Black History Month: An Interview with Dr Ali Bennett, recently completed PhD candidate

31 October 2019

We spoke to Dr Ali Bennett about her research on the material and visual histories of eastern Africa during the British colonial era and asked her to tell us about some of the important figures that she has come across.

Hi Ali! Can you tell us a little about yourself, and your research?

Hello! I am a historian of the British empire, particularly in eastern Africa. I study imperialism in the region from a material and visual perspective. I completed my PhD earlier this year through UCL History and the British Museum with the support of an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award. The thesis used museum collections as a basis for exploring the activities and interactions of local elites, colonial officials, missionaries, and colonial institutions (including museums) through the lens of the material world. During the course of my studies I was lucky enough to conduct research in archives and museums across the UK, Kenya, Uganda, and Zanzibar.

Why did you choose to research your PhD topic?

The project was part of the Collaborative Doctoral Partnership scheme and so was initially highlighted by staff at the British Museum and UCL as a topic that required much deeper research. The idea was to piece together the provenance of eastern African collections in the British Museum as well as other repositories in Britain and across eastern Africa in order to shed new light on the cultural dynamics of imperialism and collecting in the region. This research ties in with both the material turn in the New Imperial History, and the growing momentum to better understand the provenance and formation of colonial-era museum collections. One of my key aims was to shed new light on Afican actions and experiences in these histories.

Can you tell us about an interesting case study?

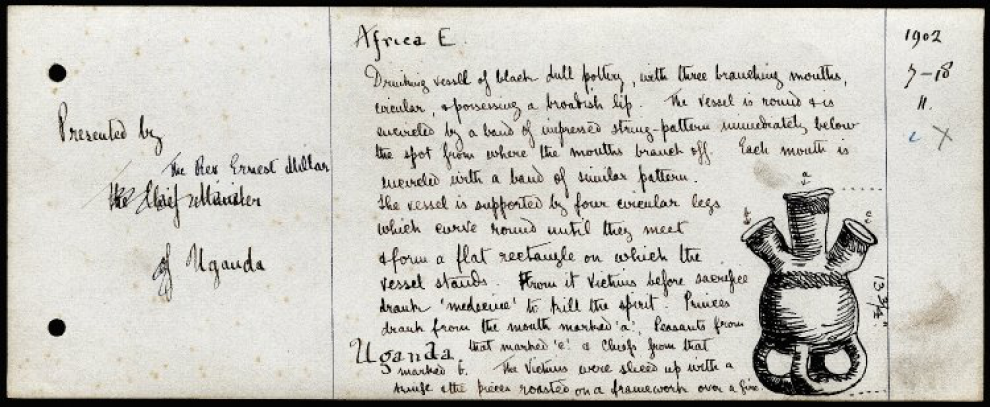

Early on, I stumbled upon a British Museum accession slip for an item of Ugandan pottery. The slip attributed the object to a Protestant missionary. Yet on closer inspection, I noticed a second name crossed out. The original name reads ‘The Chief Minister of Uganda’.

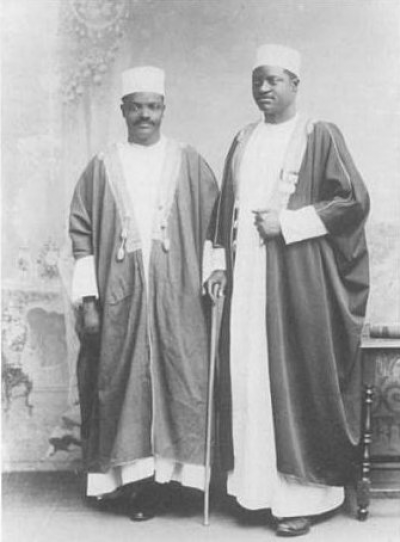

Upon further research I found that this must have been Sir Apolo Kaggwa (1869-1927), the Prime Minister or ‘Katikkiro’ of the Kingdom of Buganda. Kaggwa had travelled to Britain in 1902 with his Secretary, Hamu Mukasa (1870-1956) on an official visit for the coronation of King Edward VII. The missionary had accompanied them as their official chaperone. The discovery of Kaggwa’s crossed-out name led to me finding numerous other donations by Kaggwa including thirty-one objects to the British Museum, sixteen to Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, and other objects to King Edward the VII and the Royal Collection. I have also found objects at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. that are linked to Kaggwa who appeared to be engaging in a strategic global project of gifting certain Ugandan objects to museums. This is an activity traditionally attributed to white, European males.

Ham Mukasa and Apolo Kaggwa in London, Cambridge University Library, Royal Commonwealth Society Library, RCMS 113/38/3/ 31

Among historians of Uganda, Kaggwa is generally considered a self-styled gatekeeper of Uganda’s written history. He began writing in 1890, having been taught to read by missionaries at the Buganda court. In 1901, he produced the first published record of a unilineal Kiganda history in the Luganda vernacular entitled The Kings of Buganda. In tracing a long history of Ugandan leaders, and including himself in these records, Kaggwa secured his own name within the newly-written annals of Ugandan history. Tales of Sir Apolo: Uganda Folklore and Proverbs was likewise a powerful, but largely biographical book in which he presented himself as a commoner who had ascended the court of Buganda as an able gatekeeper and mediator of its cultural practices.

Kaggwa was a complex figure. Many academics, and indeed commentators at the time, critiqued his alliance with British missionaries and colonial officials. His collecting and gifting of Ugandan material culture to British museums can’t, therefore, be treated as representative of some wider ‘Ugandan’ experience during the colonial period. In other cases, Ugandans faced violent removal of their material belongings by British forces. It was Kaggwa’s elite status that enabled him to travel to Britain to give his gifts. Thanks to the increased land ownership rights he gained under the 1900 Buganda Agreement, he was essentially one of the top ‘landed aristocratic’ elites in Uganda. But his history writing, object collecting, and gift giving were a reaction to a particularly turbulent, violent, and transformative moment in Ugandan history as he, like others, sought to navigate the shifting hierarchies of the emerging colonial landscape and present a strong political and cultural self-image.

Black History is obviously central to your research – why do you think Black History Month is so important?

Black history should be part of our narrative all year round. But the event offers an important opportunity to illuminate and commemorate otherwise invisible or forgotten figures that have shaped the history of Britain and the wider world; in this case through the formation of global museum collections and knowledge systems.

While Kaggwa’s written legacy is still strong and visible, most of his object collections have lain practically dormant in their museum settings over the past century. This is partly because he is not easily visible in the museum records themselves. In the digital record for his pottery item, his crossed-out name was entirely removed and replaced with the missionary who accompanied him. This is just one example of the partial and selective nature of museum records, but it raises important questions about who else might be missing. It also shows the much richer picture that can and must be achieved for our museum collections and shared histories if we look hard enough.

What are your plans for the future – any new research on the horizon?

My new research project takes a more global approach to eastern African material culture in the colonial era. This new line of research will examine the various global trajectories of the region’s ivory to both Britain and North America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But crucially, it will pay more attention to the socio-cultural dynamics of the trade from the perspective of the East African source base than has previously been offered. In doing so, I hope that it will shed new light on the local, national and global forces that facilitated this destructive industry.

Close

Close