Walk information

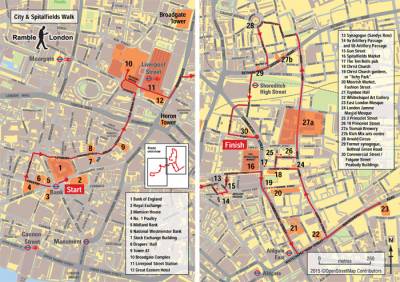

The walk starts at Bank station (Cheapside exit) and finishes at Liverpool Street Station.

How to get to Bank station:

· The Underground lines stopping in Bank are: Central line/Northern line/ Waterloo & City line, and DLR

· Buses stopping in the area: 8, 11, 23, 26, 133, 242, 388, 25, 21, 43, 141

· For more detailed information see Transport for London website

Duration of the walk: 3 hours

Length of the walk: 6.5 km/ 4 miles

This walk should be accompanied with the walk map for a better understanding of the route and locations.

Walk

Introduction

These notes are designed to accompany a self-guided walking tour of the City of London and Spitalfields where, within a few hundred yards, you pass from the financial and commercial centre of Britain into a low-income, ethnically mixed, inner-city area. The walk deals with the following issues: (1) Contrasts between central and inner city; (2) Redevelopment, conservation and gentrification; and (3) Ethnic and racial change.

The walk exemplifies the impact of national and international changes on particular localities; it allows you to explore the changing social and economic geography of the city; and it encourages you to use your powers of observation to try to understand the urban environment. The walk concentrates on four main areas: City of London, Spitalfields, Brick Lane and the Boundary Street Estate.

The Route

Leave Bank station via Cheapside exit. Look at the number of monumental buildings around Bank intersection including the Bank of England [1], the Royal Exchange [2], and Mansion House [3].

Consider the planning history of No. 1 Poultry [4], now the site of a postmodern building, designed by James Stirling, completed in 1998. This superseded a Victorian commercial block - the Mappin & Webb Building - which features prominently in the Niels Lund 3. painting of 'The Heart of the Empire' (http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/mauri...). The developer, Peter Palumbo, was granted planning permission in 1968 to replace the Victorian buildings with a modernist office tower designed by Mies van der Rohe. But nothing materialised and, following opposition, the City withdrew planning permission in 1982. A planning inquiry in 1985 threw out van der Rohe's design but allowed the possibility of an alternative form of redevelopment. Stirling's design was also initially rejected by planners, and dismissed by Prince Charles as "an old 1930s wireless". At another public inquiry, the Environment Minister, Nicholas Ridley, ruled in favour of Stirling's plans, but there were further delays when conservationists appealed against Ridley's ruling. Why do you think this site provoked such fierce controversy? (For illustrations of what the Mappin & Webb Building looked like in its prime, see HRH The Prince of Wales (1989) A Vision of Britain, pp. 66-68).

Walking along Poultry, on its opposite (north) side, note the range of bank buildings erected in the inter-war years, including National Westminster Bank offices by Cooper (1929-32) [5] and the Midland Bank (now HSBC) Headquarters [6], designed by Lutyens (1924-39) .

Continue along Poultry and turn right down Old Jewry (the heart of London's medieval quarter). Explore some of the courts and alleys, and note the profusion of foreign banks. At the end of Old Jewry, turn right along Lothbury, cross at the traffic lights, and go past the back of the Bank of England. Visit the Bank of England Museum in Bartholomew Lane if you have time. Continue along Throgmorton Street and Old Broad Street, past the Stock Exchange Building (1972) [7] (opposite the Drapers' Hall [8]) and on past Tower 42 [9] (originally the Nat West Tower, designed by Richard Seifert, opened 1981, closed following IRA bomb damage in 1993, reopened 1995).

Cross over Wormwood Street/London Wall and go straight ahead. The Broadgate development [10] is at the end of the road (the entrance, to the left of the building at the end of Liverpool Street, is accessible although you may have to skirt hoardings that conceal Crossrail development works); Liverpool Street station [11] is to your right Go inside the Broadgate complex; walk past The Fulcrum, the 50ft iron sculpture by Richard Serra, and on to Broadgate Circle (and watch the ice-skaters if winter time). Continue to explore the complex if you wish. Is this public or private space? Is there a plaque? A 50% stake of the land belongs to British Land [the British Land Co]. The other 50% is now owned by 'GIC', described on British Land's website as "Singapore's sovereign wealth fund".

The old Broad Street Railway Station used to be on this side but was closed in 1986. Efforts are now being made to redevelop this site once again for a new HQ for UBS bank. Return to The Fulcrum and enter Liverpool Street Station [11] via the underpass called Octagon Arcade (past Body Shop, WH Smith, etc.). Carry straight on through the station, noting the redevelopment undertaken between 1985 and 1991, and exit via the escalators onto Bishopsgate.

Liverpool Street station was opened in 1874 (the original terminus of the Great Eastern Railway was farther north, on the other side of Bishopsgate). Part of the deal allowing the company to extend their line, knocking down slum housing, was the requirement to run trains at workmen's fares. Like many London termini, Liverpool Street has its own hotel - the Great Eastern Hotel [12] - opened in 1884, and also recently restored ( previously privately run by Sir Terence Conran and now owned by an American hotel operating corporation).

Leaving the station turn left along Bishopsgate and then right down Artillery Lane (so named because Henry VIII's Royal Artillery Company used to hold gunnery practice here). Notice how quickly the atmosphere changes as you leave Bishopsgate, crossing over into Tower Hamlets. Note the rehabilitated factories and houses occupied by a growing number of high end cafes.

Turn right down Sandys Row to see the Synagogue [13], the first separate Jewish synagogue to be built in the East End by Dutch Jews in 1874. The Dutch Jews worked as cigarette and cigar makers, diamond polishers and fruit and flower sellers in Spitalfields Market.

At Artillery Passage, on your left, no. 9a [14] is typical of houses built after the Great Fire. Farther along (at no. 15) lodged an Indian Assassin, Udham Singh, who came to London in 1937 to avenge the infamous massacre at Amritsar in the Punjab in 1919. Singh blamed Sir Michael O'Dwyer (Lieutenant-Governor of the region at the time of the massacre) and having tracked him down obtained employment as his chauffeur. Singh murdered O'Dwyer and was convicted and hanged at Pentonville Prison on 31 July 1940. In 1974 his remains were exhumed and flown back to New Delhi where he was honoured by the then Prime Minister, Indira Ghandhi. Note also no. 56 [14], built by successful silk merchants.

At the end of Artillery Passage, turn left and then immediately right on to Gun Street. Formerly at no. 40, although now replaced by flats, [15] the meeting of the Hebrew Socialist Union - the first separatist Jewish group - took place on 20 May 1876, under the leadership of Aron Lieberman, considered the prophet of Socialist Zionism.

Continue north up Gun Street, turning right at the end and walking towards Spitalfields Market [16], a fruit and vegetable market owned by the Corporation of London, closed in 1991. For the early history of campaigns to save the market, see Jacobs (1992). For more recent events, see http://www.spitalfields.co.uk/ and the other websites listed earlier.

Turn right and walk along Brushfield Street towards Commercial Street. At the corner of the market and across the road stands the pub called "The Ten Bells" [17], formerly known as the "Jack the Ripper" - you might reflect on why it changed its name.

Beside the pub the recently restored Christ Church [18], Spitalfields, which was built by Nicholas Hawksmoor, a contemporary of Christopher Wren, in 1729. The attached garden, popularly known as "Itchy Park" [19], was a traditional sleeping place for the poor and destitute homeless of London. There is a description of it in Jack London's The People of the Abyss (1903).

Turning right and walking south along Commercial Street be sure to look eastwards, to the left) onto Fashion Street. The name of the street belies its purpose - here is the beginning of the rag and leather trade. From the Huguenot silk weavers, to Jewish tailors, to Bengali garment factories, the rag trade has been one of the main sources of employment for the different groups of settlers who have made their homes in Spitalfields. The original Jewish garment industry is continued by Bengalis - although you will notice a mixture of land uses. This street was also where playwright, Arnold Wesker, grew up. One side of the street is dominated by the 'Moorish Market' [20], built by Abraham Davis in 1905, but closed (as a market) only four years later.

Continue south on Commercial Street all the way down to Toynbee Hall [21], a 'settlement house' (rather like a 'mission' but not so religious; a place where young Oxbridge graduates would go to live for a couple of years to help educate and 'improve' the East End poor) dating from the 1880s, is located three blocks further south at the junction of Wentworth and Commercial Streets.

Continue south all the way down to Whitechapel High Street. Turn left along Whitechapel High Street and if you have time go to Whitechapel Art Gallery [22] and explore the exhibitions and the arts bookshop (see http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/ for up-to-date information on exhibitions and events).

Then, if you continue along the main road (which changes its name to Whitechapel Road) you walk towards the East London Mosque [23], opened in 1985 (with a £1 million donation from the Saudi Arabian government).

Turn back and look for Osborn Street on the right hand side. Osborn Street soon becomes Brick Lane, the heart of the Bengali settlement in the area. Indian seamen have been living in the East End since the late 18th century. Amongst them from at least the late 19th century were Bengali-speakers from Sylhet (a rural district of what is now Bangladesh) and these were to provide the origins for the Bengali community that developed in the East End from the 1960s (see Adams 1987, Gardner 1992). In 1991 approx. 23% of the population of Tower Hamlets (39,955 people) were Bangladeshis; by 2001 this had increased to more than 33% (65,000). In Spitalfields and Banglatown ward, 58% of the population identified as Bangladeshi in 2001. While the traditional sources of employment have been the rag trade and the restaurant business (the founders of "Indian" restaurants in the UK are mainly Bengalis) these may not be the aspiration of many young British-born Bengalis (see Eade 1994).

Brick Lane has been the site of some of the worst racist attacks in London (sadly echoing the anti-Semitic attacks which took place during the 1930s). For example, in June 1978, 150-200 white youths rampaged through Brick Lane, resulting in deaths and damage to property. This coincided with elections in which British National Party candidates were standing. In 1993 a BNP candidate was elected in the Isle of Dogs, Tower Hamlets, although he was subsequently ousted. For more on Brick Lane, see you-well.co.uk

Head north on Brick Lane and then turn left along Fournier Street. On the corner stands a building which reflects the changing ethnic history of the area. It was originally built as a Huguenot chapel in 1742. In 1809 it was leased to the London Society for Promoting Christianity Among the Jews, but in 1819 it became a Methodist chapel. In 1897 it was bought by the Jewish ultra-Orthodox immigrant Machzikei Hadath society (mainly Polish and Russian Jews) and became the Spitalfields Great Synagogue. In 1976 the building became the London Jamme Masjid Mosque [24], or London Great Mosque. A minaret has recently been added to the building. It remains very much a spiritual centre for local Bengali Muslims - in contrast to the much larger, purpose-built East London Mosque [23] a few streets away on Whitechapel Road (Eade 1993).

In their adaptation of the building the local Muslims found themselves in dispute with the gentrifiers and city interests who moved into areas like Fournier Street during the 1980s as redevelopment took place and Bangladeshi garment factories were displaced and moved further south and east of Brick Lane. The Mosque Committee's attempts to adapt the building to accommodate more worshippers were strongly opposed by conservationists. For a long time, nothing was done to Islamise the building externally - except the list of prayer times on the noticeboard which was formerly used by the Talmud Torah School - although renovation took place inside to create more space. Note, however, that recent upgrading includes a new minaret, which was completed in December 2010. The 90ft Minaret is part of an £8.6m regeneration project which will also see new arches erected along Brick Lane (funded through a Section 106 agreement from the Bishops Square development near Liverpool Street Station.)

Fournier Street was the heart of Huguenot settlement in London. Many of its houses were built by Huguenot merchants in the 1720s - typical features are the narrow windows in the mansard roof. Consider the mix of residential and industrial uses along this street - and the evidence of gentrification. Almost all of the houses have been elaborately restored with wooden shutters, chandeliers and other 'period' features. Who are the current residents of such houses, and what effect are they likely to have on the neighbourhood?

Turn right down Wilkes Street, which also preserves many Huguenot houses, and then right again onto Princelet Street. Here again are some examples of renovated Huguenot houses. The first Yiddish theatre was once housed at No.3 Princelet Street [25]. What kinds of agencies and services are located here now?

No. 19 Princelet Street [26] combines a silk weaver's house from 1719 with a hidden synagogue, added in 1869 (the United Friends Synagogue, the first purpose built 'minor' synagogue in East London, and the third oldest surviving synagogue in England; it remained a synagogue until 1980). The building is planned to become a permanent Museum of Immigration and Diversity, but at the moment it is only open on a few days of the year (for details, see http://www.19princeletstreet.org.uk/).

Return to Brick Lane, stopping for an excellent (and cheap) curry if you have time. There are numerous options. For a full list of restaurants, see http://www.bricklanerestaurants.com

The route for the fieldtrip continues north along Brick Lane past the Truman Brewery [27a]. The brewery produced beer from 1666 to 1989, but is now a centre for small businesses, artists' studios, bars and night clubs. Continue under the railway bridge (where a Sunday market is held - notice the murals produced by local children) and past some surviving Jewish bagel bakeries.

[Diversion] One brief diversion: when you reach Bethnal Green Road, turn left to see the Rich Mix Centre [27b], opened in Spring 2006: a new creative space, funded by a mixture of public and private partnership, providing space for cultural activities including film, art and music which draw inspiration from the 'globalisation of people and culture'. For more information, see http://www.richmix.org.uk/

Cross Bethnal Green Road and continue up Brick Lane, turning left on Rhoda Street, right on Swanfield Street and left on Rochelle Street. This will lead you into Arnold Circus [28], the centre of the LCC's famous Boundary Street estate, erected in the 1890s on the site of a notorious slum ('The Nichol', fictionalised in Arthur Morrison's novel, A Child of the Jago). On Charles Booth's poverty map this area was dark blue and black. Note the architectural style of the blocks of flats, and some of the details of the design (the use of coloured brick, the roof details, the porches and entrances to different buildings). What condition is the estate in now?

Leave Arnold Circus by Club Row. Go over Bethnal Green Road by the pelican crossing and note the synagogue to your right (converted to industrial use) [29]. Go left, past Shoreditch High Street Station and under the railway through the tunnel (Braithwaite Street, formerly Wheeler Street) and turn right onto Quaker Street. Cross Commercial Street and go straight on down Elder Street. Note the conversion of industrial buildings to residential use. At the end of Elder Street, turn left (Folgate Street) and go on to the junction with Commercial Street. The Victorian building at the junction of Commercial Street/Folgate Street is the very first Peabody Buildings (1864) [30]. Are they still owned by Peabody? Who lives here now?

Turn right again and go back through the market to Liverpool Street Station.

Explore

Along this walk, within a few hundred yards, you pass from the financial and commercial centre of Britain into a low-income, ethnically mixed, inner-city area.

The walk deals with the following issues:

1. Contrasts between central and inner city;

2. Redevelopment, conservation and gentrification;

3. Ethnic and racial change

The tour exemplifies the impact of national and international changes on particular localities; it allows you to explore the changing social and economic geography of the city; and it encourages you to use your powers of observation to try to understand the urban environment. The walk concentrates on four main areas:

City of London: Much of the medieval City was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 but the various guild halls and livery companies (Pewterers', Brewers', Drapers', etc.) and street names (Ironmongers, Milk, Wood, etc.) all date from this period. The City then developed rapidly as a commercial and financial district of international standing: the 'Heart of Empire'. At the beginning of the 19th century around 130,000 people lived in the City of London. Its residential population declined to 27,000 by 1901 and to a low of 2,000 in the 1960s, prior to the redevelopment of the Barbican area, which had suffered heavily from bombing during World War II. Further new building and conversions of commercial property to residential during the 1990s meant that by 2001 the resident population of the City had grown to just over 7,000; between 1991 and 2001, the City's population grew by 34%, the highest growth rate of any local government area in England & Wales. Although, after the Isles of Scilly, the City still has the second smallest residential population of any English Local Authority - National Statistics 2009 mid-year estimates put the number of residents at 11,500 (up from 8700 In 2005).

In 2004 there were 354,000 daily workers in the City of London, including 124,000 in banking, insurance and related activities, and 106,000 in business services, especially legal, accountancy, recruitment and consultancy activities. Numbers fluctuate in line with booms and recessions. The number of jobs has fallen in recent years with the figures from 2009 suggesting there are 316,700 daily workers in the City. Canary Wharf however has continued to expand, with 80,000 jobs in 2006 and 105,000 jobs by 2009 (across all sectors).

The modern growth of the City depends largely on London's international financial status. Between 1970 and 1990 the number of foreign banks grew from 163 to 482, mainly based in western Europe, the USA and Japan. By 2003, these had consolidated at around 290. In international business lending, London is almost as big as Tokyo and New York combined. The City also has the largest foreign exchange market in the world and the third largest stock exchange, with more overseas companies quoted than anywhere else. 35-40% of office development in the City during the late 1980s boom was financed by foreign companies, primarily Japanese and Scandinavian. As well as new development, suitable for modern, computer-based business, many older buildings have been gutted and rebuilt behind their facades, largely to satisfy pressures to preserve the historic character of the City. By the mid-1990s, London as a whole had about 180 million square feet of first-class office space, compared with 300 million each in Manhattan and Tokyo. Rents are therefore high by international standards: about £60 per square foot for prime office space in 2000. The expansion of office space in the City, especially since the deregulation of financial services in 1986 (the 'Big Bang') increased development pressures on sites with the City and in neighbouring areas such as Spitalfields, as well as in the West End and at Canary Wharf. 2

There was a severe property decline in the early 1990s, followed by a strong recovery in the late 1990s. By 2005/6, demand was again strong but the recession of 2008 was accompanied by another downturn and it is currently unclear how the commercial property market is rebounding. Although in 2010 London was the largest commercial real estate market for investment activity globally, generating £10.8 billion of transactions, of which £7.3 billion was overseas money.

Spitalfields was a fruit and vegetable market owned by the Corporation of London. The market closed for redevelopment in 1991 and moved to Temple Mills in the Lea Valley. Parts of the market buildings were demolished to make way for 'City' type commercial and residential development. The remainder has been converted to a craft and organic foods market, appealing to a 'City' type population. But the surrounding area still includes a highly diverse population and a range of housing from near dereliction to carefully restored and gentrified properties. It has also provided a point of entry for a succession of minority groups over several generations. Some idea of the contrasting attitudes associated with different groups can be gained by comparing the upbeat websites of the Spitalfields Development Group http://www.spitalfields.co.uk/ , Visit Spitalfields http://www.oldspitalfieldsmarket.com/ and Ballymore (a property company that currently owns the remaining part of the market) surviving references in newspaper articles on the web to the anti-development 'Spitalfields Market Under Threat' (SMUT) which was active in defending the market from redevelopment in the early 2000s.

Brick Lane is the centre of the Bengali community in Tower Hamlets. They are the latest wave in a long history of immigration to the East End, preceded by Protestant Huguenots (refugees from France and the Low Countries at the end of the 17th century) and Irish Catholics and east European Jews (from the 19th century). Like these previous groups, the Bengalis have had to endure much hostility and harassment, with a high incidence of racist attacks in the area. While reinvestment has begun in several streets around Brick Lane, an earlier phase of redevelopment is evident just across Bethnal Green Road: Boundary Street.

The Boundary Street Estate was a pioneer example of large-scale public redevelopment, built by the LCC in 1898, replacing an area of notorious squalor with widened streets, blocks of 5-storey council flats, schools, courtyards, gardens and bandstand. It provided accommodation for 5-6,000 people. Under the 1987 Housing Act, the area was designated for rehabilitation by a Housing Action Trust, transferring control from the local authority into private hands. This was successfully opposed by local residents, but the price was a much slower, piecemeal renovation.

REFERENCES

The following sources can be supplemented by your own research in the London History Library (UCL), and the Guildhall Library in the City of London, and by visiting the Museum of London. The Tower Hamlets Local History Library is in Bancroft Road (near Queen Mary College). Also look at the Regency and Victorian A-Z atlases and the Charles Booth poverty map (http://booth.lse.ac.uk/). For further reading see the list below.

On the city of London:

Buck, N. et al. (2002) Working Capital, chapter 3.

Daniels, P.W. and Bobe, J.M. (1992) 'Office building in the City of London: a decade of change', Area 24, pp. 253-8.

Eade, J. (2000) Placing London: From Imperial Capital to Global City (Berghahn Books)

Hamnett, C. (2003) Unequal City, pp. 37-42, and chapter 9.

Pryke, M. (1991) 'An international city going "global": spatial change in the City of London', Environment and planning D: Society and Space 9, pp. 197-222.

Shaxson, N. (2011) Treasure Islands. See 'Griffin' Chapter

Wood, P. (2004) Discovering Cities: Central London (Geographical Association)

On number one, poultry:

Jacobs, J.M. (1990) 'Redevelopment in London' (UCL PhD, copy in Reading Room)

Jacobs, J.M. (1996) Edge of Empire, chapter 3

HRH Prince of Wales (1989) A Vision of Britain

On spitalfields:

Hall, T. (2005) Salaam Brick Lane: A Year in the New East End

Jacobs, J. (1992) 'Cultures of the past and urban transformation: the Spitalfields market redevelopment in East London' in Anderson, K. And Gale, F. (eds) Inventing Places

Jacobs, J. (1996) Edge of Empire, chapter 4

Phillips, D. (1987) 'The rhetoric of anti-racism in public housing allocation' in Jackson, P. (ed) Race and Racism

Taylor, W. (2001) This Bright Field: A Travel Book in One Place (Methuen)

On the social history of the east end:

Booth, W. (1890) In Darkest England

Bullman, J., Hegarty, N. and Hill, B. (2012) The Secret History of Our Streets

Fishman, W.J. (1988) East End 1888

Fishman, W.J. (1979) The Streets of East London

Glinert, E. (2005) East End Chronicles

Lichtenstein, R. (2007) On Brick Lane

Lichtenstein, R. and Sinclair, I. (2000) Rodinsky's Room

London, J. (1903, lots of modern edns) The People of the Abyss

Marriott, J. (2011) Beyond the Tower: A History of East London

Morrison, A. (1896, new edn. 1982) A Child of the Jago

Werner, A. (ed) (2008) Jack the Ripper and the East End

White, J. (1980) Rothschild Buildings: Life in an East End tenement block 1887-1920

Wise, S. (2008) The Blackest Streets: The Life and Death of a Victorian Slum

Yelling, J. (1986) Slums and Slum Clearance in Victorian London

On Bangladeshis in London:

Adams, C. (1987) Across Seven Seas and Thirteen Rivers: Life Stories of Pioneer Sylheti Settlers

Carey, S. And Shukur, A. (1985) 'A profile of the Bangladeshi community in east London', New Community 12, pp. 405-29

Eade, J. (1990) 'Nationalism and the quest for authenticity: the Bangladeshi in Tower Hamlets', New Community 16 (4)

Eade, J. (1989) The Politics of Community

Eade, J. (1993) 'The political articulation of community and the Islamisation of space in London' in Barot, R. (ed) Religion, Minorities and Social Change 8

Eade, J. (1994) 'Identity, nation and religion: educated young Bangladeshi Muslims in London's "East End"', International Sociology 9, pp. 377-94

Eade, J. (1997) Living the Global City

Gardner, K. (1992) 'International migration and the rural context in Sylhet', New Community 18, pp. 579-90

Glynn, S. (2002) 'Bengali Muslims: the new East End radicals?', Ethnic and Racial Studies (Nov. 2002), pp. 969-88

Glynn, S. (2005) 'East End immigrants and the battle for housing: a comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities', Journal of Historical Geography 31, pp. 528-45

Kershen, A.J. (2005) Strangers, Aliens and Asians: Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields (Routledge)

Contemporary fiction:

Ali, M. (2003) Brick Lane

Gavron, J. (2005) An Acre of Barren Ground

Kureishi, H. (1994) The Black Album

Close

Close