Windrush Cricket project captures the stories of east London’s Caribbean cricket clubs

22 June 2021

In this blog, Dr Michael Collins, Associate Professor at UCL History, explains the role of cricket in the experiences of the ‘Windrush generation’ and how a UCL East funded project has helped to record these stories.

As the project expands to cover all of London and a host of other cities in England, Dr Collins is keen to hear from anyone with relevant experiences. Please contact Dr Collins directly at michael.collins@ucl.ac.uk for more information.

The Windrush Cricket Project is a social and cultural history of Caribbean cricket, in England, told from the perspective of everyday lived experience. It is an attempt to understand how cricket was an important part, possibly an integral part, of a process of Caribbean migration and settlement in England after World War II.

Research started in June 2020 in east London and is now expanding to include the whole of London, as well as Caribbean clubs and communities in Bristol, Nottingham, Leicester, Leeds, Sheffield, and Manchester, drawing on a much wider range of oral histories.

People brought cricket cultures with them as they migrated. Of course, those cricket cultures were originally exported through colonialism. But they were adopted, adapted, and localised in the Caribbean in different islands. When people moved to England, they brought these localised cricket cultures with them.

There are many different dimensions to the experiences of people in these communities, which were very much shaped by class. When people started to move to the UK after 1945, some of the early migrants were middle and upper middle class – aspirational, often students with ambitions to work in professions – and coming from elite schools in the Caribbean, particularly Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad; they were already part of a kind of network of what we might call ‘colonial culture’.

When these people arrived, they typically played cricket at quite a high level and moved in cricket circles that were equally as affluent and middle class. This was particularly so in the southeast of England. One thing to remember is that cricket was a much bigger social phenomenon in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s than it is now –large companies would often have multiple cricket teams.

For example, London Transport was a massive hub for cricket. Such corporations and organisations had great facilities and owned a lot of land, and this became part of the recruitment strategy. Cricket was frequently mentioned to potential migrants and workers as an attraction and enticement.

Many of those interviewed so far who have the earliest memories of playing cricket in the 1950s in these professional and corporate circles often reported positive experiences, or an absence of overt racism. It is possible that the white English people interacted with believed that the black Caribbean cricketers they played with remained firmly part of an imperial framework, and that they would soon return to the Caribbean.

However, there is a different side to the story. While many of those who came to the UK in the so-called ‘Windrush generation’ were highly educated, many of them arrived to perform what we might term as working-class jobs. These people were often seen as longer-term settlers and experienced much more overt racism and exclusion from existing cricket clubs.

It is for this reason that many of them set up their own clubs. We start to see the earliest Caribbean cricket clubs in England from about 1948, the first being Leeds Caribbean. One of the early clubs in London is called Carnegie CC, which was started up in the Brixton area.

These were interesting developments because they were reactions to overt racism, but they also constituted commitments to build social spaces that could sustain longer term migration and settlement.

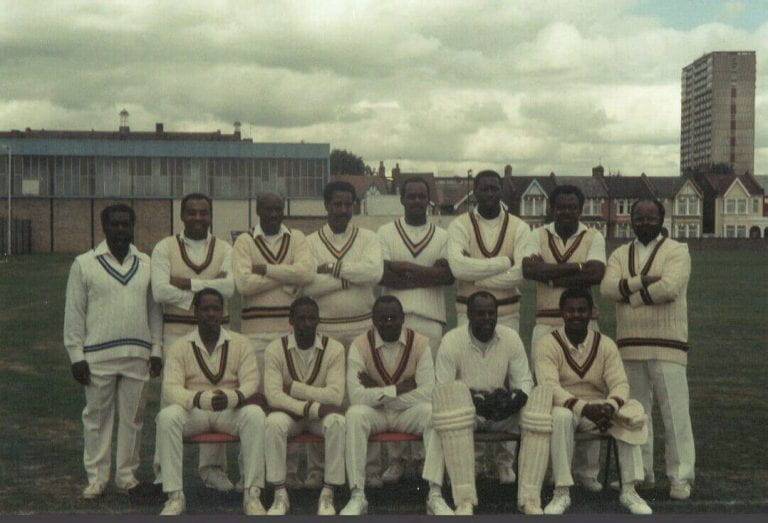

From the 1950s there was then the growth of a whole ecosystem of Caribbean cricket in England. By the 1970s, this had become a huge phenomenon – there were literally hundreds of Caribbean cricket clubs playing across England, to a very high standard. However, this was happening outside the purview of the Test and County Cricket Board and the power structures of English cricket.

The Windrush cricket generation speaks to the experience of racism in urban environments, but also opens further questions due to the nature of cricket as a game where you often travel long distances to play a fixture in rural locations.

Consequently, it also creates interfaces between urban migration and rural social and cultural life. There were a lot of trips from east London to places such as Kent and rural Essex, and for many of these people, that was their main experience of white, English society. It was an important contact zone, in that sense.

Furthermore, it was not always hostile – there are many stories of games being very friendly affairs in which people were welcomed. In addition, cricket is quite a public sport – it was played at lunchtime in parks or at the centre of villages, without the terracing and gating of other sports such as football.

Several of the people, especially women, I have interviewed have said that their early childhood memories were of playing around the boundary and spending a whole day relaxing by the side of a cricket pitch, and that this was quite memorable because relatively unusual; in their everyday urban lives there was sometimes a more menacing atmosphere.

This does not in any way downplay the existence of overt racism within metropolitan English society, but it does mean that the story of cricket for the Windrush generation is a rich and diverse one about migration and the interface between Caribbean communities and a majority-white society.

But by the 1980s and 1990s, it also became a much more political story where the authorities and power structures of English cricket at the national level started to confront the rise of the ‘black cricketer’, in very problematic ways. These issues speak not just to the experiences of migration from the migrant and settler perspective, but also to the problems of being admitted into an ethno-national community and the ways in which class, power and politics shape ‘majority reactions’ to incoming migrant communities.

In terms of the Windrush Cricket Project and methods, we have collected oral history testimonies of those from the Windrush generation involved in black Caribbean cricket clubs. There are many subtleties to these stories, which are not accessible through any kind of archival research, which makes interviews and discussions valuable.

Many interviewees have commented that these stories only exist as memories and as spoken words, partly because many of these clubs were relatively informal, without club records; as such it is often deemed important by the interviewees themselves to record these experiences as a form of cultural memory.

We are still in the process of collecting oral testimonies and would be delighted to hear from anybody who has any memories or experiences of cricket, not just those who played but also anyone who was involved in organising, attending, or travelling to the games. We are looking for people from the ‘Windrush generation’, which is people who arrived, or whose parents arrived, to the UK in from 1950-1970. Even if you hated cricket, we are keen to hear that story!

Close

Close