Dr Eva Miller awarded 3-year British Academy postdoctoral fellowship

30 July 2019

UCL History is delighted to announce that Dr Eva Miller has been awarded 3-year British Academy postdoctoral fellowship. We spoke to Eva about her new project.

Congratulations on your British Academy postdoctoral fellowship! Can you tell us a little about the project that this is supporting?

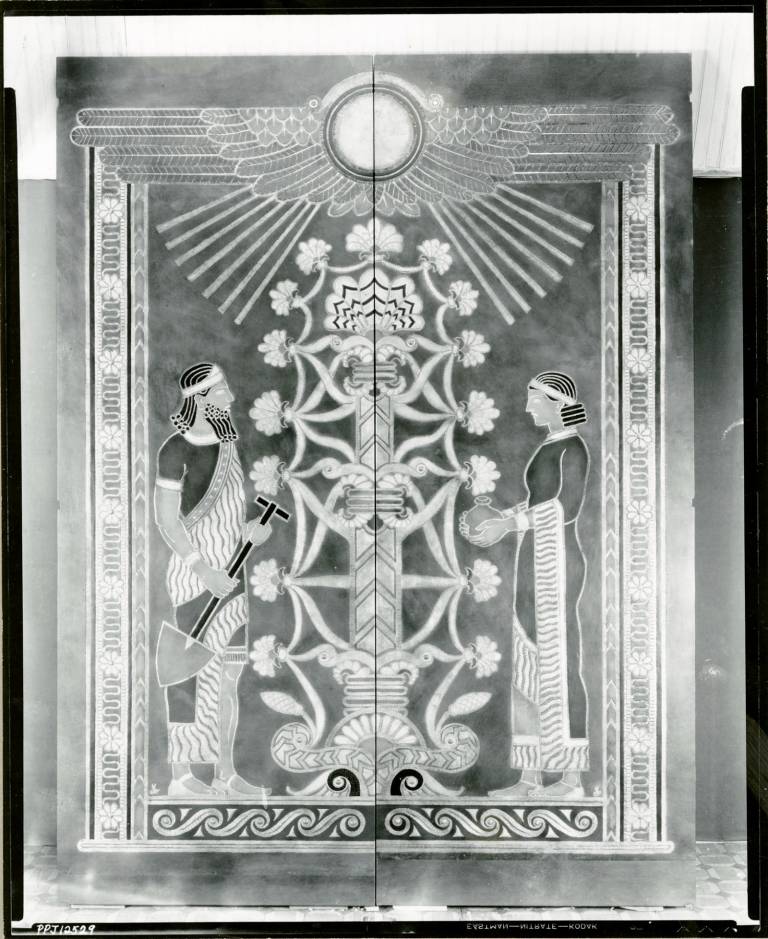

My project is called 'A New Antiquity: Western Reception and Revival of Assyrian Images in Decorative Arts, 1850-1935'. As the title indicates, it's a project that is about things that are very ancient and things that are--self-consciously--very modern all at once. The 'new antiquity' I'm looking at emerged in the mid 19th century when European diplomats and explorers started to excavate mounds in what is now northern Iraq and discovered the awe-inspiring ancient palaces of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (9th-7th cent. BCE). Assyria was well-known as an arch-villain in Biblical narratives, and from a few exoticising Classical references, this was the first time anyone in thousands of years was coming face-to-face with its art. I'm interested in how the imagery that came out of these excavations entered a wider Western consciousness, where it was taken up by artists, architects, civic leaders, business people, and politicians for different, often surprising, ends. My project focuses on the kinds of images that people lived and worked around: architectural sculpture (the single biggest strand), book design, commercial illustration, film and theatre design, things that truly became a part of the fabric of the modern Western world. I've realised already that studies of modern arts and culture have overlooked how important ancient Assyria once was, perhaps paradoxically, for constructing a self-image of what it meant to be a modern Westerner.

My project stops at 1935, but we see that 'revival arts' are still relevant in unexpected ways; you might have seen recent news articles about Boris Johnson wearing socks depicting the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal while on the leadership campaign trail. Many papers speculated that our now-PM identified with the ancient king (no one tell him Ashurbanipal's reign is increasingly regarded as the beginning of the end for Assyrian unity and political power). Perhaps he was also have been thinking of long traditions that associate Assyrian imagery with British imperial power ('spoils of Empire'), or thought the socks said 'loveable, well-educated eccentric'. This is just one example of the weird and unexpected new meanings Assyrian images have taken on since their rediscovery.

Why did you choose to complete this research at UCL?

UCL is completely unique in the UK in having a history department in which the ancient Middle East is studied and researched alongside the modern world. This is more than an administrative arrangement: this arrangement signals that UCL recognises the important links between ancient and modern histories, in terms of practice and in terms of their value to how we understand the world around us. It’s also great for me at a personal level; for this project I'm essentially moving from being an ancient Near Eastern specialist to being really more of a modern historian--a big leap. Luckily, I'll have colleagues who can talk to me about both 'ends' of this work (and help me figure out how to work with paper archives instead of cuneiform clay tablets!). And of course, being at UCL also means there are incredible opportunities for collaboration and interdisciplinary events, both within the university and outside of it.

What do you hope that this project will achieve – what will be its impact?

The major outcome of the project is a website on my central topic, through which I hope that enthusiasts from many backgrounds will discover new ideas. That includes students and academics, but also fans of modernist art and architecture, members of the Assyrian and Iraqi diaspora in the West, history buffs, contemporary artists, and conservationists. I also hope that this project can serve to document art and architecture that is at risk of being lost or forgotten. Understanding the unique nature of this 'Assyrian Revival' style could, I hope, assist in preservation bids and help guide decisions about how to manage buildings and artworks that we still live and work with today.

In a sense, this project is a study of 'impact' in itself. A major question that I want to answer is how--in a very literal sense--images and associated knowledge got from archaeological sites and museums to the imaginations of illustrators, sculptors, architects, civic leaders, business people, and filmmakers. Ultimately, this is a project about how people came to know what they knew and how they gave meaning to certain images and idea. This kind of 'history of knowledge' can inform how we practice as historians, and help make all of us, professional historians or not, better consumers of historical information.

Close

Close