Call for Papers: 1989's Loose Ends

17 May 2019

Invitation to submit proposals for the SSEES Conference '1989's Loose Ends'

It was not Tiananmen Square, the Yugoslav Wars, Fujimorism, the Rwandan Genocide, the Chechen wars, the Middle-Eastern conflicts. It was not 9/11, the Invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, the rise of authoritarian capitalism in China; it wasn't even Putin's ascent, the global financial crisis of 2008, or the ineptly named ‘European migrant crisis.’ For almost thirty years, regardless of the conflict of the moment, Francis Fukuyama continued to maintain that his much maligned ‘End of History’ thesis, which announced the ‘victory of the West, of the Western idea’ (1989) as the final, perfect form of governance, was merely being delayed. Even Donald Trump’s electoral victory did not convince him to the contrary, but it was in reaction to it that Fukuyama’s typical talking points started to take uncharacteristic turns. The ‘liberal elites,’ he wrote (The Financial Times, 2016), must start addressing the issues of equality and identity, the two key factors that drive the democratic legitimisation of anti-liberalism, and the very cradles of Western-style democracy, the US, the UK and European countries, must be particularly cautious in this respect. For if populist nationalism prevails in the West, the ‘global liberal order’ would collapse – and that, in Fukuyama’s own words, would mark ‘as momentous a juncture as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.’

Among the myriad of ironies evoked by this warning, perhaps the most telling one is that on the other side of the Berlin Wall the aftermath of 1989 was often represented as a period when the victory of liberalism and the homespun demise of liberalism peacefully coincided. In Jáchym Topol’s novel Sister (1994), for example, the Velvet Revolution brought in thousands of abandoned Trabants that started clogging up streets outside of Prague’s embassies, as well as unexpected ‘byznys’ opportunities for the main character, who made a fortune by peddling globalised kitsch such as ‘Ukrainian-Vietnamese-Laotian-Czech samurai swords.’ The local and the global, the end of the history and its rebirth, the formal, the archaic and the vulgar, were here all superimposed onto one another, forming what the literary scholar Peter Zusi called ‘coherent incoherence: the story embodies paradox, but the image holds true.’ In this view, the discourse of Posthistoire – a mid-19th-century concept that came to be intimately intertwined with both 1989 and postmodernism – did not necessarily announce the end of an ideological era, but rather revitalised the long-standing crisis of narratability (‘History’s Loose Ends,’ 2012).

If this crisis allows us to draw affinities between the strangest of bedfellows, then where else, globally, can we observe 1989’s loose ends? On its 30th-anniversary, we invite papers that challenge the understanding of 1989 as a fundamentally Cold War, Eurocentric event with established historicity and geography. How might we address the impact of 1989 on art, history, literature, culture and philosophy and how do these, in turn, inform our understanding of this event? And how might we observe these loose ends in a way that does not merely look back to the ‘good old days,’ but addresses also the bad new ones?

Scholars from all disciplines are invited to submit proposals for 30-minute presentations. Please send a title, abstract (300 words maximum), and short biography (approximately 100 words) to SSEES-Events@ucl.ac.uk. by 31 July 2019. There are a limited number of travel bursaries available for those living outside London. If you would like to apply, please contact the organisers.

This conference is due to take place on the 7th and 8th November.

This event has been made possible through the support of the Leverhulme Trust, The FRINGE Centre for the Study of Social and Cultural Complexity, and UCL’s Octagon Small Grants Fund.

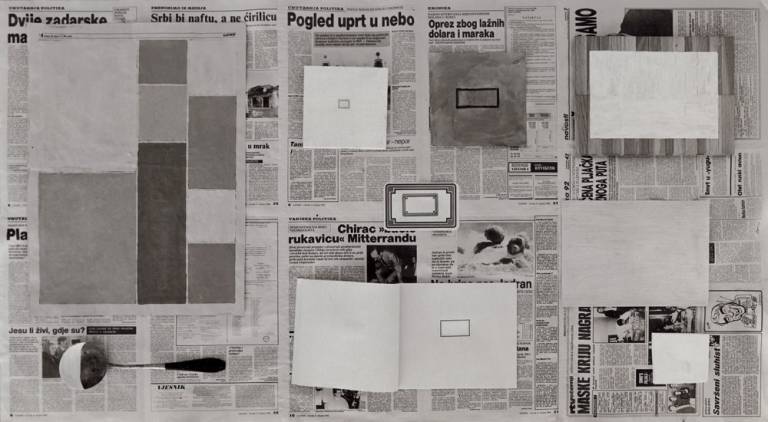

Image: Mladen Stilinović, Geometry of Time, 1993-1977, 1993. Photographed by Boris Cvjetanović. Image permission courtesy of Branka Štipančić.

Close

Close