The Palace Scribe: running the state archives of Assyria

Assyrian palaces teemed with scribes who worked with cuneiform and sometimes also with other scripts, most importantly the Aramaic alphabet. But there was only ever one "Palace Scribe" (ṭupšar ēkalli) in Assyria. He was in charge of the state archives and was one of the king's most trusted officials.

In charge of the king's correspondence

Our main sources for the activities of the Palace Scribe date to the 8th and 7th centuries BC and originate from Kalhu and Nineveh. More than anything else, the duties of the Palace Scribe were managerial and consisted of the practical matters of administration and supervision. Even when concerned with ceremonial or ritual affairs, his role consisted purely of arranging practicalities, in stark contrast to the "Chief Scribe" who was the king's chief scholar and his main adviser in all learned matters.

The Palace Scribe managed the state archives of Assyria and organised the written communication and documentation of king, palace and state. To this end, he had to be well informed on all matters of state and his numerous subordinates assisted him in this task. They included a deputy, a great many scribes and a personal chariot team for fast and easy travel across the empire.

The Palace Scribe maintained the correspondence of the king and, at least intermittently and in matters of great importance, acted as the king's personal and confidential scribe and secretary. When making important appointments in the palace, the king valued the Palace Scribe's opinions and solicited his views on the candidates before making decisions. On occasion, the king authorised him to act on his behalf in legal and business matters. Hence Nabu-kabti-ahhešu, the Palace Scribe of Sargon II (721-705 BC), purchased some of the land on which the new royal city of Dur-Šarruken was to be built (SAA 6 31). The Palace Scribe also collaborated closely with the Treasurer (masennu) who held a key role in administrating the state finances. These two officials can be described as the highest-ranking bureaucrats of Assyria's civil administration.

A man of influence

The Palace Scribe's position at the top of the state chancery gave him great power, as emerges clearly from the surviving state correspondence. Eight letters are directly addressed to the Palace Scribe and shed light on his position in the bureaucracy, although they do not mention his name, as was the Assyrian custom whenever the title alone sufficed to identify the individual. They may well refer to several holders of the office: currently, we can identify nine Palace Scribes by name in the period from the early 8th century to the end of the 7th century BC, but there must have been several additional office holders during that time.

Some of these letters are petitions, highlighting the influence the Palace Scribe wielded with the king and within the state. His high status is also clear from the fact that other officials addressed him as "my lord" and used a deferential tone, not too different from the language used in letters to the king himself. The Palace Scribe was one of most influential officials in the Assyrian empire and he could make or break a man. This is especially clear from a letter by a former protégé of the Palace Scribe to king Esarhaddon (680-669 BC), in which the writer is keen to play down the Palace Scribe's power over his actions but in trying to assert his independence achieves quite the opposite impression:

"Would the patronage of the palace scribe have had such an influence over me that I would still be obliged to him? (No), I shall tell to the king, my lord, the thing that I have seen and heard." (SAA 16 78)

The Palace Scribe's important position within the state bureaucracy and his loyalty to the king did not go without material rewards: he had his own village manager to manage his property portfolio. We are best informed about the personal wealth of Nabu-tuklatu'a, Palace Scribe at the beginning of the 8th century BC, some of whose private legal documents were excavated at Kalhu. They document his purchases of a house, part of an outbuilding and two gardens, as well as several slaves. The Palace Scribe was also entitled to a share in the tribute and gifts sent by vassal rulers to the Assyrian king. Hence, a list from the reign of Sargon (SAA 1 34) shows the Palace Scribe (in all likelihood Nabu-kabti-ahhešu) receiving a sum of silver as well as a precious garment and two scrolls of papyrus out of a shipment from Sargon's western allies.

The language of royal power

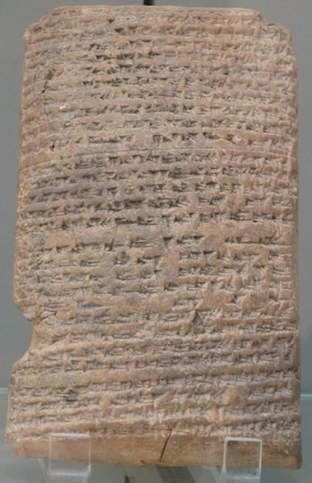

The palace was the main seat of political power and administration and a hub for the king's interaction with his subjects. A key tool in communicating with and controlling the officials governing as the king's representatives all over the empire was the sending out of "the king's word" (abat šarri), as royal letters are called in Assyrian. Some of these letters survive in the royal archives, presumably as copies of the originals that were sent out (e.g. from the reign of Sargon: SAA 1 1, 26; SAA 1 2-25, 27; SAA 17 1-6).

The absolute authority of these royal missives is reflected in the way in which recipients refer to them: "They ordered me/wrote to me from the palace". This is the work of the Palace Scribe and his staff. They issued "the king's word" in a formal, concise manner, using a very specific language that was designed to leave no room for misunderstandings. This style of writing renders a royal letter instantly recognisable, even if only a small fragment of it survives. The successive generations of Palace Scribes were the creators and guardians of this language of Assyrian royal power.

Further reading:

Luukko, 'The administrative roles of the "Chief Scribe" and the "Palace Scribe" in the Neo-Assyrian period', 2007.

Luukko, 'On standardisation and variation in the introductory formulae of Neo-Assyrian letters', 2012.

Content last modified: 30 Jan 2013.

Mikko Luukko

Mikko Luukko, 'The Palace Scribe: running the state archives of Assyria', Assyrian empire builders, University College London, 2013 [http://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/governors/thepalacescribe/]