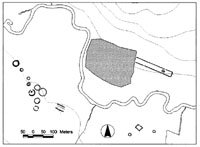

Figure 1. Southwest Libya, showing

the main focus of the Society's Libya tour, from Germa (top right)

to the Tadrart Acacus mountains (bottom left), then east across

the Erg Uan Kasa sand sea and along the southern edge of the Messak

Settafet to Wadi Mathendusch, and back to Germa. |

The Society's

2002 Study Tour was to Libya, specifically to see the rich archaeology

of the province of Fezzan in the southwest, deep in the Sahara (Figure

1). When I first proposed the Libya trip to Council a few years ago

I had no idea I would be the Society's President when it finally came

to fruition, but I always hoped to be part of such a tour. Although

I have worked extensively in Libya, I have never been to the far southwest

to see the wonderful rock art there, the rock paintings of the Tadrart

Acacus mountains and the rock engravings of the Messak Settafet plateau,

which were to be the highlights of the tour. The other reason I proposed

the tour was that my Leicester colleague David Mattingly was running

a large multi-period survey and excavation project (the Fezzan Project:

Mattingly, 2000), so it seemed an ideal opportunity to use his expertise!

David and I were the lecturers on the trip, with Dr Isobel Sjöström

(an experienced Saharan archaeologist who has worked on a number of

Libyan and Sudanese field projects) the Andante Representative. The

student place was awarded to Michael Rainsbury, who has just completed

a Masters in Prehistoric Rock Art at Durham (and who has strict orders

to write something for PAST in due course!). We gathered at Heathrow

in the wee small hours of Monday 14 October, and by the afternoon, via

Amsterdam, we were all in the Libyan capital Tripoli. We were very ably

looked after in Libya by Abdul Heba, the Representative of Winzrik Tourism

Services, the local travel company who were working with Andante on

the tour arrangements. We walked round Tripoli's Medina (Old City) in

the falling light, and everybody was taking sweet minted Libyan tea

in the shadow of the Old Castle (Tripoli's finest historic monument,

now housing the National Museum and the Department of Antiquities) as

the muezzin called out through the dusk - we had thoroughly arrived.

Figure 2. The summit of the

Takhakhouri Pass in the Tadrart Acacus. |

The overarching

theme of the study tour was the transition from foraging to farming

in the Sahara, with the tour arranged in chronological reverse order.

On the morning of the second day we flew south to Sebha, the capital

town of Fezzan, where our party was divided between five battered Toyota

Landcruisers, and we spent the rest of the day working our way southwest

down the Wadi el Ajal oasis visiting Garamantian sites investigated

by David's project. The Garamantes were a remarkably complex state-organised

society that controlled Fezzan in classical times, trading variously

with the Punic and Roman world to the north, the Egyptians to the east,

and the Sahel peoples on the southern side of the Sahara. David showed

us round his major excavations of the ancient city of Germa, the Garamantian

capital, where he has exposed a continuous stratigraphic sequence from

c.500 BC to the present day. We also looked at Garamantian tombs (there

are estimated to be over 100,000 down the wadi), and foggaras, the underground

water channels once thought to be Islamic in date but which his project

has shown convincingly were in fact a Garamantian technology, the basis

of the intensive oasis farming that sustained their state. In the falling

light we scrambled over the hilltop fortress of Zinchecra a few kilometres

from Germa, where excavations by Charles Daniels in the 1960s revealed

evidence for complex protohistoric sedentary societies, the beginnings

of the Garamantian state system, c.1000-500 BC. That evening we slept

in a hostel belonging to Winzrik, where we also picked up our camping

gear and the kitchen truck that was to accompany us on the desert trip.

The final member of the party was a charming member of the Libyan security

services (one accompanies every tourist group), who had never been into

Fezzan before and turned out to be the keenest tourist of all of us.

Figure 3. Uan Afuda cave.

Figure 3. Uan Afuda cave. |

On the morning

of the third day we travelled into the Ubari sand sea on the northern

side of the Wadi el Ajal oasis to visit some extraordinary relict lakes

there which the Fezzan Project has shown were foci of settlement for

Mesolithic foragers and Neolithic forager-herders. This visit also introduced

the party to the way you have to drive across sand dunes: charge full

tilt (slipping back down if you don't make the top) but crucially manage

to stop on the crest, so you can see whether you can get down the other

side without taking off if the slope on the far side turns out to be

vertical. We managed to visit some spectacular mudbrick Garamantian

pyramid tombs under restoration by the Department of Antiquities, before

setting off on the long road journey southwest towards the desert settlement

of El Uwaynat near the Algerian border at the top of the Tadrart Acacus

mountains, where we were meant to be heading off road. However, we had

some long delays from bad punctures to the kitchen truck, and we eventually

made our first camp in the dark in a bowl in the sand dunes (our drivers

always chose these, to be out of the wind). With some trepidation I

watched some well-known Society members reading by the light of the

car headlights their instructions about how to assemble the new tents

they had been given. There were anguished cries of 'I haven't done this

for 20/30/40/50/60 years! [tick number of years as appropriate!]

Figure 4. Society members examining

rock art in the Wadi Teshuinat (Tadrart Acacus). |

We almost had

a major logistic crisis the next day, because there turned out to be

no petrol in El Uwaynat and our desert journey needed all the vehicle

tanks full as well as the dozen or so jerry cans we also carried. Abdul

and the security agent even tried the local army garrison, but got a

dusty answer. The previous petrol station was 200 kilometres back, but

the word on the Al-Uwaynat street (it only has one) was that there 'probably

was' petrol 100 kilometres further south in Ghat, the last settlement

before the Algerian and Niger borders. So we kept on down the asphalt

road to Ghat, and - eventually - there was. We also filled up with water

here - we could really only carry what we needed for drinking and cooking,

so we all had to get used to washing with less than a pint of water

per day per person. By detouring to Ghat we were on the western side

of the Tadrart Acacus mountains, whereas the archaeology is all on the

eastern side, so we had to make a long detour south as far as the border

zone with Algeria, then cross the spectacular Takhakhouri Pass (Figure

2), the vehicles repeatedly having to gain height up every incline crawling

through slushy 'fesh-fesh' sand, and falling back repeatedly, before

finally making the summit.

The Tadrart Acacus

has been the focus of research by Italian scholars over many decades,

the rock art studies being pioneering especially by Fabrizio Mori (1960,

1965). More recently this work has been augmented by some outstanding

inter-disciplinary survey and excavation programmes, most recently by

Mauro Cremaschi and Salvino di Lernia in and around the Wadi Teshuinat

(Cremaschi and di Lernia, 1998). The traditional theory about the transition

from foraging to herding in the Sahara has been that Neolithic colonists

spread westwards from the Nile valley c.4000 BC, bringing pottery, domestic

animals and plants with them, but the Italian work, especially in the

Wadi Teshuinat that was the main focus of our visit to the Tadrart Acacus,

demonstrates a very different scenario, of Mesolithic foragers changing

to herding in the context of desiccation (Barker 2002, in press).

Figure 5. A handsome engraving

of an elephant, a typical example of the 'Bubaline' or 'Big Game'

style of rock art in the Tadrart Acacus thought to have been carved

by early Holocene foragers. |

Their palaeoenvironmental

studies have shown how the region (as elsewhere in the Sahara) was ultra-arid

in the late Pleistocene, and effectively uninhabited, but the transition

to the Holocene introduced conditions dramatically wetter than today

- rainfall has been estimated variously at 10-15 times modern levels

- allowing people to colonize the region once more. On the evidence

of excavations in caves such as Uan Afuda, one of the highlights of

our visit (Figure 3), these early Holocene foragers collected grasses

and wild cereals (sorghum and millet), fished, and hunted riverine animals

including crocodile, hippopotamus and turtle and savanna animals such

as large and small antelopes, though the main quarry was the Barbary

sheep. At Uan Afuda di Lernia and Cremaschi have also found extraordinary

evidence for the management of the latter species 1000 years before

the appearance of domestic cattle, sheep and goats. Their evidence is

very convincing: they found clear structural and micromorphological

evidence for stalling, and the Barbary sheep coprolites have partially-ground

grass seeds in them. This remarkable evidence for 'pre-herding herding'

at Uan Afuda coincides with climatic evidence for a sudden onset of

dryness, so the onset of desiccation appears to have been the context

for significant shifts in behaviour.

Figure 6. Hunting a Barbary

sheep - a typical example of Saharan 'Pastoral Neolithic' rock

art in the Wadi Teshuinat. |

There is evidence

of a wetter oscillation in the mid Holocene, but the overall trend was

to aridity, which seems to have been the critical context in which the

indigenous populations developed an increasing commitment to pastoralism.

We visited one of the best known 'Pastoral Neolithic' sites in the Sahara,

Uan Muhuggiag (a few kilometres from Uan Afuda), where excavations by

Mori showed that people were herding domestic cattle, sheep and goats

by the fifth millennium BC, combining pastoralism with hunting, fishing,

and gathering. The site is also notable because Mori found fragments

of painted rock that had fallen from painted images on the walls of

the rock shelter into occupation deposits below dated to about 3000

BC. This association is still one of the best pieces of dating evidence

we have for Saharan 'pastoralist' rock art. The Wadi Teshuinat has examples

(in the hundreds) of all the main styles of Saharan rock art, which

is either engraved/incised into the rock, or painted in reds and whites

(Figure 4). Engravings of big isolated wild animals like elephant (Figure

5), giraffe, rhinoceros, buffalo, and crocodile (the so-called Big Game

or Bubaline phase) are assumed to have been carved by hunters in the

early Holocene humid phase. At the other end of the sequence are painted

images of people using horses, chariots, and camels, and recognisable

signs of Egyptian-type culture, generally thought to be of Garamantian

date. In between is the rest of the art, consisting of carvings and

especially paintings of herding and hunting scenes made by the forager-herder

peoples of the Sahara between c.5000 and 1000 BC. They clearly are 'scenes',

too, like the Wadi Teshuinat image of a Barbary sheep being pursued

by dogs and hunters (Figure 6).

Figure 7. An engraved scene

of a herd of cattle, typical of Saharan 'Pastoral Neolithic' rock

art in the Wadi Mathendusc. |

From the Tadrart

Acacus we travelled eastwards across the Erg Uan Kasa sand sea (another

desert campsite) and then crossed the Messak Settafet, a featureless

rock-strewn upland covered in tyre-puncturing rubble and - in enormous

profusion - prehistoric stone tools (we had ten punctures in the total

trip, in fact). The Messak Settafet is cut by numerous wadi channels,

most of which contain examples of engraved rock art, but the main focus

of our visit was the best known and most spectacular collection, in

the Wadi Mathendusc. The Messak was part of the seasonal grazing schedule

of Neolithic pastoralists, who carved hunting and herding scenes on

major exposed rock faces quite unlike the rather secretive locations

of the Tadradt Acacus paintings. On our last two days in Fezzan we saw

fine carvings of herds of cattle (Figure 7) and sheep, including milking

scenes, and of wild animals like ostriches and giraffes being caught

in enclosures or trapped with thongs attached to heavy rocks - hundreds

of these 'trapping stones' still litter the Messak.

Figure 8. The Society's intrepid

Libya Study Tour group. Our principal lecturer David Mattingly

is in the front row on the right. |

Visiting the

National Museum (opened specially for us) on the last morning before

the flight home, it was clear how much of the best of Libya's desert

archaeology we had managed to pack into our short week. We saw wonderful

archaeology that is still visited by very few Europeans, and spectacular

and varied desert scenery. We crossed some of the most demanding vehicle

terrain in the world, which even with all the support of modern technology

is still very challenging. The Society's members (Figure 8) proved wonderfully

intrepid campers and travellers, and delightful companions. Our Libyan

guides and drivers were enormous fun as well as doing everything to

keep us safe, always totally at ease in what was a very alien environment

to most of our group. (Well versed in European sensitivities, our lead

driver carefully slaughtered and gutted our last night's supper out

of sight behind his vehicle at the final desert camp. And that was after

we had thrashed around the desert in darkness for a couple of hours

looking for the kitchen truck that had set up camp behind the wrong

sand dune!) I am sure I speak for all the Society's members on this

memorable Study Tour that it was a privilege to be in their desert,

in their company.

Graeme Barker,

University of Leicester,

(President, Prehistoric Society)

|

gba@le.ac.uk |

Reference

Barker, G., 2002, in press, 'Transitions to farming and pastoralism

in North Africa', in C. Renfrew and K. Boyd (eds) Examining the

Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis, Cambridge, McDonald Institute.

Cremaschi, M., and di Lernia, S., 1998, eds, Wadi Teshuinat: Palaeoenvironment

and Prehistory in South-western Fezzan (Libyan Sahara), Florence,

Insegna del Giglio.

Mattingly, D., 2000, 'Twelve thousand years of human adaptation in

Fezzan (Libyan Sahara), in G. Barker and D. Gilbertson, eds, The

Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin, London, Routledge,

One World Archaeology 39, pp. 160-79.

Mori, F., 1960, Arte Preistorica del Sahara Libico, Rome, De

Luca.

Mori, F., 1965, Tadrart Acacus, Turin, Einaudi.

|