Never before cities have presented a panorama of crisis such as the one we are experienced today in most parts of the globe. Their unstoppable growth in conjunction with the crisis of financial capitalism has given rise to an unstable social and political scenario that is disrupting the established knowledge, practices and values. The context in which planning and architecture discourses and products have been developed in the last years does not exist anymore. We are now navigating throughout a time of indeterminacy and extraordinary complexity in which an important phenomenon is happening: the change in the way we look at things.

Understanding that crises are temporary and that they do have a function, as the scientific philosopher Thomas Kuhn contends, helps to apprehend them. The architect Izaskun Chinchilla, following Kuhn, asserts that innovation is the only solution to the crisis. In the process of getting over it, there is a moment before the production of inventions, that is, before the revolution and the acceptance of new theoretical explanations, when different manners of observing reality prompt discoveries, innovations that still need to be endorsed. In order to validate the changes of paradigms, scientists must re-educate their perception and transform the conceptual world they are referring to. They have to create new narratives and theories to test which ones best represent and contribute to the production of knowledge and, in doing so, crystalize the revolution. To perform this task scientists use aesthetics as a criterion of validation or discrimination (Chincilla, 2013).

In an analogous reflection, the philosopher and activist Fernández-Savater explains in his text Política literal y política literaria (Fernández-Savater, 2012), that at any time that practices of emancipation emerge and question in a radical manner the ways society is organized, new words to define reality and ourselves spring. The potential of fictions, metaphors and stories is essential to foster a new social imagination capable of creating a new noun or collective character that does not exist in the prevailing power structures and does challenge them. The new collective character creates a different space of subjectivation where the previous perceptions, languages and behaviours are displaced and transformed. It disrupts the reality of classifications and identities. “The collective character of the political fiction produces new reality because it redefines the map of the possible: it does not only modify what it is possible to see, do, feel and think about the reality, but also who can do it”. For the philosopher “fiction is the potential of humanization by excellence” (Fernández-Savater, 2012).

In line with these claims, the anthropologist Holston also asserts the need to develop a different social imagination in planning and architecture in order to construct the future of our cities (Holston, 2008). But how can we know that we are not proceeding as Le Corbusier and modernist architects did in 1940? If we are for a revolution, how can we avoid falling again into an ideal model out of context? In the anthropologist´s words: “What kind of intervention in the city could construct a sense of emergence without imposing a teleology that disembodies the present in favour of a utopian difference?” (Holston, 2008). To address these questions Holston vindicates the realm of the ethnographic present as opposed to the utopian futures. “The necessity of having to use what exists to achieve what is imagined” (Holston, 2008), that is, to seek the chances for change in the existing social conditions. He defines spaces of insurgent citizenship as those that interrupt entrenched stories by introducing new identities and practices in cities. Those capable of creating different sources of citizenship rights and defend their legitimacy.

Being personally sympathetic to Holston´s propositions, however, I would like to ask: is the disruption that these spaces of insurgent citizenships trigger, radical enough to construct a truly new social imagination? Can new paradigms and values be envisioned and achieved relaying exclusively on the ethnographic present, that is, on empirical data? Is a notion of contextualized revolution capable of creating a new global order? In this paper, I argue that cities are now living at a time prior to replacement of models akin to the moments of change of scientific paradigms explained by Kuhn and Chinchilla, where there already exists a strong social substrate favourable to try out a radical overturn and open the horizon of the social imagination to a new socio-political constituent process. In this situation of rupture and re-education, as Fernández-Savater and Holston contend, the human capacity for narrative is key for the change.

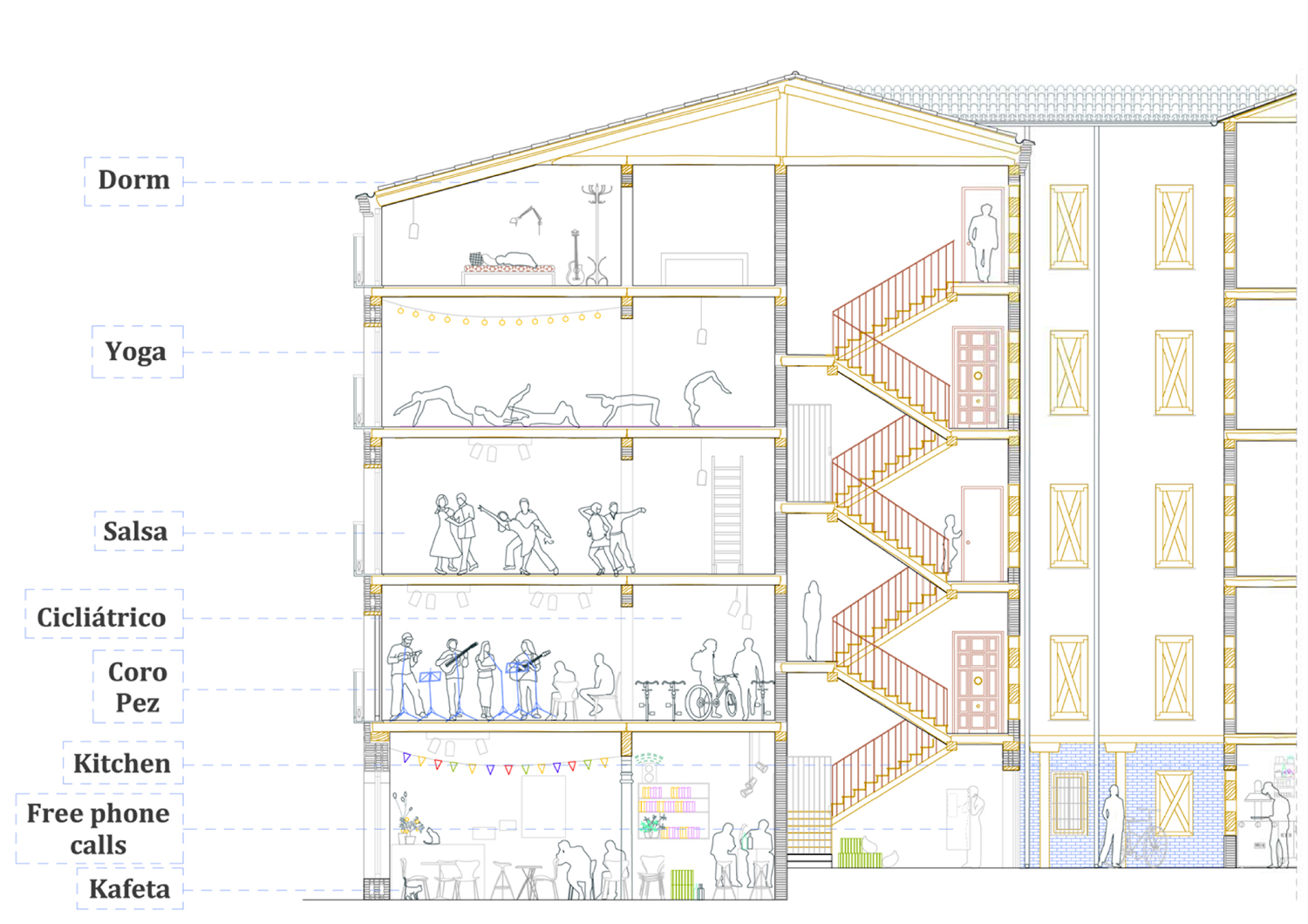

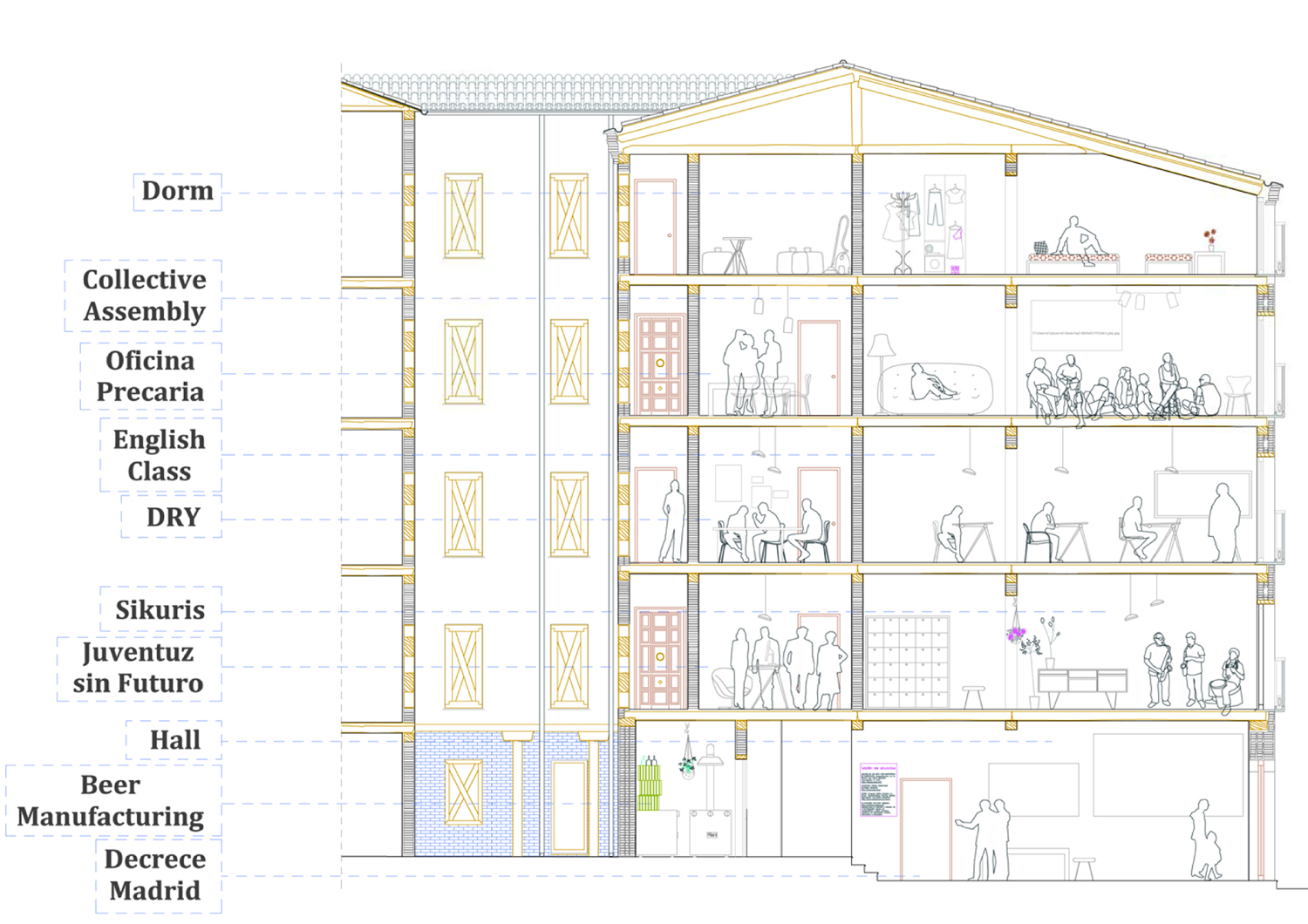

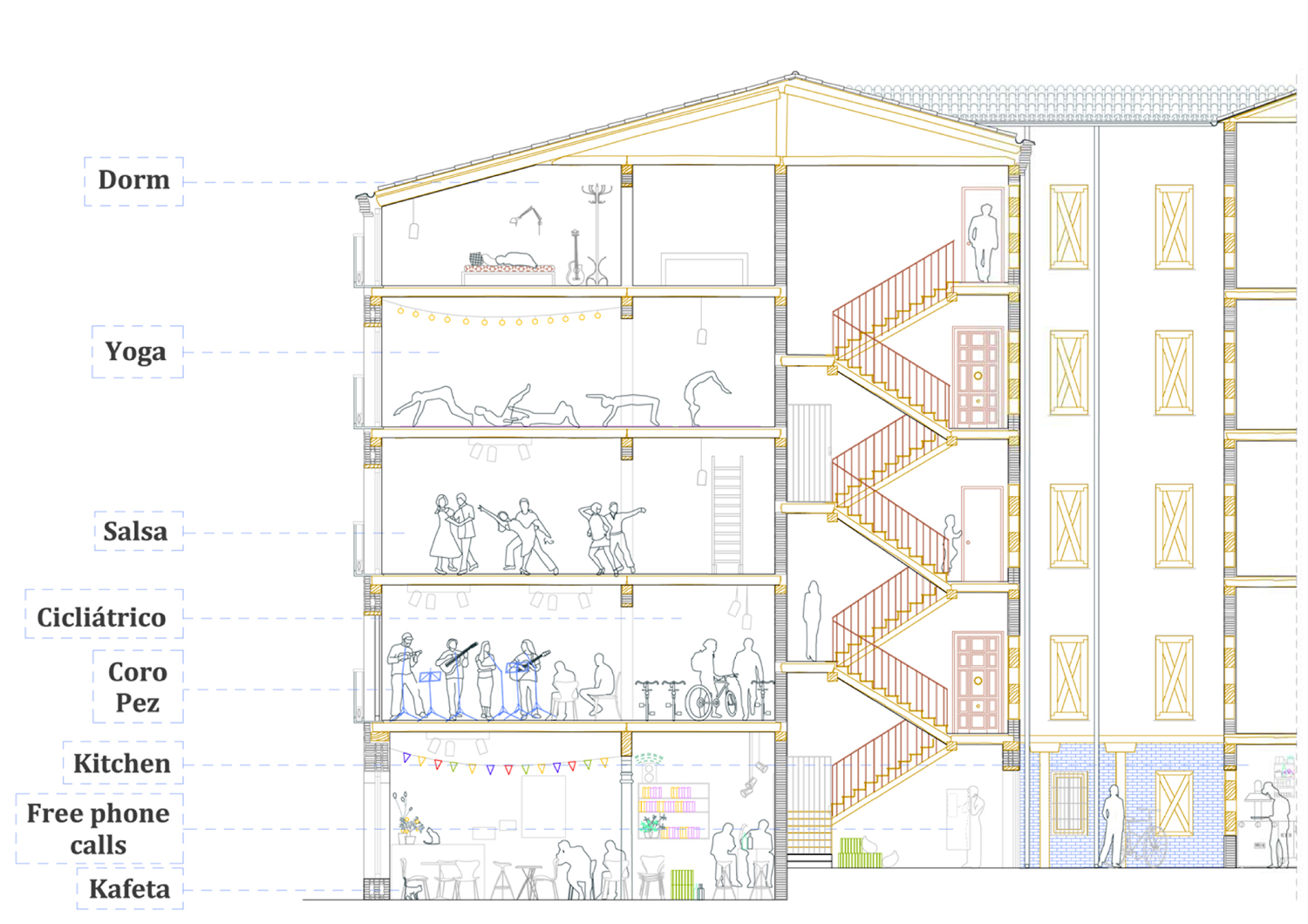

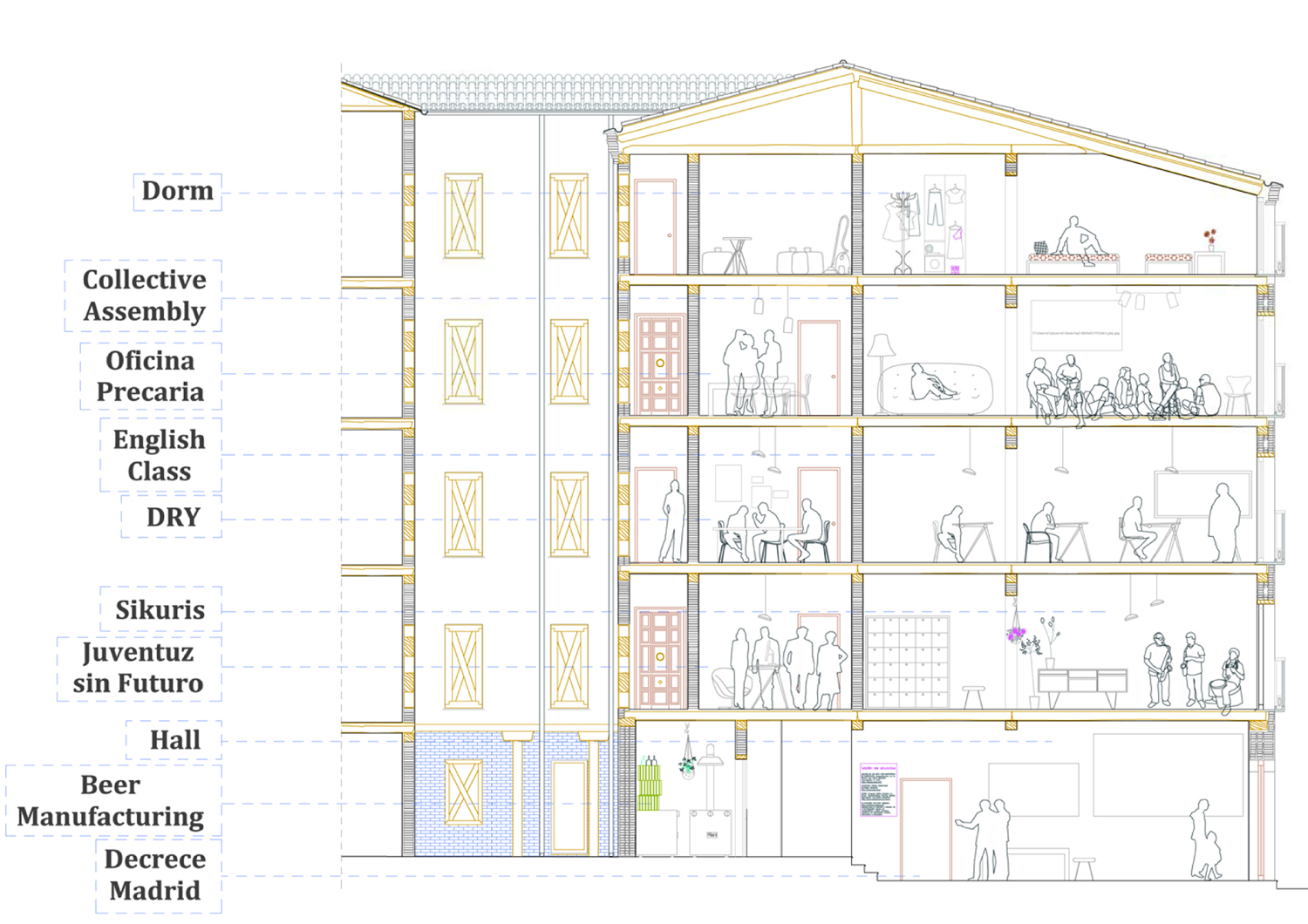

In this essay I will position Holston´s premises for developing a future world´s imagination in dialogue with Chinchilla and Fernández-Savater propositions. To perform this endeavour I will base my observations on an ethnographic study of El Patio Maravillas, a social centre in Madrid, Spain, in danger of eviction. I will focus on the current potential of social centres to foster new imaginaries and in doing so, I hope to glimpse some of the conditions that constitute the signs of contemporary transformations in cities, take the claim for innovation beyond the recognised realms of planning and architecture and pose some questions about widespread change.

The analysis of the case study will be broken down into three main sections, namely A Civic Infrastructure, Disobedient Object(s) and An Insurgent Cities-Network, that can be understood as either different scales of observation or three scopes of intervention of El Patio Maravillas.

LSE