Chinese Influence in Making Africa Urban at Scale

30 March 2021

Exisiting dynamics and emerging trends

Over the past two decades, the spatial translation of ‘global China’ in Africa has evolved from an emerging phenomenon to an entrenched presence. Next to the commercial footprints of shops and wholesale malls run by migrant-entrepreneurs, the Chinese investment presence is mainly tied to extractive activities (oil & gas), and construction and infrastructure projects, many of which are now in urban environments.

The apparent match between Chinese investment and Africa’s requirements arguably has to do with China’s attempt to deal with over-accumulation and overcapacity domestically, and Africa’s wish to access loans for projects that do not meet the criteria of potential Western and multilateral agencies. Overall, China’s engagement with Africa, - through bilateral dealings, as part of FOCAC (Forum on China-Africa Cooperation), or more broadly within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) - may be understood as a means to shift China’s surplus capital abroad, but there is also China’s need to secure both critical resources and geopolitical support from Africa.

However, the large-scale investment projects, whether dreamed, planned or implemented, also reflect the recipient’s future ambitions and aims for economic growth and territorial reconfiguration. While China’s interests in Africa are extensively debated, the synergizing (and diverging) interests of political elites in Africa have been given less attention. Drawing on specific examples from the three city case studies (Accra, Dar es Salaam and Lilongwe), this brief overview outlines some of current dynamics which suggest both emergence and change in the China-Africa engagement around large investment projects.

However, the large-scale investment projects, whether dreamed, planned or implemented, also reflect the recipient’s future ambitions and aims for economic growth and territorial reconfiguration. While China’s interests in Africa are extensively debated, the synergizing (and diverging) interests of political elites in Africa have been given less attention. Drawing on specific examples from the three city case studies (Accra, Dar es Salaam and Lilongwe), this brief overview outlines some of current dynamics which suggest both emergence and change in the China-Africa engagement around large investment projects.

There is a spatial representation underlying the way these ‘global infrastructure’ projects are conceived. At the macro scale, of course, is the conception of the BRI, a global-scale corridor of investment. Within Africa, there are also ideas of investment corridors at different scales which are organized around the movement of people, goods and information. Within these corridors are nodes, around which infrastructural and other networks converge.

Within the three case study cities, Chinese involvement can be linked to this framing. Whether in Accra or in Dar es Salaam, the port plays an important role as a logistics and transport node connecting to the global economy. Accra’s harbour is located in Tema, about 30 kilometres east of the capital, and serves as a major outlet and commodity transit (handling 85% of Ghana’s trading activities) for landlocked countries to the north of Ghana. Constructed in 1962, the harbour has been undergoing major expansion works since 2016 with the aim of tripling its handling capacity. The project, estimated at a cost of US$ 1.5 billion, has been led by a consortium of the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority (GPHA), and the Meridian Ports Services, with Bolloré Africa Logistics (France) and APM Terminals (the Netherlands) as the latter’s two main stakeholders. The expansion of the port includes a 35-year concession which was already signed in 2004. The majority stated-owned, and Beijing-headquartered China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) won the contract to carry out both the first and second phase of the expansion work. With the first phase completed in June 2019, Tema Port has become the largest of all ports in terms of capacity in West and Central Africa. The financing package has been led by the IFC (part of the World Bank Group) with US$ 667 million, including US$195 million drawn from their own account and US$472 million secured through three commercial banks: Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (in combination with Standard Bank of South Africa), as well as the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO).

It is significant that, in the case of Tema, Chinese participation and interests exist alongside other international stakeholders, both sovereign and private, and that the development cannot simply be labelled as ‘Chinese’. However, Chinese involvement in Tema does represent a growing Chinese interest and participation in ports throughout the continent. According to a recent study by the Center for Strategic & International Studies there are at least 46 sub-Saharan African ports, either existing or planned, which are funded, built, or operated, by Chinese entities, with Chinese investment present in roughly 17 percent of the 172 sub-Saharan African ports listed in the 2017 World Port Index.

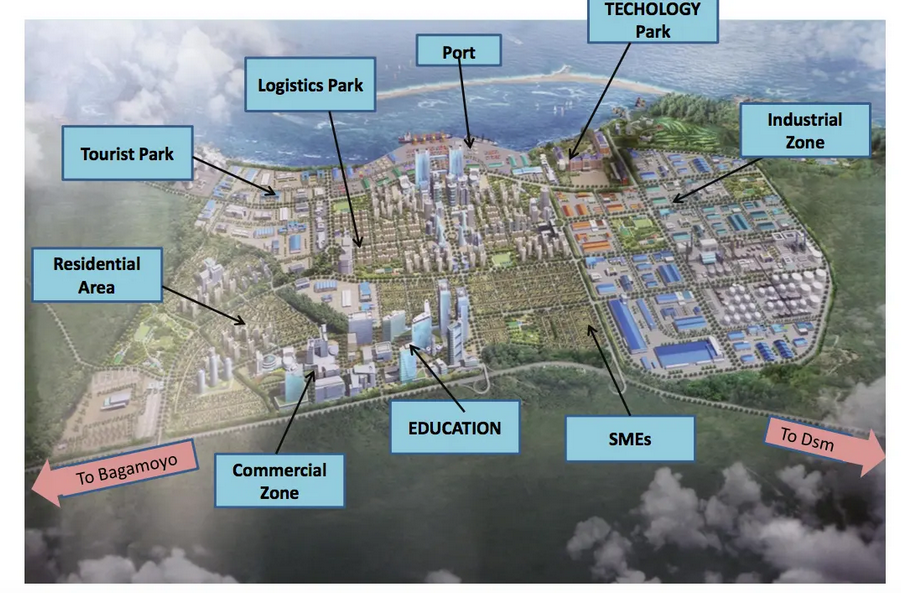

Despite a considerable reliance on foreign funding or expertise to build new ports or upgrade existing ones, these projects, aimed at increasing performance levels, are not only tied to 'contingent circumstances and structural conditions', but also to the complexity and contradictory nature of political effects. This can directly be illustrated by the changing fortunes of Tanzania’s Bagamoyo Port, situated 75 km north of Dar es Salaam, which was to be built and operated by Chinese stakeholders and projected to become the continent’s largest port. From the original conception of a two-berth port in the mid-2000s to the development of the Bagamoyo Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and related seaport, the cost of the project similarly ballooned from US$ 225 million in the mid-2000s to US$ 10 billion when the agreement was signed in 2013. In terms of financing, China Merchants Port Holdings Limited – a partly state-owned Hong Kong-based conglomerate - agreed to cover 80 per cent of the cost, with the Sultanate of Oman’s sovereign wealth fund responsible for the remaining 20 per cent. As one of the flagship projects of the BRI, Bagamoyo was anticipated to become the biggest container terminal in Africa, with a handling capacity of 20 million TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit) by 2045, about 25 times the amount the Dar es Salaam port handles. According to the 2013 Master Plan, the related SEZ would be developed following the requirements for a township SEZ, and set up as a new city equipped with industrial zones, tourist and recreational areas, institutional and administrative facilities, a port and a railway line, as well as a dedicated residential area (able to accommodate a future population of about 75,000 people).

However, with John Magufuli coming to power in November 2015, and reassessing the plans of his predecessor, Jakaya Kikwete, the entire project was suspended. Magafuli, argued that the conditions Kikwete negotiated were equivalent to selling Tanzania to China. In 2019, the government of Tanzania rejected and revised five demands made by the main investor, China Merchants Holdings, as they were considered detrimental to the country. As part of the revised conditions, the 99-year lease was to be reduced to 33 years, the tax holiday and special status of the investor would be scrapped, no other business could be started or run without the government’s approval, and Tanzania would be free to develop other ports, even if potentially in direct competition with Bagamoyo. Since then, the overall project seems to have lost traction, with reports of a subsequent cancellation. Furthermore, Bagamoyo was not mentioned during China’s Prime Minister Wang Yi’s recent visit to Tanzania in January 2021, forming part of the yearly Africa tour to select countries. It points to unpredictability and volatility tied to the slow and multi-phase implementation of large-scale projects, vulnerable to the politicised nature of these undertakings as well as the changing reality of economic conditions and priorities. The confirmation of Magufuli’s passing in March 2021 adds another dimension of uncertainty, with questions regarding the political and economic direction of his successor, Samia Suluhu, both internally and in relation to external partners.

If, during the second decade of the 21st century, the Western narrative shifted (somewhat simplistically) towards portraying Africa as the hopeful continent with rising economic growth rates, more recently there have been growing concerns about an impending debt crisis. The precarious debt burdens of several African nations, epitomised by Zambia’s sovereign default at the end of 2020, has led to greater caution in terms of either taking on or handing out sizeable loans, but also regarding the selection and implementation of specific projects. Economic challenges are not recent, but the current Covid-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these pre-existing economic difficulties. Within the broader landscape of debt, China has over the years become a major creditor of infrastructural projects, raising anxieties about the quantity and sustainability of debt contracted by some African states. At the same time, if China is the largest single creditor for African countries (with around 20 per cent)[1] and loan commitments worth US$ 148 billion from 2000 to 2018, about 35 per cent and 32 per cent of African debt is held by multilateral institutions (e.g. the World Bank) and private lenders respectively. Overall, with less funding available and a higher adversity to risk (whether from investors or recipient countries), the nature of Chinese involvement in large-scale projects might become less predominant or follow a different approach.

As a result of contracted economies and revised priorities, some projects have either been stalled or are being reconsidered while others carry on. Back in 2012, news circulated that state-owned China Airport Civil Construction (CACC) signed a MoU with the Ghanaian Ministry of Transport to undertake a feasibility study for the design of Ghana’s second international airport in Prampram, a coastal town in vicinity of Tema. CACC was set to begin construction in 2013, but in 2020 government was still debating whether to go ahead with the new airport (estimated at a cost of US$ 10-15 billion), or rather increase the capacity of the existing Kotoka International Airport (KIA). In 2017, several potential international investors (including from China) submitted proposals to the Ministry of aviation. With the most suitable to be selected, the airport project (if implemented) would be combined with ancillary components such as housing, light industry, free zones, cargo sections, and hospitals. Plans for a new airport in Prampram date back as far as the 1980s, but until now it has not materialised. In Tanzania, while the outcome of the Bagamoyo project remains unclear, the government signed a deal with China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) to expand and upgrade its main port in Dar es Salaam, marked by growing congestion and inefficiencies. The project is funded through a US$ 345 million loan from the World Bank. Similar to Tema in Ghana, Dar es Salaam’s port handles the bulk (about 95 per cent) of the country’s international trade and serves as a strategic outlet and freight linkage for the neighbouring landlocked countries such as Malawi, Zambia, Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda. At the same time, during Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent visit, Tanzania also signed a US$ 1.3 billion contract with two Chinese companies, China Civil Engineering Construction (CCEC) and China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC), to build a 340 km link from the port of Mwanza on Lake Victoria to the southern town of Isaka. This section forms part of the country’s US$ 6.7 billion new standard gauge railway (SGR) network, which was announced in 2017, and is subdivided into five phases, with the 205 km link between Dar es Salaam and Morogoro (situated halfway between Dar and the capital Dodoma) implemented by a Turkish-Portuguese consortium. Overall, the way in which many of these recent projects unfold, with a growing separation between the different project components, speaks to the growing complexity of Chinese overseas sovereign investments. It also points to a partial shift away from a tendency to control the entire project cycle, characterised by the combined financing, construction, and, sometimes even, management and operation by different Chinese state-owned entities.

Spatially, different patterns have started to emerge. In contrast to China’s long history of bilateral relations with Ghana and Tanzania, Malawi only established official ties with Beijing in 2007, after breaking off its 41-year-old links with Taiwan. In Lilongwe, initially planned as a ‘garden city’, the emergence of Chinese construction projects has started to add new (vertical) features to the layout of the capital. The parliament building, the Bingu national stadium, the Bingu International Convention Centre and adjacent 5-star Umodzi Park Hotel, all funded through bilateral loans, as well as the Golden Peacock Hotel complex developed by the Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group, have all turned into visual landmarks. Next to these government-led initiatives, there are a number of private investments, including an on-going housing project implemented through a joint-venture between the Malawi Housing Corporation and Henan Guoji, a Chinese company which has established a modus operandi of JVs with African government agencies. There is also the Grand Business Park developed by the China Lilongwe Grand Holding Development Corporation which is incorporated in Malawi but with the Shanxi Chuandong Construction Group and Shanxi Changfeng Construction Limited as its two shareholders. Whether intentionally or not, these public- and private-funded Chinese investments follow a corridor cutting across the capital from east to west and then heading towards the south.

Both in Accra and in Dar es Salaam, Chinese investors are often involved in spatially and sectorally related projects. For instance, CHEC’s upgrading of the existing port in Dar es Salaam, in addition to the recent Chinese investment by CCEC and CRCC in a specific segment of the Standard Gauge Railway system speaks to China’s involvement in Tanzania’s ambitions for regional and international connectivity ambition. Adjacent to the new container terminal at Tema port built by CHEC is an export processing free zone and industrial park which hosts six Chinese factories, pointing to a partial clustering of Chinese activities and interests near the port. At the same time, spatial logics in all three urban environments, either clustered or scattered, are tied to a mixture of different and at times overlapping rationales and temporalities. These range from straightforward business decisions, the implementation of projects decided by the host government, to the pursuit of strategic and geopolitical ambitions, whether by China or the host country.

Many of these projects are nested within a particular language of modernity and development on the one hand, and China’s contribution to change in Africa on the other. Prior to the actual construction, planned projects are increasingly captured by digital visualisation and communication processes, as illustrated by the following example about the Grand Business Park in Lilongwe.

[1] According to another source, a 2020 briefing paper by the China Africa Research Initiative, the overall figure is estimated at less than 15 per cent of the debt stock. However, data released by the World Bank (in June 2020) indicated that seven countries were at risk or already in debt distress: Djibouti (57 per cent), Angola (49 per cent), the Republic of Congo (45 per cent), Cameroon (32 per cent), Ethiopia (32 per cent), Kenya (27 per cent) and Zambia (26 per cent).

Fig. 1. Ghanaian stamps referring to the opening of the Tema Harbour and the adjacent new town in 1962.

Fig. 2. Outline of the projected Bagamoyo Special Economic Zone (Source: EPZA Tanzania).

Close

Close