that no sperm is required for germination. I myself am a part of this conversation – how much my partner and I want to be able to conceive a child without a (possibly unknown) third party – and yet, does this not continue to force us into nuclearized, isolated family models that prioritize genetic (and therefore at least historically patriarchal) ties and understandings of legacy? Such models can undermine notions of queer family-making, of de-gendering genetics, of de-prioritising ‘blood relations’ in favour of adoption and fostering models, etc. I see Butler playing with all these dynamics and contradictions in ways that can offer extremely generative challenges and critiques to modern understandings of gender, reproduction and family-making. She reminds us through the Patternists that we must always pay attention to who is benefitting from particular genetic unions, relationships and even family-unit households.

XY: In Bloodchild, the ostensibly cismale human protagonist offers his body as the incubator for the ostensibly cisfemale alien’s eggs that she injects into him by penetrating him with her ovipositor. This is her ‘pregnant man’ story: she blurs distinctions between parasitic and symbiotic dependencies. Any human can incubate these alien eggs. Our attention is directed to ungendered human reproductive labour. Nonetheless, what we would consider heteronormative human reproduction still persists: the alien race Tlic have a vested interest in the continuation of the human species because their own reproductive cycle is dependent upon warm mammalian bodies that can incubate their young – and it is better if the hosts are willing, an arrangement in which the ideal of free consent is dubious. Butler forces us not to get comfortable with an easy understanding of ‘queer’ that could be co-opted into a homonormative agenda.

There’s a difference between abolishing gender roles and abolishing gender itself. Butler claimed that the story was not about slavery but about ‘how the rent gets paid’ if we as humans did find other life forms. Still, to use Saidiya Hartman’s phrase, the ‘afterlife of slavery’ endures in Butler’s imagining of a human future. The persistence of gender as a means of identification is not reducible to a simplistic approach to bodies or labour. New configurations of these relations cannot fully divest from the old. In this regard, taking Butler’s narratives as theory I think we can discern that she would agree that trans does not reify the gender binary nor does it seek a naive abolition. There has always been turbulence: it is neither good nor bad. It’s just that some of us have always realized it more than others.

[i] In capitalizing ‘Black’ but not ‘white’ we follow a political practice that references an interdisciplinary history of the Black Radical Tradition both within and outside of academia. In brief, this practice follows Du Bois, Angela Davis and many others who argue that Black folx are still not seen as human equals; therefore, to capitalize Black here is an acknowledgement that whilst the others are of course categories with which power/privilege/dominance is afforded, Black remains a politicalized category built solely on the construction of a violently dehumanized labour force, the afterlife of which continues today.

[ii] ‘Call in’ and ‘call out’ are vernacular ways of naming practices of calling people to accountability: the first is intimate, the other public.

Close

Close