Brain hand 'map' maintained for decades in amputees

5 February 2019

The brain stores detailed information of a missing hand decades after amputation, regardless of whether amputees still experience phantom hand sensations, finds a new study co-led by UCL.

The new eLife study, conducted alongside researchers at the University of Oxford, revealed detailed hand information in the brains of amputees compared with people who had been born with a missing hand.

The research could pave the way for the development of next-generation neuroprosthetics—prosthetic limbs that tap into the brain's control centre.

"Our previous findings demonstrated the stability of the hand picture in the cortex despite decades of amputation," said first author PhD student Daan Wesselink (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and University of Oxford).

"However, we didn't know whether this hand representation in the brain reflects phantom sensations and therefore only persists in those few people who experience vivid sensations."

The findings build on the team's previous work where they used an ultra-high-power MRI scanner to look at the brain activity of two people who had lost their left hand through amputation between two and three decades ago. Although there was less brain activity related to the fingers of the left hand, they found that the specific patterns making up the composition of the hand picture in the brain were well matched to those of two-handed people.

For their latest study, they used a brain-decoding technique based on the pattern of brain activity in 18 amputees, who lost their hand to amputation on average 18 years ago and experience varying vividness of phantom sensations.

The team also looked at whether development of the hand's neural fingerprints requires some prior experience of having a hand, by studying 13 people who were missing one hand from birth. They asked both groups to 'move' the fingers of their missing and intact hands while in an MRI scanner, and compared the results to two-handed participants.

They found that the brain activity of amputees who had the strongest sensations of being able to move each of their phantom fingers retained the clearest information of their missing hand in their brain.

But even those who barely experience phantom hand sensations had the same information preserved in their brains, which was surprising because those amputees have no experiences during their daily life suggesting that their brain has held on to this information about their former limb.

By contrast, the group born with one hand showed some brain activity during phantom limb movement, but did not have the same neural fingerprint dedicated to their missing hand. This suggests it could be more challenging to design neuroprostheses or perform hand transplants for this group.

“We’ve shown that once the hand ‘picture’ in the brain is formed, it is generally unlikely to change, despite years of amputation and irrespective of the vividness of phantom sensations,” said senior author Dr Tamar Makin (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience).

“Our work suggests that daily life experience could shape the fine-grained aspects of hand representation, but that the large-scale functional organisation of the hand area is fundamentally stable.”

The study was funded by Wellcome and the Royal Society.

Links

- Research paper in eLife

- Dr Tamar Makin's academic profile

- Plasticity lab at UCL

- UCL Insitute of Cognitive Neuroscience

Image

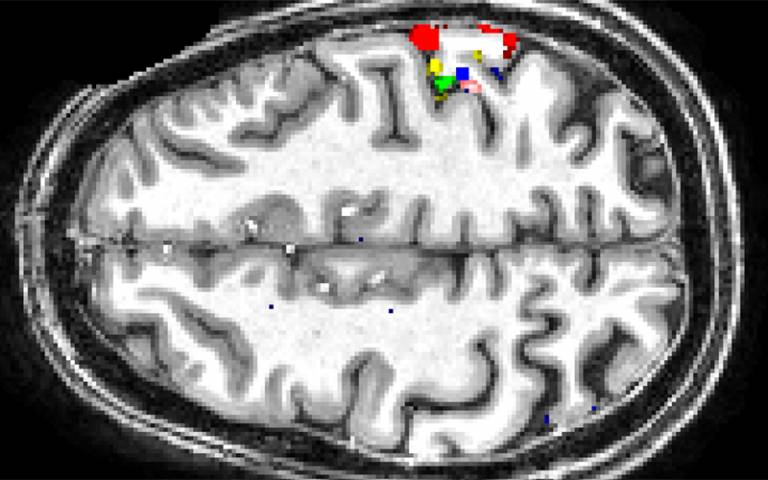

- MRI scan with 'hand area' highlighted in the brain. (Image courtesy Daan Wesselink)

Source

Media contact

Chris Lane

Tel: +44 (0)20 7679 9222

Email: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close