UCL History student Fleur Haber on interviewing her grandmother about Jewish history and WW2

30 April 2020

In this short article, UCL History student Fleur Haber discusses her personal oral history project, which has seen her interview her grandmother about her experiences and memories as a Jewish child in eastern Europe during WW2.

The ways in which the lives of my grandmother and her family were shaped by the Tsarist, Nazi and Soviet regimes is interesting and dramatic, and she has always enjoyed talking about her past. My appreciation for her experiences, and for the opportunity to hear about them first-hand, has grown since I was a child. Studying history has made me value her experiences even more. I have learned the importance of preserving evidence wherever possible; for the last generation who will have the opportunity to hear them speak for themselves, there is a need to record the memories of Holocaust survivors.

My grandmother – Halina Moss, nee Lewiner, born in 1929 – has told me many of the memorable things that happened to her family, such as the day a bomb fell at the end of their garden to announce that the invasion of Poland had reached them. Her mother persuaded her father to join the stream of refugees on the road from Warsaw, thinking that the risk to women and children was smaller. They followed later, leaving everything behind. Although this journey was undertaken by countless Polish people, Jewish or not, other aspects of her family’s experience were less typical.

Chaim Shimshon/Semion and his wife Miriam Sarah/Marya Sonya c.1958 in Glasgow with their oldest grandchild

Halina’s father, Chaim Shimshon (Semion) Lewiner, was a Bundist, exiled once by the Tzarist regime for his revolutionary activities, and then again under the Communists. He was born in 1887, and as a teenager began to work for a firm which embroidered insignia for military uniforms, ideally placing him to act as a liaison carrying messages between revolutionaries. She explained to me his reasons for becoming involved with political activism. He wished to fight for rights for Poland’s Jewish community, who experienced persecution and discrimination even before the war began. For example, Chaim Shimshon and the others with whom he worked aimed to help Jewish people find employment in a society where many employers were reluctant to hire them; when Warsaw’s public bus system was persuaded to employ three Jewish people, they considered it a great achievement.

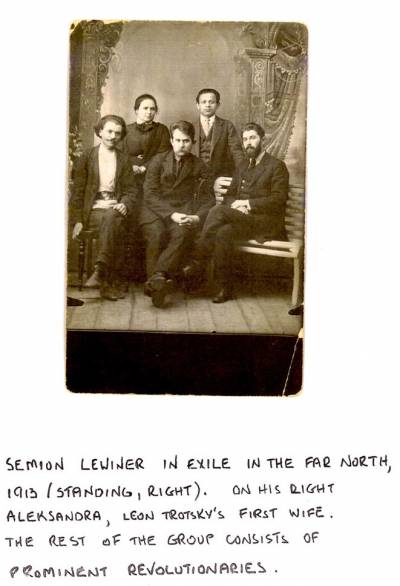

Eventually Chaim and a group of others were warned that they were being watched by the police. They were caught while trying to escape across the German border and Chaim was sent east, with a sentence of detention rather than hard labour, as there was insufficient evidence to charge him with any specific crime. While there, he was given an allowance and spent time among intellectuals who had also been exiled. We discovered a photo from this time in a biography of Trotsky in which Chaim Shimshon is sitting with a group of revolutionaries including Trotsky’s first wife. This experience enabled him to gain an education in a way he had not been able to when he was younger.

The clearest parts of the story are the times my grandmother herself can remember. During the Second World War, she, her parents, and many members of her mother’s large family came to be in Bialystok, in Russian-occupied Poland. There they were offered a choice between becoming Soviet citizens or going back to Poland, and although most of the family became citizens and stayed in Bialystok, her parents preferred to return to Warsaw. They were put on trains but actually taken to a labour camp in Archangel in the North of Russia.

It was in Archangel that Chaim Shimshon was again arrested and sent away, this time to a gulag, after testifying in someone else’s trial and being denounced by the convicted man as a Bundist. His sentence illustrates the instability of the times and the unpredictable, often unjust nature of life under the Soviet regime. It also conveys an important message about perspective for a historian. The deportation to the east and his imprisonment must have been terrible to cope with at the time and seemed like the most awful thing that could happen. Yet of all the family members who had been in Bialystok, only my grandmother and her parents survived the Holocaust, having been transported beyond the reach of the Nazis.

The experience of recording an oral history with my grandmother was very different from the research I usually do for coursework and exams. Scholarly books generally identify facts that are important within the historical narrative, the kinds of things that affect the overall situation, and are remembered widely for their significance. Of course my grandmother is aware of these events. She remembers hearing adults discussing the escalating crisis, the sounds of warplanes, and the stream of refugees arriving in and leaving from Warsaw. She knows about the concentration camps and the gulag, and the official dates of the war’s beginning and end. Even some of the more personal features of her story, such as her Uncle Avram’s disappearance from Moscow, arrest and supposed sentence to 10 years hard labour (really he was shot in the basement of the Lubyanka prison) are part of well-known historical events – in this case the Great Terror.

However, interviewing my grandmother was different because of the unique perspective she provided. She remembered through the eyes of a child, recalling details which were important to her at the time. A particularly moving story took place after the war, when she and her parents were returning to Poland, travelling by train through Russia. They stopped at Berdychiv, where a renowned centre of Jewish learning had been wiped out, and her resolutely secular father bought sacred texts from a trader who was using the pages to wrap vegetables, because he could not stand to see them used in this way. These details transform an academic story into a human one, even, I hope, for an audience that is not as closely related to the subject as I am.

Close

Close