Rest in Pegabytes

Jesse Giordano

click ↑

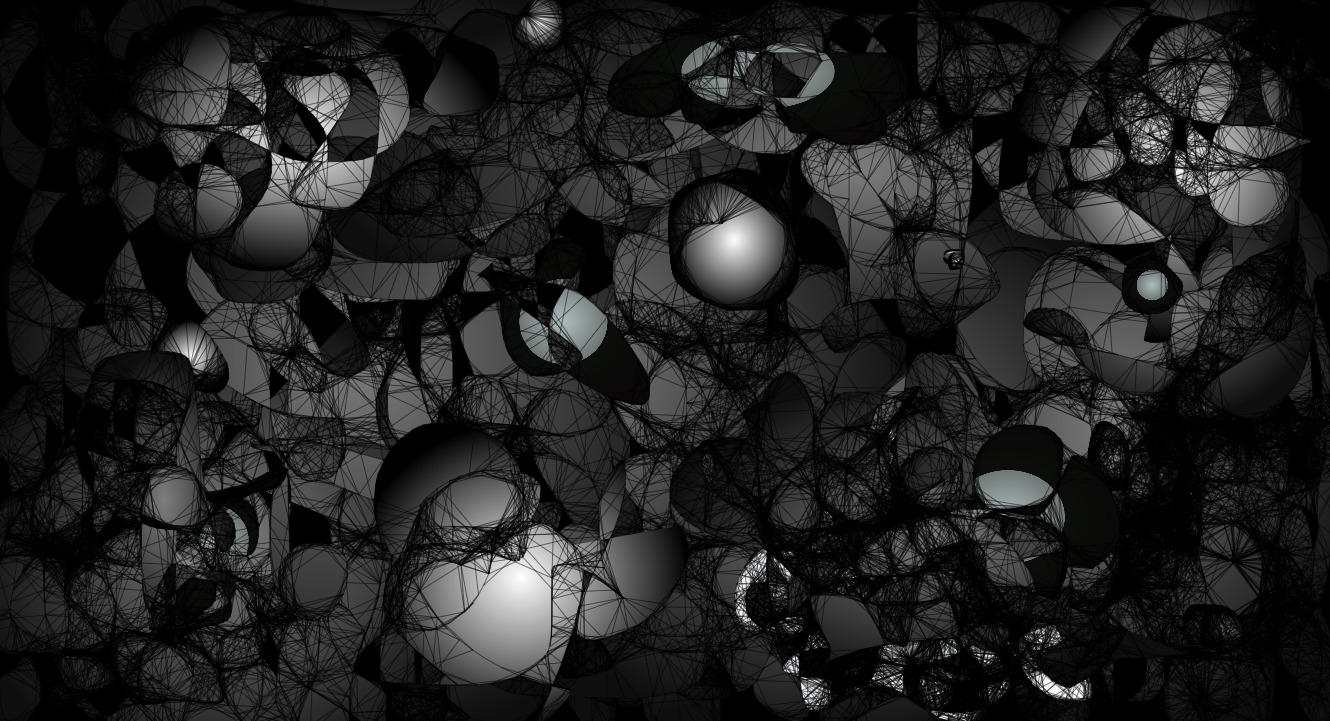

This piece is the portrayal of the digital infrastructure of online cemeteries that have become a recent trend in the veneration of deceased loved ones.

During the 19th century, the modern process of embalming a recently deceased body emerged from the American Civil War. Dead soldiers needed to be shipped back home to their loved ones for proper burial but would inevitably decay on the long journey home. Dr. Thomas Holmes invented a solution containing arsenic that effectively killed the microorganisms responsible for the rapid decay of a recently deceased body (Chiapelli 24, 2008), and soon after embalming was used for the transport of dead American soldiers for ceremonial burial. After the war had ended, embalmers found that their business had slowed and in an attempt to keep profits flowing, had convinced the general public that the process of embalming was an essential, sanitary, and proper way to prepare the recently deceased for a funeral ceremony. The process of embalming the body is now a significant contribution to the profits of the funeral industry in the United States which is estimated to be worth $20 million dollars annually (Marks, 2021). The commodification of death is embedded in a wider social context, and “creates ‘moral boundaries’ around the proper preparation and management of death change in relation to economies of service provision and consumption” (Arnold, et al. 102, 2017). Though the embalming process still constitutes a vital step in western funeral burial and especially open-casket ceremonies, different ways of venerating the dead have arisen with the continual shift of our values, the organization of society, and ever-growing technological innovations. In 1995, the World Wide Cemetery’s online memorial site was the first and earliest of its kind to house the recently deceased in a digital resting place. There has been a recent shift to the digitization of cemeteries, from Danish and Austrian QR codes placed on tombstones, Japanese burial urns that light up upon digital recognition, and German graveyard apps, that claim to be a more sustainable, modern route to the future relationships between the deceased and mourning practices (Landsberg 2018). The art piece I have chosen to display is the depiction of digital infrastructure of online memorial sites to analyze the ways that their digitization creates new moral boundaries, new ways of imagining immortalization, and new channels for commodification in the death care industry.

The digitization of memorials and funerals has sparked new entrepreneurial ventures in ‘death tech’, an industry that provides a range of services from pre-planning your own death, to securing your “digital assets” (emails, social media pages, online accounts) after you die. Navigating the western processes of memorializing and honoring a recently deceased person through a proper funeral was always mediated by the companies involved who made some kind of profit from hosting the event, providing the tools necessary for burial, and creating a space for communal mourning. The unique ability of digital cemeteries to “play an important commercial role enabling the businesses to engage with the customer at particular opportune moments, reinforces the presence of the company and its brand in the mind of the consumer” (Arnold, et al. 106, 2017). While most relationships between the consumer and the funeral company end once the ceremony of burial or cremation is completed, the digitization of such practices allows for the funeral home to further implement itself, on a marketing level, to keep in touch with a previous customer through what Arnold et al. (2017) describes as ‘push notifications’. In an interview with an online memorial provider for his book Death and Digital Media, Michael Arnold et. al is told that when a family member adds a message to the platform, “a message is sent to the subscribers to the site notifying them of the post, and of course the notification message is branded with the company logo” (Arnold, et al. 106, 2017). Digital memorial sites can act as an infrastructural trap that preys on a vulnerable population in bereavement by pulling them into a ‘product funnel’ (Seaver 424, 2018) that conflates their communal grief with loved ones on the digital with the covert commercial opportunism from the site that serves as the platform through which this socialization occurs.

An important quality of infrastructures is their ability to warp the perception of time, and in the case of virtual cemeteries, the perception of immortality. The rhetoric surrounding the benefits of digital memorialization is often marketed as the immortalization of a loved one through the creation of an online site or webpage dedicated to them. As long as the digital infrastructure or platform exists, then the recently deceased can live forever in their bits of code and kilobytes. Memory can actively be created on memorial sites and communally shared through the process of uploaded photos and videos. Though it is beyond the scope of this exhibit, this idea of sharing personal data of the deceased brings up the question of postmortal rights, the politics of memory, and how the prevalence of other digital infrastructures like social media make it impossible to forget.

The social implications of digital cemeteries give us new ways of imagining death and navigating the process of preparing for mourning. Perhaps we can imagine the digital immortalization of the deceased as the new embalming invention of the 21st century where we re-define the commodified moral and aesthetic qualities we value when it comes to proper and respectable death preparation. As a digital infrastructure, virtual cemeteries offer new channels for altering the perception of time as being the medium through which the deceased can live on, while also creating a taut grip between consumer and business on the basis of this temporality and moral duty to immortalize your loved one.

References

Arnold, M., Gibbs, M., Kohn, T., Meese, J., & Nansen, B. (2017). Death and Digital Media (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315688749

Capponi, Caroline. “Digitization In Deathcare.” Forbes. (April 2021). https://www.forbes.com/sites/columbiabusinessschool/2021/04/29/digitization-in-deathcare/?sh= 296a2f3f464c

Chiappelli, Jeremiah, and Ted Chiappelli. “Drinking Grandma: The Problem of Embalming.” Journal of Environmental Health 71, no. 5 (2008): 24–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26327817

Landsberg, Torsten. “Cemeteries join the digital app age.” DW. (November 2018). https://p.dw.com/p/38tud

Marks, Gene. “Funerals are expensive. And family firms are under threat from new tech.” The Guardian. (August 2021). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/aug/22/funerals-us-small-business-family-firms

Seaver, Nick. “Captivating Algorithms: Recommender Systems as Traps.” Journal of Material Culture 24, no. 4 (December 2019): 421–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518820366