|

|

|

|

A Newly Discovered Neolithic Enclosure At Lower

Luggy, Berriew, Powys |

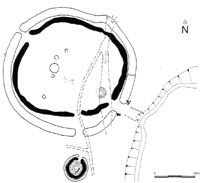

The enclosure was visible on the aerial photographs as a sub-rectangular cropmark measuring approximately 40m NW-SE by 30m SW-NE. The corners were rounded and there was an apparent entrance causeway close to the southern corner. A subsequent field visit detected no traces of either internal or external banks. The date of this enclosure was unresolved. While it fell into the general, if ill defined, class of ‘small enclosure’ and might therefore be considered to be of a later prehistoric date, nevertheless, it resembled a small enclosure at Brynderwen, 7.5km southwest of Lower Luggy, where a pit containing Fengate Ware was located within the enclosure area (Gibson and Musson 1990). Although the pit could not be related stratigraphically to the enclosure ditches, this find nevertheless offered tantalising possibilities for Neolithic settlement in the valley of the Upper Severn. The proximity of the Lower Luggy enclosure to the long barrow further enhanced this possibility. Accordingly, a small excavation was planned to try and date the enclosure.

The excavation trench was located over the entrance causeway of the enclosure and the western ditch terminal. Some large postholes within the entrance may hint at some form of gate, although the exact nature of this feature remains unresolved. The ditch silts were derived from the inside of the enclosure, presumably from an internal bank. Finds were few and derived entirely from the ditch or the overlying ploughsoil. They comprised small flint flakes from the secondary silts in the ditch. A charcoal deposit was located directly on the floor of the ditch terminal beneath the primary silts. This has yet to be identified but appears to be primarily oak. However, small twig charcoal was identified, with no more that 3 annual growth rings, and one of these twigs was submitted to Beta Analytical for AMS dating. A date of 4720±50 BP (Beta 177037) was obtained from this twig. This calibrates to 3640-3370 Cal BC (at 2s). This is exactly contemporary with the dates for the Lower Luggy long barrow (c.3700-3300 BC- BM 2954 & 2955) and is slightly earlier than the 2 dates from the Fengate pottery recovered from the Brynderwen enclosure mentioned above (c.3350-3000 Cal BC-OxA – 4409 & 5317). This places the enclosure firmly in the earlier part of the middle Neolithic. Problems persist. As mentioned above, the Brynderwen enclosure cannot be stratigraphically tied to the Fengate-producing pit within it and secondly, the full outline of this enclosure has not been determined as it is pertly overlain by a railway embankment. Thirdly, even when from a sealed context and from a young sample, the over reliance on single radiocarbon dates is dangerous, especially given the lack of cultural material from the Lower Luggy excavation. Nevertheless, there are similar corner-entranced sub-rectangular enclosures within the Upper Severn Valley and the two that have been partially investigated have produced Neolithic material. This may suggest that we have a ‘new’ type of middle Neolithic enclosure in this area or, at the very least, not all small enclosures need be of later prehistoric date. Further work at the enclosure is planned. The excavation was generously financed by the National Museum and Galleries of Wales and the University of Bradford and was run as a student training excavation. I am grateful to the landowner, Mr Bob Jones of Trehelig, for permission to excavate and to the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust for the loan of some equipment and for SMR advice. Alex Gibson References

|

It is a very great pleasure to have been asked to take over the reins of PAST. There can be no excuses now for failing to keep up with the latest news! Being based in Dublin, I suspect that there may be more than the occasional article of Irish interest in the pages of forthcoming issues, and details of one exciting new discovery are included here. By way of introduction to my own research interests, I have also included a short report on fieldwork I am involved in on Shovel Down, Dartmoor. Tempting as it was to devote the entire issue of PAST to the shovel Down Project, I was sufficiently restrained not to test the patience of readers in such a way! Instead, I hope that you will find in these pages the usual informative mixture of articles covering the Palaeolithic to the Iron Age, Britain to South America, including reports on conferences, study tours, excavations, new research projects and other events. As ever, please do continue to send in news and views- articles on the latest research and excavation, and your ideas on current issues and developments are all very welcome. Don’t forget that old issues of PAST are now posted on the Society’s website, so if you submit an article, you might like to include relevant web links. Joanna Brück

|

| The public enquiry into the Stonehenge road scheme will open on 17 February 2004. The short bore tunnel, 2.1km long, proposed by the Highways Agency and supported by English Heritage, is considered by many archaeologists to be too short. The Prehistoric Society joins the Council for British Archaeology, the International Council on Monuments and Sites UK, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, the Campaign to Protect Rural England, the National Trust and Rescue in objecting to the scheme. Our recommendation is that the tunnel should be a 4km long-bore operation. The west entrance needs to be clear of the Winterbourne Stoke barrow cemetery. The east entrance should be not only at a greater distance from King Barrow Ridge, but should also permit the line of the Stonehenge Avenue to be reconnected once more. The public inquiry will establish whether the scheme is to take account of the entire World Heritage Site or merely the single monument of Stonehenge at its centre. Mike Parker Pearson

|

| CONFERENCE

NEWS |

||

| The 51st Congress of Americanistas in Santiago,

Chile, July 2003. The 51st Congress of Americanistas in Santiago de Chile, July 2003, was attended by over 3500 delegates from around the world and covered diverse subjects from literature to politics, including archaeology. Session ARQ-9 concentrated on the archaeology of hunter-gatherer societies and was organised by Fernando Oliva from the University of La Plata together with Caroline Wickham-Jones from Scotland, in order to put colleagues from both sides of the Atlantic in touch with one another and to generate discussion on various approaches and interpretations in the field. Despite various economic difficulties, the session was well attended by speakers from several European countries as well as from the different countries of South America, and we were joined by many colleagues, including some from North America, who came to listen and participate in the discussion. The papers presented a wide range of approaches and information and the result was very stimulating. Themes varied from the mobility patterns of recent hunter-gatherers in northern Argentina, through experimental archaeology in Tierra del Fuego, to geophysical work in Soctland and the patterning of lithic resource procurement in France. One strong theme that emerged, of particular interest to this author, is the development of fisher-gatherer-hunter societies in coastal regions at high latitudes. These areas offer particular conditions: fjord-like coastlines that provide abundant resources and relatively safe access. Hein Bjerck from Trondheim has done much to promote contacts and study in this field and it is of great relevance to Scotland as well as to the more extreme areas. Papers in this and related sessions looked at areas such as Tierra del Fuego, northwest North America, the Arctic, Norway and Scotland. Other papers looked at more recent times. An interesting contribution by Marcela Mendoza of the University of Memphis considered the movement of Toba bands in northwest Argentina in the early 20th century. This study was based on oral history and was able to provide a view of the choices relating to movement and other things. A few papers highlighted the contribution of artefact studies such as lithic raw materials to an examination of territory and movement. There was an interesting comparison to be made between studies by Fernando Oliva in the Pampa region of Argentina and studies by Estelle Yven in Brittany, France. It is all too easy for academic archaeologists to look to their nearest neighbours for inspiration. Contacts across Europe and between Europe and North America are well established. There is, however a great deal of interesting work going on in South America, and much of it is of great relevance to those of us who study in northern Europe. One barrier lies in the language: for those of us from northern parts, Spanish is not a common second language so that the literature often remains unavailable. Likewise, though for other reasons, many South American archaeologists have little access to European publications. The great value of a conference like this is that it can widen the academic net beyond the normal – to include even areas that might not at first be regarded as of likely interest. This is of great benefit to both individuals and the profession as a whole. Another important factor that has served to reduce the academic distances is recent years lies of course in the internet. Publication of the ARQ-9 session is planned to take advantage of this. The papers will appear in the e-journal Before Farming (www.waspress.co.uk), which also publishes a paper volume at the end of every year so that you will have something to sit on your shelf (or read in the bath). Electronic publication has been chosen in order to maximise worldwide access to the papers and with this in mind some funds have been raised to help with translation. In this way it is hoped to publish bi-lingual papers. Great thanks must go to the conference organisers for a magnificent job. Projectors worked, laptops were provided and room heaters found. Round-the-clock internet access was appreciated by many. Few will forget (though some might prefer to) the receptions with free flowing pisco sour, and there was a fantastic programme of related cultural events and tours. It was this writer’s first experience of the Congress of Americanistas but I would recommend it as a conference worth attending should you get the chance: rumour has it that the next meeting in three years time is to be held in Europe. Thanks are due to my fellow co-organiser, Fernando Oliva, and to all those who gave papers or attended the session. Finally, I should like to acknowledge the generous and imaginative support of the Prehistoric Society, which together with support from the British Academy, the Quaternary Research Association, the Council for British Archaeology and the Russell Trust has enabled the author to co-organise, participate in and publish the session. C.R. Wickham-Jones, Orkney

Meso 2005: The 7th International Conference on The Mesolithic

in Europe Belfast Every five years specialists from around the world working in the field of Mesolithic studies come together for an international conference. Previous venues for this major academic conference include Warsaw, Potsdam, Edinburgh, Leuven, Grenoble and Stockholm. At the last meeting at Stockholm in 2000, Ireland was voted for by participants to be the next venue for the 2005 conference winning this privilege over Russia and Portugal. Belfast has been chosen as the host city and the Queen’s University of Belfast’s excellent lecturing facilities should ensure the conference’s success. Fieldtrips are planned for before and after the conference. The pre-conference trip will take visitors to Mesolithic sites in the Irish midlands and on the east coast around Counties Dublin and Louth. The post-conference trip will focus on the Bann valley, the north Counties Antrim and Derry coasts and parts of County Donegal. During the course of the conference two half-day trips are also planned to Strangford Lough, County Down, and to Mesolithic raised beach sites on the east Antrim coast such as Cushendun and Larne. Between 150 and 200 participants are expected from some 25 countries. Previously, in addition to most west European countries, delegates have also come from North America, Canada, Russia and several eastern European countries. Very often it is only during these conferences that many of these people meet. The conference will explore many of the issues pertinent

to the study of prehistoric hunter-gatherer- fishers such as the environment,

colonisation processes, raw material procurement strategies, mobility,

territoriality, artefact analysis, settlement, social structure, and

symbolic and ritual behaviour. There will be over 100 lectures as well

as an opportunity to present poster displays. The lectures will also

form the basis for the publication of the conference proceedings. Collectively,

the lectures and displays, and finally the publication, will inform

the audience of the many developments, new discoveries and interpretations

of the evidence for the Mesolithic period in Europe. Finally, in December 2002 the conference organisers

launched the web site for Meso 2005. Anyone who is interested in finding

out more about the conference and would like to be kept updated with

information log on at:

|

| THE

STONEHENGE RIVERSIDE PROJECT: NEW APPROACHES TO DURRINGTON WALLS |

|||

Stonehenge may not usually be thought of as a ’riverside’ site, but its link to the River Avon via the Avenue, together with the presence upstream of the monument complex of Woodhenge and Durrington Walls, highlights a stretch of river which could have had significance as a funerary and processional route in the Later Neolithic. Our work in 2003 has focused on the upstream end of this riverside at Durrington Walls – Britain’s largest known henge enclosure – where Geoffrey Wainwright excavated spectacular wooden post circles in 1967 in advance of the re-routing of the A345. One of the entrances of Durrington Walls faces southeast towards the river and we wanted to find out whether it too had an ‘avenue’ linking the monument to the river. In 1996, English Heritage carried out a magnetometry survey on the western half of Durrington Walls, revealing five enigmatic ditched enclosures within its interior as well as a series of anomalies at its centre and traces of Iron Age field systems and pit complexes (David & Payne 1997, 91-4). In 2003, English Heritage surveyed the eastern half and the area between the southeast entrance and the river. Although the colluvium is over a metre deep in this zone, there were some intriguing results. A linear anomaly leads from the riverside towards the northern terminal of the entrance which is flanked on either side by two clusters of anomalies. Within the henge’s eastern circuit there were further interesting results: evidence of ’gang-digging’ of the ditch in sections about 40m long, and a curvilinear ditch beneath the bank on the east side. This looked at first to be a pre-henge enclosure ditch but, when viewed together with aerial photographs, it appears to be a terminal for the bank, indicating either a much wider original entrance or the starting point for the henge bank’s construction. Southwest of the entrance, Wainwright’s hunch that the irregular kink in the ditch might be the result of bad planning by Neolithic diggers (Wainwright R Longworth 1971, 19) is supported by signs of a possible re-cutting of the ditch on a different alignment.

The magnetometer survey was followed up in September 2003 with a contour survey over the eastern half and a programme of coring outside the southeast entrance. The geophysical anomalies on either side of the entrance were identified as the result of burnt deposits which post-date the bank. There is also a buried soil which survives not only beneath the bank but also across the entrance and immediately in front of it. Closer to the river, the ground drops within a steep-sided ’cutting’ over 2m deep and about 40m wide whose northern edge corresponds with the linear anomaly. At the riverside, this cutting is visible as a substantial earthwork feature. Durrington Walls is sited within a hanging valley and the cutting undoubtedly has a geomorphological origin as a valley bottom terminating in a low river cliff. However, its sides and base may well have been artificially enhanced in prehistory and further coring and excavation will clarify this. The beginning of this project has provided an opportunity to reassess Durrington Walls and its relationship with Woodhenge. Unlike Avebury, this enormous 17-hectare enclosure appears incongruously positioned, on the steep slope of a small valley. Yet, it was no doubt carefully sited, with its northwest and southeast entrances emphasising a downhill line of access from the high ground of Larkhill to the riverside. Climbing to the flat summit of Larkhill, there are views – or there would be without the military buildings and modern tree cover – of every Neolithic monument in the Stonehenge area as well as of Salisbury Plain’s terrain on both sides of the Avon, a zone which has the largest and densest concentration of Early Bronze Age round barrows in Britain. Colin Shell and Gill Swanton had also noticed Larkhill’s vistas earlier in the year, and the significance of this hilltop is enhanced by its alignment with the Avenue as it leads into Stonehenge on its solstice axis. The Larkhill ’panopticon’ is perhaps a rather grand a name for this viewpoint but it does emphasise its suitability for surveillance of the landscape. Who knows what might lie beneath the hill’s surface? Woodhenge’s relationship with Durrington Walls has always puzzled archaeologists: why are the two adjacent and are they of the same date? The magnetometry survey highlights the misalignment of Durrington Walls’ ditches on the south side of the monument either side of the old A345, a misalignment so striking that it seems unlikely that the ditches can join up. The surface contours and an early aerial photograph strongly suggest the existence of a third entrance here. Unfortunately, magnetometry has yet to be carried out along the southern perimeter of the monument but it should resolve this enigma. We can speculate that this entrance led directly to Woodhenge along a short avenue. This north-south axis through the henge enclosure may also have been marked by the construction of a north entrance, subsequently blocked during the Neolithic period. The ditch appears to constrict where the two modern roads pass through the north perimeter whilst the bank departs from its symmetrical oval plan with a small kink which was found in 1967 to post-date an earlier line of posts. Were this once a fourth entrance, then Durrington Walls began life as a monument much more like Avebury and Mount Pleasant in plan than hitherto realised. But why was this entrance blocked off so early in the monument’s use?

Ever since the 1966-1968 excavations, archaeologists have speculated as to whether or not Durrington Walls’ timber circles were roofed. In our view, the balance of evidence favours a centuries- long continuous tradition of erecting free-standing posts which were deliberately left to rot – perhaps a collective of ’totem poles’, as Mike Pitts (2001) has suggested, to memorialise dead individuals. We wonder whether the artefact-rich weathering cones formed within the tops of the decayed post pipes were actually pits, each recutting its near-filled posthole so that offerings could be made (cf. Richards R Thomas 1984). Were such pits dug by the descendants of long-dead ancestors whose physical presence, formerly marked in wood, had become obliterated by the ravages of time? Our first season of work has produced few concrete results and many unanswered questions. We do not know for certain whether there was a ceremonial avenue linking the henge enclosure to the river. Nor can we yet be absolutely sure about the third and putative fourth entrance to the monument. Equally, the link to the Larkhill ’panopticon’ – and the significance of that hill as a viewpoint – may be purely fortuitous. Yet, these uncertainties ought to be resolvable though co-ordinated survey and excavation. Within the wider view, we also hope to clarify the extent to which the Later Neolithic symbolic and processional axis – from Larkhill through Durrington Walls and southwards along the river to the Avenue and Stonehenge – represents a major re-ordering of an Earlier Neolithic east-west axis along the cursus (Parker Pearson 2000). At an even greater scale, the project is part of an international investigation ’Millennium to millennium: living in cultural diversity 3000-2000 BC’ involving the Universities of Kalmar, Manchester, Sheffield and Stockholm, and the project’s research design is already in press (Parker Pearson R Richards with Payne in press). Mike Parker Pearson, University of Sheffield;

Acknowledgements References

|

|

The Craven Museum’s lithics collections are now available in virtual form as a fully interactive, illustrated database. The database contains information on a total of 51,330 artefacts donated to the Craven Museum by more than fifty individual collectors over the past 70 years, and includes important material from local archaeologists John Crowther, Lionel Atkinson, Arthur Waters, Welbury Holgate and Arthur Raistrick. Although most of the items come from the Craven

area of North Yorkshire, 574 sites from other geographical regions

are also included. Well- documented sites within the Craven area are

shown on a series of 58 township maps; these are further enhanced

with 3,788 pairs of illustrations showing a total of 15,383 worked

objects. The CD-ROM set can be obtained from Craven Museum, Town Hall, High Street, Skipton, North Yorkshire, BD23 1AH. The cost is £20.00 per set plus p+p. Cheques should be made payable to Craven District Council.

|

|

| Two members (one in Sussex and one in Dorset) need

to free up some shelf space and are offering runs of PPS (one 1983-2000

inclusive; the second 1989-2002 inclusive), free to a good home providing

the ‘buyer’ collects or arranges delivery at their expense.

They would prefer the sets to go to student members. If you are interested

in the Sussex run, please contact Julie Gardiner (Wessex Archaeology,

Portway House, Old Sarum Park, Salisbury SP4 6EB; tel. 01722 343413;

email: j.gardiner@wessexarch.co.uk).

For enquiries regarding the Dorset run, contact Tessa Machling (Institute

of Archaeology, 31-34 Gordon Square, London WC1H OPY).

|

|

| This year’s Europa Lecture will be held on Wednesday 19th May, not Wednesday 26th May as previously advertised. Time and venue as before.

|

|

| THE

PREHISTORIC SOCIETY’S VISIT TO NORTHUMBERLAND NATIONAL PARK |

|

|

Participants on this year’s UK study tour were based in the small town of Wooler, lying on the northeastern edge of the Northumberland National Park (NNP). On the first evening, we were welcomed by Peter Forester, deputy chair of NNPA. He and the archaeologists employed by the park made it very clear at the outset that they had a considerable and significant landscape to show off. The bulk of each day was spent exploring the landscape on foot accompanied by Rob Young of NNPA. Al Oswald of English Heritage, responsible for a project surveying the hillforts in the area, also accompanied the group throughout. On the first day, the group was led by Iain Hedley of NNPA. We visited College Valley, which, like other valleys in the Park, provided a focus for ancient settlement. It quickly became evident that there had been dense occupation of the area during some phases. Apart from the hillforts, generally thought to date to the Iron Age, for example East Laddies Knowe and Ringchesters, the landscape was dotted with cairns and groups of ’Romano- British’ round houses. There was also widespread evidence of arable farming in the form of ‘rig’ (comparable to the ‘ridge and furrow’ fossilised landscape elsewhere in England) and significant areas of ancient terracing. During the second day, the party was joined by Philip Deakin and Stan Beckensall, the latter generally acknowledged as an authority on rock art in Britain and particularly in Northumberland. Naturally, the focus of that day was the many examples of rock art around Lordenshaws above Rothbury and the River Coquet valley. The wealth of landscape evidence in this relatively small area included burial cairns, enigmatic tri-radial cairns of debatable date, a hillfort and other settlement evidence, all of which were easily accessed. The only disappointment was that poor weather truncated a planned climb on to Simonside.

The following day was led by Paul Frodsham, team leader for NNPA archaeology, and concentrated on the Breamish Valley which showed further evidence of multi-period occupation. Sites at Brough Law, Turfe Knowe, Ingram Hill and Wether Hill were visited, and the day finished with a visit to the excavation at Ingram South, a joint NNPA/Durham University project. On the final day, the chronology of the sites stretched from the Mesolithic, with the reconstructed house at Maelmin, to the site of Yeavering ’Old Palace’ dating to the 7th century. In between, the last long climb took in Humbleton Hill hillfort with the bonus of spectacular views on a very clear day. While the trekking across the very handsome hills and valleys, the local archaeologists presented their views but freely admitted that the paucity of excavation in the Park has frustrated their attempts to synthesise a coherent chronology for the landscape. On several occasions, they argued strongly for a change in the current conventional wisdom of putting conservation ahead of excavation. They feel that a limited programme of sample excavations could give them great insight into this fascinating terrain. Certainly, there was a good deal of lively debate, aided and abetted by the presence in the party of the three professors: John Coles, Peter Fowler and the Society’s President, Graeme Barker. Follow-up lectures each evening provided excellent background to the sites visited. Debate tended to be brief as the combined effects of long days in the fresh air, good food and the odd glass of wine took over. In summary, the tour was a revealing, stimulating and enjoyable insight into a landscape that is arguably much under-rated in terms of what it has to tell us about ancient occupation. Steve Taylor, Winchester

|

|

| The Third Sara Champion Memorial Lecture was delivered by Rachel Pope (University of Wales, Bangor) on 15th October. Rachel gave a thoroughly stimulating and entertaining talk on ‘Social change in Later Prehistory: Evidence from the Northern Roundhouse’, in which she traced shifts in architectural form and settlement location, and linked these to factors such as changing climatic conditions and the development of new economic practices. Our former President, Tim Champion, was present, and the lecture was followed by a reception at which both wine and discussion flowed!

|

|

| Historic Scotland first produced a formal policy statement on carved stones in 1992. Guidance is being prepared that is intended to supersede, update, expand and clarify recommended practice in the face of recent research and best conservation practice. This relates to prehistoric rock art, Roman, medieval and post-Reformation sculpture, in situ and ex situ architectural sculpture and gravestones. The draft guidance will be circulated for public consultation early in 2004. If you would like to be notified of this so that you may have the opportunity to comment, please send your contact details (preferably an e-mail address) to trish.stewart@scotland.gsi.gov.uk or Trish Stewart, Historic Scotland, Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh, EH9 1SH. Dr Sally Foster, Senior Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Historic Scotland, E3, Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh, EH9 1SH Tel. 0131 668 8658, email: sally.foster@scotland.gov.uk

|

|

|

EXCAVATIONS OF BRONZE AGE FIELD

SYSTEMS ON SHOVEL DOWN, DARTMOOR, 2003 |

||

| The division of the landscape into fields is a recurring element of the early agricultural history of north-west Europe. In most regions, this occurred many centuries after the adoption of farming, and it appears to indicate fundamental transformations in the nature of social and economic life. The Bronze Age boundaries on Dartmoor, south-west England, are among the best known examples of this process. Dartmoor’s fields take a variety of different forms, but among the most striking are the systems of coaxial boundaries. These consist of large blocks of fields that follow a common alignment. The coaxial boundaries on Dartmoor, known locally as ’reaves’, are particularly impressive both due to their scale – field systems may enclose several thousand hectares – and because they still survive as substantial stone and earth banks in the modern landscape. The detailed archaeological study of the reaves was pioneered by Andrew Fleming during the 1970s and 80s, and his work remains extremely influential (e.g. Fleming 1988). Prominent amongst his ideas was the argument that the field systems represent the imposition of a planned layout co-ordinated by a central authority over a relatively short time. There has been little by way of either fieldwork or re-analysis to challenge these ideas, though recently it has been suggested that the process of construction was not planned but emerged gradually from earlier land use practices (Johnston 2001).

The Shovel Down Project set out in 2003 to examine the process of land enclosure on north-east Dartmoor during later prehistory. The programme of research involved survey and excavation of a large field system, as well as extensive palaeoenvironmental investigation. The primary aims of the project were to examine the junctions of major elements of the field system for evidence of chronological depth and accretionary growth, to reconstruct the environmental history of the study area, and to assess the effectiveness of methodologies that had so far seen relatively little use on Dartmoor such as OSL dating and geophysical survey. The fieldwork was funded by the British Academy, the Dartmoor National Park Authority, University College London, and University College Dublin. The excavations were carried out by a hard-working and enthusiastic team of students and local volunteers. Specialist input was provided by Dr Ralph Fyfe, University of Exeter; Dr Helen Lewis, University of Oxford; Dr John Meadows and Dr Kris Lockyear, University College London; Louise Barker, English Heritage; and Dr Philip Toms, University of Gloucestershire. The three main excavation trenches (A, B and D) were located at major junctions along what was thought to be a ‘primary’ (or ‘axial’) element of the field system. Previous ground surveys suggest that this reave was built as a single structural unit and that it was used as a base-line for the series of north- south boundaries which divide the area into large blocks. A further trench (C) was situated in a small valley mire where the axial boundary was overlain by up to 1m of peat. Four small slots were also made where a medieval water channel (or ‘leat’) truncated the boundaries. In Trench A, the junction had been disturbed by later peat cutting and stone robbing. Only two stone-lined hollows on the alignment of one of the reaves hint at the earlier presence of a boundary. Nevertheless, the trench proved interesting in other ways. Most significant of all was the recovery of evidence for activities predating the construction of the boundaries, and that may be contemporary with a complex of stone rows and cairns nearby. These included a small oval pit and a stone feature comprising an incomplete arc of large granite blocks. A total of 74 worked flints were recovered from the trench. Trench B was located at the intersection between the Shovel Down axial and the ‘terminal’ reave or upper boundary of a series of long coaxial strips. Here, the boundaries were well-preserved, comprising drystone walls which survived in places to four courses high. Interestingly, the excavated evidence indicates a rather different construction sequence than was initially expected. The earliest surviving phase was a right-angled corner where the terminal reave and the western section of the axial boundary were ’keyed in’ to one another to form a continuous wall. This corner was later abutted by another length of wall which continued the line of the axial reave to the east. This demonstrates that the axial boundary was not built as a single structure, but emerged through the conjoining of different elements. There was evidence for the rebuilding of parts of these boundaries and a section of the terminal reave appeared to have been pulled down and reconstructed in a different style. A 1.9m wide gap, roughly surfaced with cobbles, formed an access way through the axial reave east of the junction. This entrance was cut through the boundary some time after its construction when the wall had already begun to collapse. A worked flint flake was found on the cobbled surface, suggesting that it was laid in prehistory. The reworking of the boundaries, involving episodes of rebuilding and the creation of new access routes, demonstrates that the boundary system was adapted and changed during its history.

The westernmost trench (D) was located at a junction between the axial boundary and a large block of land to the south. The walls in this trench had been disturbed by later episodes of stone-robbing, so that it was not easy to define the construction sequence. There are two possibilities. The loose stone that overlay the undisturbed portions of the boundary appeared to show a continuation between the southern and western sections of the junction. This was then abutted by the eastern boundary. Contrary to this, the in situ facing slabs on the south-eastern side of the junction, linking the eastern and southern elements, appeared to be of one build. The western element, it could be argued, abutted this corner. In either case, the evidence again indicates that the Shovel Down axial is not a single structural unit, but is made of up several conjoined lengths of boundary built at different times. The boundary excavated in the mire (trench C) was found to be sandwiched between two layers of peat. Monolith and bulk samples were collected from hoth above and below the wall for radiocarbon dating and to facilitate studies of plant macrofossils, pollen, waterlogged wood and insect remains. These will provide valuable evidence for pre-reave land-use as well as environmental changes associated with the construction, use and abandonment of the field system. Off-site environmental sampling was carried out both in this mire and in a second mire to the west. Auger surveys were undertaken to examine the stratigraphy of the sediments and to recover samples for pollen analysis. The slot trenches located at the intersection between the prehistoric boundaries and the medieval leat allowed vertical sections of the field walls to be exposed and demonstrated that the reaves varied cons’iderably in construction style even along the length of a single boundary. Pre-boundary features were recorded within Leat Trench 1 including a possible ditch running along the same alignment as the later wall, as well as a ‘hollow way’, running parallel and just to the south of ditch. The results obtained thus far suggest that rather than being imposed on the landscape ‘wholesale’, the boundaries on Shovel Down have a complex and potentially lengthy history. Episodes of rebuilding indicate the maintenance of the boundaries over time, while alterations such as the construction of the cobbled entranceway in Trench B may indicate changes in patterns of land-use. The possible ditch and ‘hollow way’ in Leat Trench 1 hint that the later field system was not ’imposed’ on the landscape but may instead have built on a long history of pre-reave land-use practices. Interesting evidence for pre-reave activities was also recovered in the form of lithics and other features in trench A. Further investigation of the extent and character of these finds may cast light on the historical context in which the field system was constructed. Perhaps most significantly, the axial reave does not appear to have been built as a continuous feature but comprised a series of separate sections. The construction of the field system may therefore perhaps be characterised as an incremental process, rather than a large-scale building project. Of course, if the stone walls overlay earlier boundaries of which no trace remains, then it may only have been the reaves themselves that were built ‘piecemeal’; the original boundaries may still have been laid out as an integrated system. Alternatively, it is possible that the stone boundaries were built and rebuilt during the occupation of the fields; in this way, a wall that was originally one long boundary would acquire a patchwork appearance comprising different sections and styles of walling. Whatever the case, the construction and use of the field systems on Dartmoor must be seen as a dynamic and ongoing process. Hopefully, the results of forthcoming dating and scientific analyses will help elucidate these questions. A summary report of the fieldwork will soon be available online: www.bangor.ac.uk/history/research/shoveldown/ Joanna Bruck, University College Dublin; References

|

||

| |

The Prehistoric Society Home Page |