2 October – 28 February 2018

Exhibition

Octagon Gallery, Wilkins Building, UCL

The severed heads of two famous scholars have spent the last few decades hidden from public view. Both were men strongly associated with UCL that consented to have their remains preserved for future generations to display, research and discuss. Here we exhibit the head of philosopher Jeremy Bentham for the first time in decades, alongside cutting-edge scientific techniques to extract and sequence his DNA. We also consider why the archaeologist Flinders Petrie left his head to science, and explore how the actions and work of both men have influenced our modern attitudes to death and what it means to be human.

By looking at Flinders Petrie’s and Jeremy Bentham’s heads in the context of their own scholarship, alongside current scientific advances and other human remains from UCL's collections, 'What does it mean to be human?' Examines the power of human remains to generate debate and critical reflection. Come and explore these issues in archaeology, history and philosophy of science, evolutionary science and ancient DNA research in this exhibition and accompanying events series.

Funeral stationery for Louisa Galton

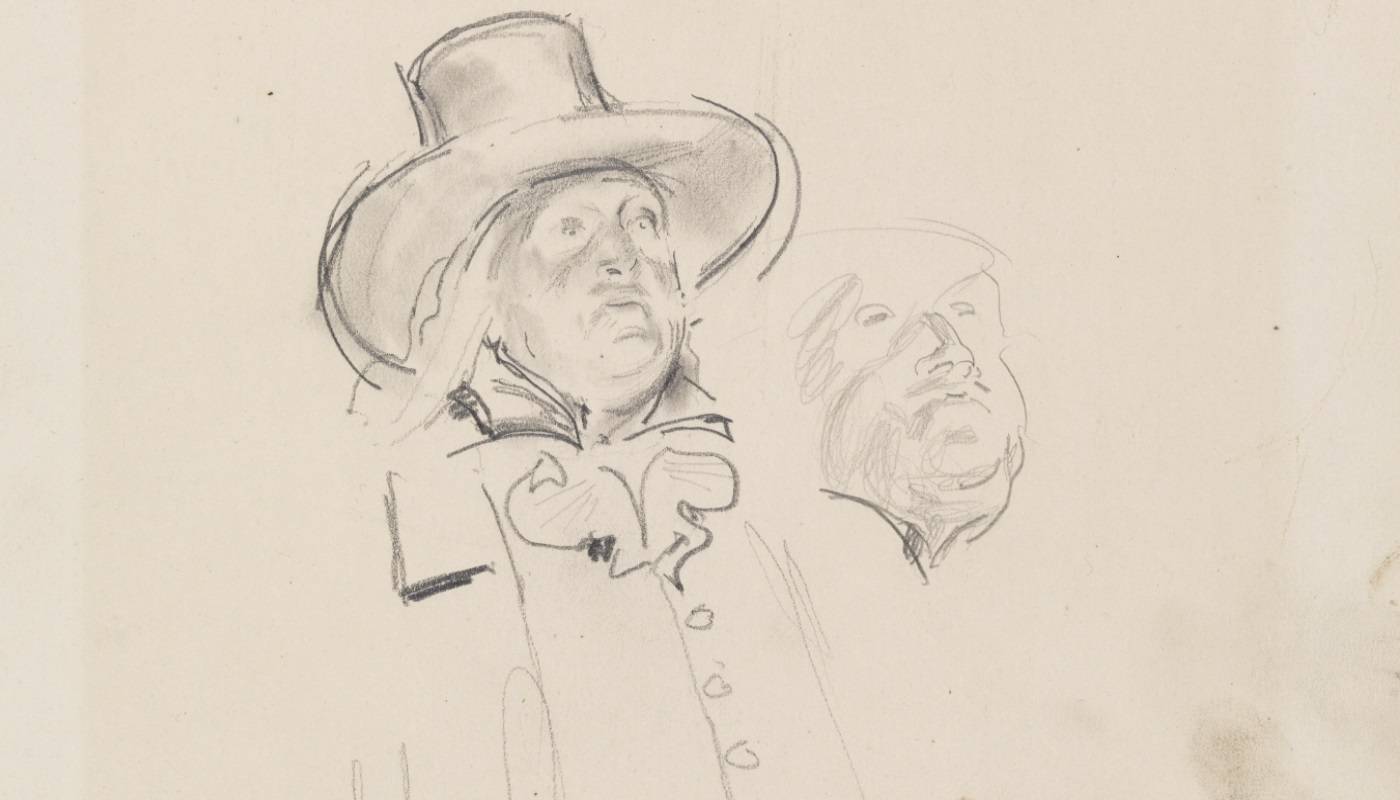

'Study for the Four Founders' by Henry Tonks

Preserved head of Jeremy Bentham

Bentham's genome

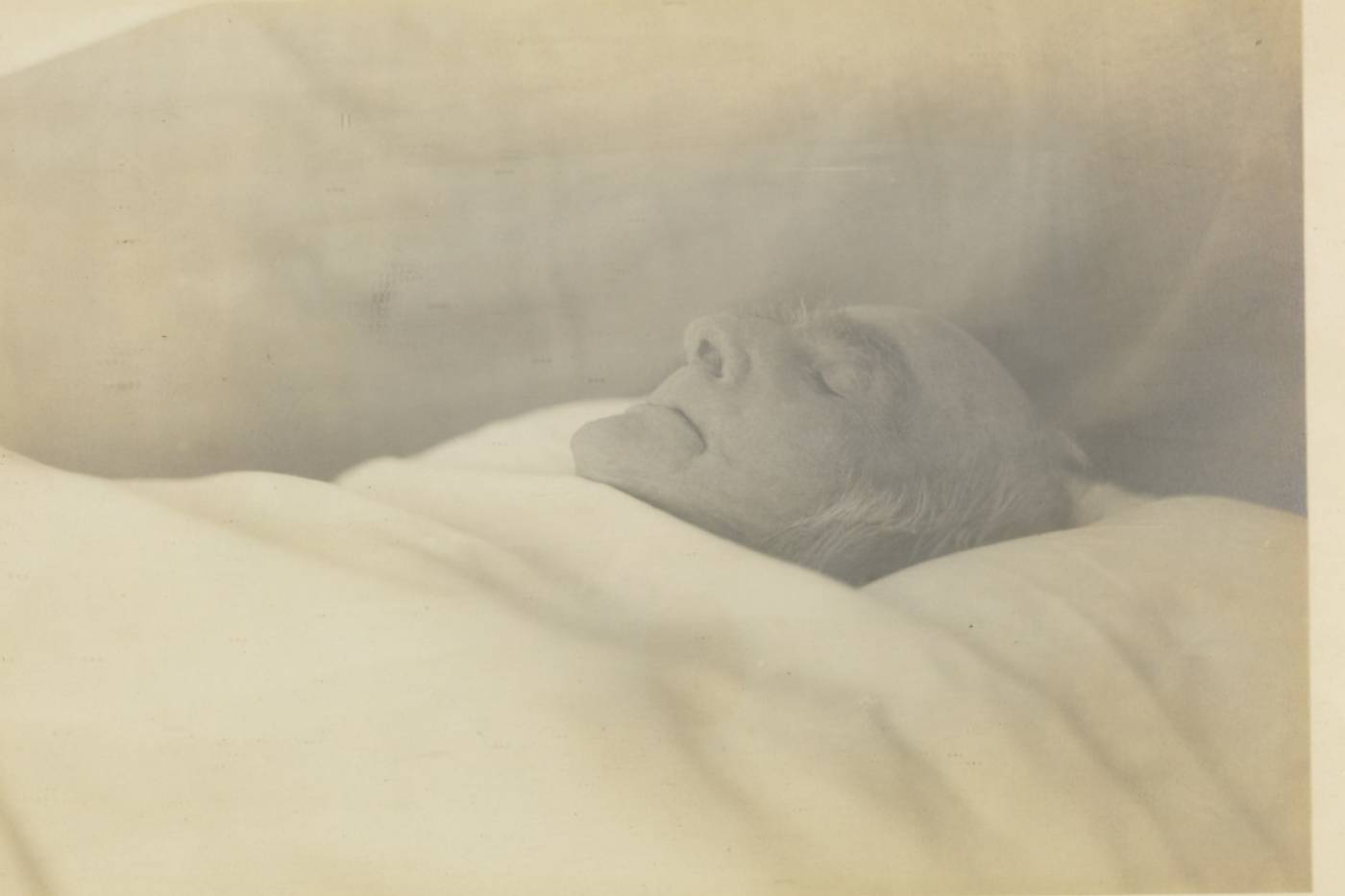

Francis Galton on his deathbed

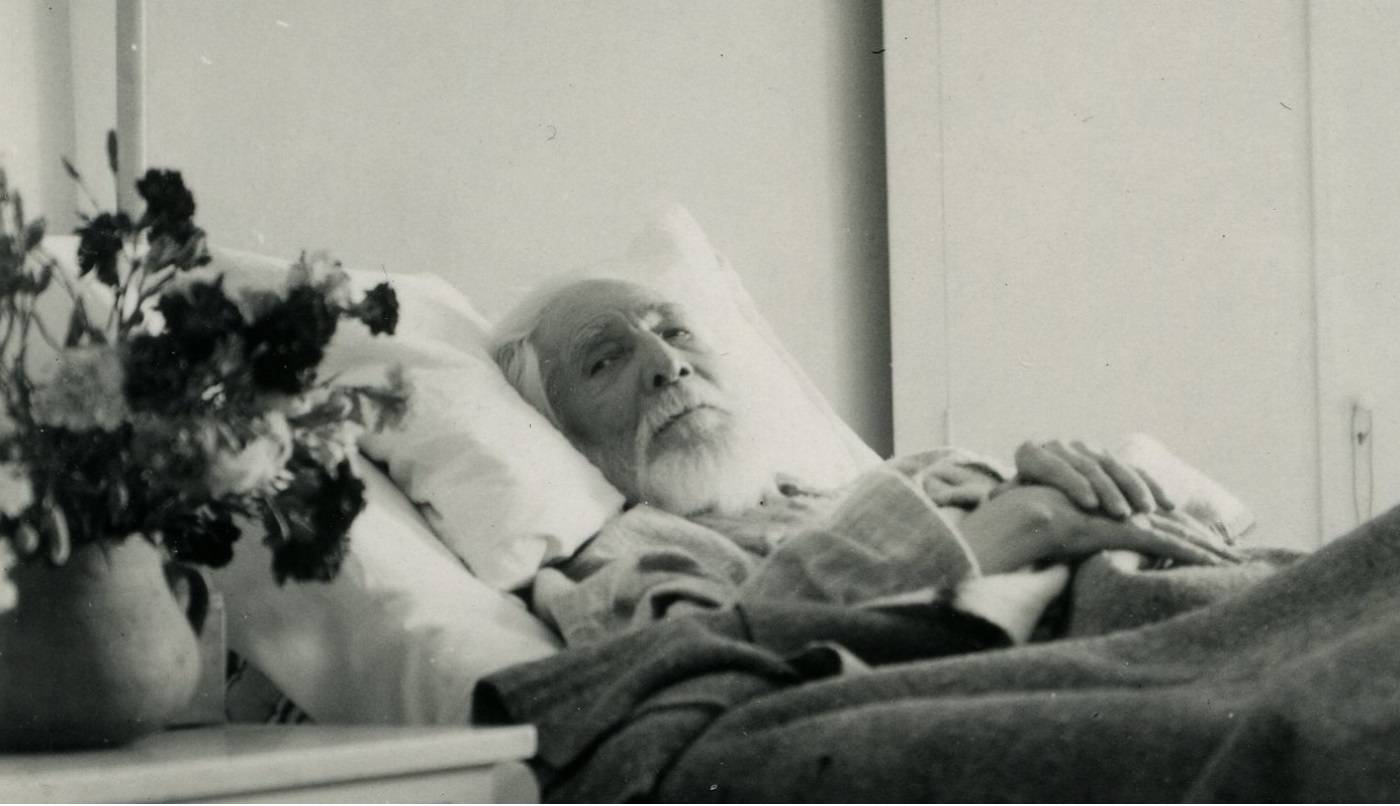

Flinders Petrie on his deathbed

Events

What does it mean to be human? Through talks, workshops and a late opening discover how we use science to understand the dilemma of death.

The Head of Flinders Petrie?

Wednesday 6 September, 1.15-1.45pm

Talk

Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

Find out more about the so-called head of Flinders Petrie that is stored in a jar in the Royal College of Surgeons. Elizabeth Jones (UCL STS) explains why it is there and the questions to science that it poses.

Death Drawing

Friday 27 October 6-8pm

Workshop

Grant Museum of Zoology

Be inspired by the heads and art works depicting heads on display in our exhibition, A Study of What it means to be Human?, as well as objects in the Grant Museum of Zoology to draw from death with artist Lucy Lyons. Includes an afterhours visit to the exhibition.

Fake News: The Heads of Jeremy Bentham and Flinders Petrie

Wednesday 22 November 1.10 – 1.50pm

Talk

Octagon Gallery

Everyone knows that the philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s head was used as a football. We all know that the widow of the Egyptian archaeologist Flinders Petrie brought Petrie’s head to England in her hatbox. Yet neither of these stories is true! Find out more about how such myths are made and how this exhibition is debunking these and other ‘fake news’.

Unexpected Utility: Sequencing the Genome of Jeremy Bentham

Wednesday 11 October 1.15-1.45pm

Talk

Octagon

This talk explores what ancient DNA is and how an attempt was made to sequence the genome of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Lucy van Dorp will explain why we bother to analyse ancient DNA and present examples of how such analysis has had an impact on modern understanding of diseases and human activity.

Lost Skills: Will Writing

Tuesday 21 November 1.10 – 1.50pm

Workshop

Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

How do you write a will? How do you make it legally binding? Be inspired by a 3,000-year-old example preserved on papyrus from Ancient Egypt to write your own will. Discover how philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s will had an impact on modern ideas about death. Find out more about these historic examples and get advice on will writing.

Curating Heads: Museum Studies Round Table

Wednesday 22 November 4-5.30pm

Discussion

Institute of Archaeology

Chaired by Dr Alice Stevenson (UCl IoA) a panel of museum professionals who’ve curated human remains and material culture around death and dying give provocations for discussion.

A Wake for Jeremy Bentham: What Jeremy did for Death and the Living

15 February 6-9pm

Late opening

South Cloisters, Wilkins Building

Join us to celebrate Jeremy Bentham’s 270th birthday while his head is on display in the Octagon gallery and to bid adieu to his auto-icon as it goes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. At this long-table style event a series of speakers will make a 5-10 minute ‘toast’ to Jeremy Bentham that explores how his decision for his body to become an auto-icon had an impact on how death and the dead body is perceived as well as people living.

Close

Close