by Sylvia Croese and Yohei Miyauchi

Master plans are making a comeback in Africa. Sometimes these plans translate into entirely new master planned cities, such as Tatu or Kilamba City in the outskirts of Nairobi or Luanda. These plans also translate into urban mega projects involving large scale infrastructural developments. Examples of this include, high end residential and commercial seaside developments in Lagos or Accra, or Bus Rapid or Light Rail Transit systems in cities such as Dar es Salaam or Addis Ababa.

Many scholars have critically written about the modernist ‘world class’ visions of utopian urban futures that underpin these projects. They critically analyse the role of private and transnational consultancy firms and developers in advancing these urban imaginaries, and often assess the Chinese construction workers that work on building these projects.

However, less is known about the plans themselves, their genealogies and the ways in which and by whom they are conceived, financed and implemented. As part of our work on rethinking the evolving purpose and use of master plans, which is part of the wider research project Making Africa Urban: the transcalar politics of large-scale urban development, we have started looking into the role of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in master plans in Africa. JICA is the governmental agency that delivers most of Japanese Official Development Assistance (ODA).

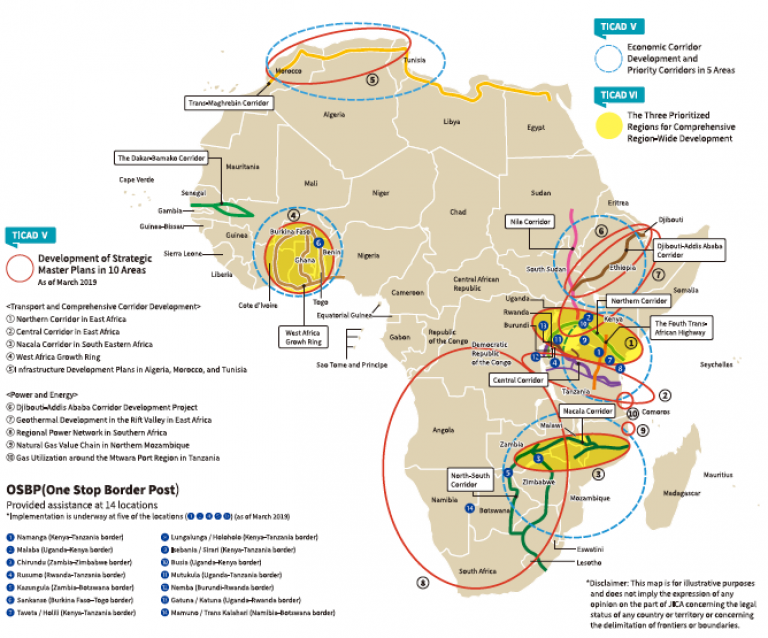

In recent years, JICA has become actively involved in the development of urban master plans in Africa, with a focus on urban transportation and infrastructure planning. This has taken place in cities ranging from Abidjan to Dakar, including Lilongwe, Nairobi and Nouakchott. This involvement builds on a longer history and policy of infrastructure development as a driver for economic growth. A policy which Japan has actively promoted as one of the world’s largest providers of ODA.

Japanese aid to African countries dates back to the 1960s, to countries such as Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda, but has taken on another dimension since the creation of the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) in 1993. Since then, Japanese engagement in Africa has steadily increased. In 2008 the country committed to doubling ODA to Africa to about USD$ 2 billion by 2012. By 2016 commitments had gone up to USD $30 billion, consisting of public and private investment. JICA now counts offices in 30 countries across the continent and since the fifth TICAD in 2013, its work has been heavily focused on urban infrastructure development.

Key to Japanese engagement is its strong multilateral approach and collaboration with other partners and organisations such as the African Development Bank and African Union. Japan is well networked in multilateral institutions as an active member of global leadership forums such as the G7, G8 and G20, and one of the largest contributors to the UN. This allows the active linking of TICAD objectives to global development agendas, such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and now Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). From this perspective, the development of strategic master plans is meant to support sustainable and environmentally friendly urban development.

However, there is also a strong component of self-interest driving Japanese assistance. Most of this assistance consists of loans, rather than grants, with ODA having to benefit Japanese companies as part of Japan’s longest serving (2006-2007 and 2012-2020) Prime Minister’s Shinzo Abe’s economic strategy of “Abenomics”. The launch of the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI) in 2015 adds a geopolitical dimension, as it has been seen as a way to compete with and distinguish itself from China’s infrastructure development strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative developed in 2013.

Since TICAD 6 in 2016, the first TICAD summit to be held in Africa, Japanese involvement has focused on strategic master plans and urban transportation, expanding into region-wide corridor development. This includes the development of power and energy networks, such as gas power plant development in the Nacala Corridor of Mozambique. Japan’s resource needs have been the likely driver of this development, with its scarcity of natural resources such as oil, coal, and indeed gas. These resource scarcities already drove Japan to trade with South Africa during the apartheid regime, while most other countries were boycotting it.

The rise of urban master plans in Africa should be seen in a wider context of long-standing relations and collaborations between Africa and external partners. These relationships can manifest themselves in different ways and areas, but taken together they are part of a complex mix of different actors and interests. As we proceed with our research, we will delve deeper into the different ways and understandings in which these contribute to ‘making Africa urban’.

Close

Close