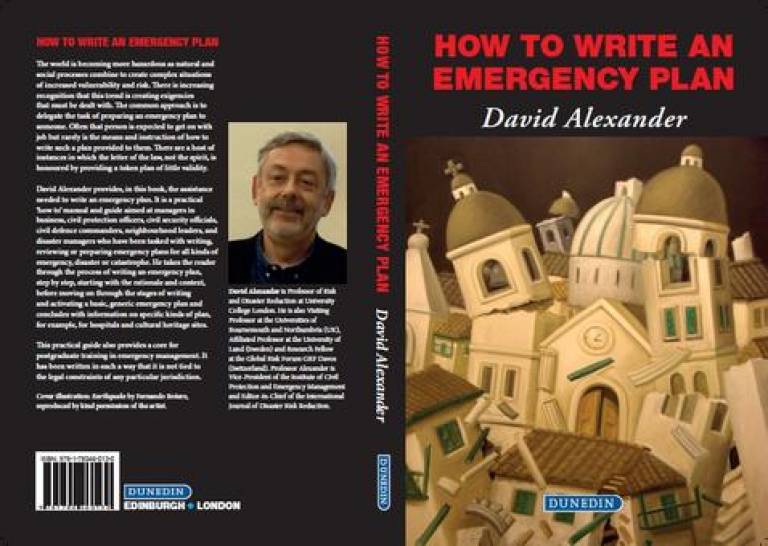

How to Write an Emergency Plan, by David Alexander, published in June 2016

1 August 2016

On 2nd June 2016 Dunedin Academic Press of Edinburgh and London published a new book by UCL-IRDR's Professor David Alexander.

The title is How to Write an Emergency Plan.

The title is How to Write an Emergency Plan.

Some years ago, David Alexander published a book entitled Principles of Emergency Planning and Management (Terra Publishing, Harpenden, and Oxford University Press, New York, 2002). The rationale of concentrating on principles was to decouple the narrative from particular systems of emergency management. For example, American books on managing disasters are so heavily based on US institutions and procedures that this limits their value to emergency managers in other countries. Principles was a success, but feedback from users of the book suggested that they would welcome a practical manual which explains exactly how to plan for an emergency.

Many potential readers of such books have little or no training and experience of preparing for major incidents, disasters and crises. Commonly, they are thrust into the role of emergency planner and left to fend for themselves. Hence, the main purpose of the new book is to take such people through the process of researching, preparing, writing and using an emergency plan. The 'bedrock' level at which this is done is that of municipal government (at every scale from hamlets and villages to city-regions). However, emergency plans are also needed in the health service, airports, industries, commercial concerns, museums and archives and prisons.

The first three chapters of the book explain the emergency planning environment and the nature of an emergency plan. Chapters 5 to 9 take the reader through the steps involved in preparing a basic emergency plan. Chapter 10 deals with a parallel form of contingency planning: that which enables organisations to maintain their normal activities when crises occur, while at the same time they are responding using their emergency plans. The eleventh chapter is the longest in the book and it deals with the specialised emergency planning, including plans to deal with pandemics, nuclear radiation releases, terrorist outrages and post-disaster recovery. The twelfth and final chapter looks into the future of emergency planning. A glossary and bibliography conclude the book.

In preparing for emergencies, it is axiomatic that it is not so much the plan that counts, but the process of planning. It is a learning process: about hazards and emergencies, about resources and competencies, and about the ability of organisations, populations and administrations to cope during crises. Hence, emergency planning is much more than the plan itself. The field is extraordinarily broad and one of its most fascinating aspects is the ability of the diligent planner to discover exactly what can happen during an emergency. There are many surprises, but good scenario-building can, not only form a solid basis for a plan to manage an adverse event, but also reveal where the vulnerabilities lie in society. Many of them are far from obvious, but it is often the hidden weaknesses that become the serious problems in emergency situations, unless they are anticipated by thorough planning.

How to Write an Emergency Plan can be purchased from Dunedin Academic Press or from Amazon. Professor Alexander's other recent book Recovery from Disaster (2015, written with Professor Ian Davis) can also be purchased from Amazon or Routledge Publishers.

Close

Close