The job ladder in the age of inflation

29 May 2022

Fabien Postel-Vinay argues that unemployment is not the only measure of labour market “slack”, but when it comes to forecasting inflation, it might not even be the best.

Inflation is back in the headlines, with its consequences for living standards and inequality all too well known. Keeping inflation in check is the primary objective of monetary policy, the conduct of which is the main mission of Central Banks. The Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey did little to endear himself to the public by suggesting that people ought to “think and reflect” before asking for pay rises in response to inflation.

One of the longest standing guiding principles of monetary policy is the idea of an inverse short-run relationship between the rates of unemployment and inflation, generically referred to as the Phillips curve.

The “original” Phillips curve – the inverse relationship between nominal wage changes and unemployment in the pre-WW2 UK economy described in a 1958 article by New Zealand-born economist William Phillips – is an empirical regularity. Its simplest theoretical interpretation is that low unemployment signals scarcity of labour, hence upward pressure on its price (the nominal wage).

The more specific narrative underlying more recent macroeconomic models is as follows. When the economy is expanding, firms post many vacancies and the unemployed have an easy time finding new jobs. Unemployment thus declines, while employed workers have a strong bargaining position, and wages rise (although this may happen gradually due to infrequent bargaining).

However, unemployment, is not the only measure of labour market “slack”, and from the perspective of forecasting inflation, it might not even be the best.

In an ongoing research programme, Giuseppe Moscarini (Yale University) and myself advocate shifting emphasis away from unemployment and towards the (mis)allocation of employment on a “job ladder” as the relevant indicator of slack to predict inflation.

Using data from the United States, we found that the rate at which workers move from job to job – the “job switching” rate – has a significant positive relationship with contemporaneous nominal wage inflation, even for stayers who do not switch jobs, over and above any negative relationship between inflation and unemployment.

In fact, we even provide evidence that, once the effect of the job switching rate is factored in, neither the unemployment rate nor the job finding rate from unemployment have any significant co-movement over time with nominal wage inflation.

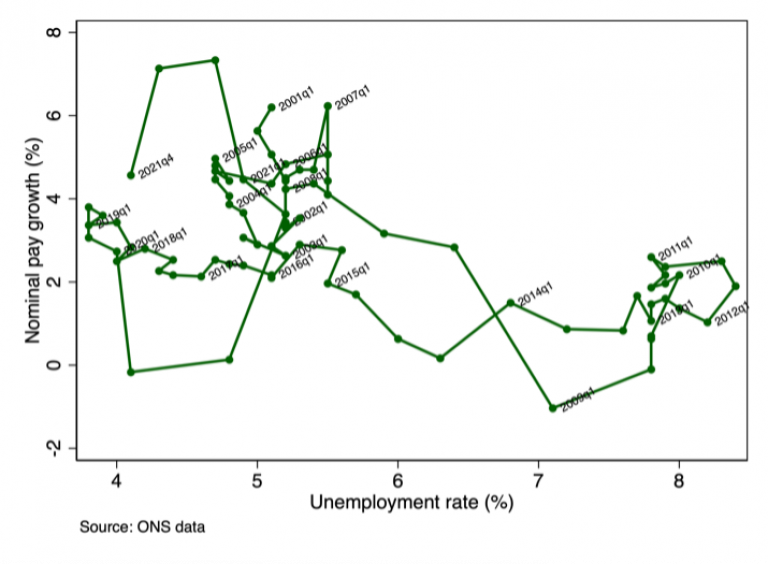

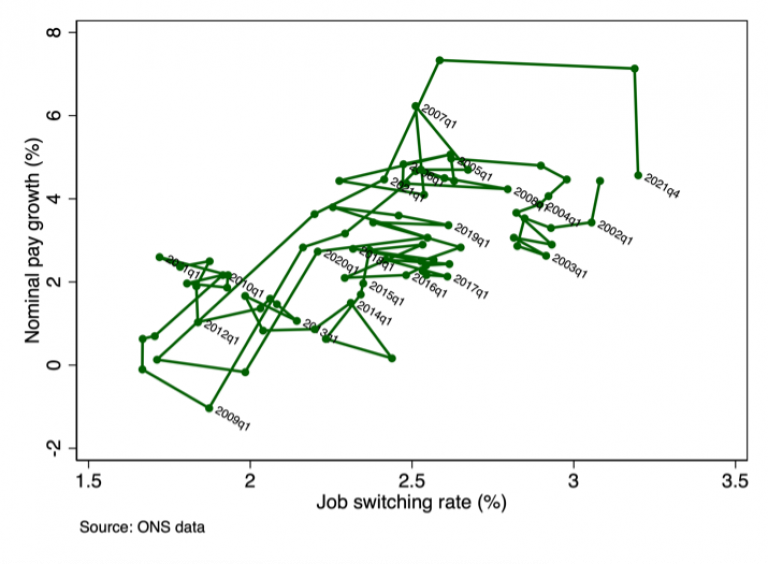

UK data paints a similar picture (Postel-Vinay and Sepahsalari, 2021). Figures 1 and 2 below provide a simple illustration of the strength of the correlation of nominal wage growth with unemployment and the job switching rate, respectively.

Figure 1: The UK Phillips curve, 2001-2021

Figure 2: Wage inflation and the job switching rate in the UK

The strong association between wage inflation and the job switching rate is natural under an alternative “job-ladder” view of labour markets.

Workers’ bargaining power derives not from their outside option of unemployment, but from their ability to receive outside offers.

Outside offers can either be accepted, moving workers up a job ladder, leading to less mismatch and higher aggregate productivity, or matched and declined, pushing wages up and representing, for the employer, a cost-push shock.

The latter outcome is more likely after a sufficiently long aggregate expansion, when workers have been moving up the ladder for a while and become more difficult to poach. In that case, cost pressure builds and, with a lag due to price inertia, eventually manifests itself as price inflation.

We thus claim that competition for the employed, not the unemployed, transmits aggregate shocks to wages, and that the distinction is important, mainly because these two types of competition point to two different observable proxies of slack to guide monetary policy.

Unemployment, ultimately caused by labour market frictions of various kinds, signals poor job creation. Because of the same frictions, however, employed workers are misallocated on a job ladder. The more severe this misallocation, the easier to poach workers away from competitors, the stronger the incentives to job creation, independently of unemployment. Conversely, with less misallocation most outside job offers will be either rejected or matched, causing little employment gains and large wage gains, which are cost-push shocks from the point of view of employers.

Thus, independently of the state of unemployment, the distribution of employment on the job ladder, a very slow-moving statistic, determines job creation and, ultimately, also the pace of job finding from unemployment. Wages do not respond, despite falling unemployment, for quite some time, until few workers are left at the bottom of the ladder, and competition for employed workers intensifies.

Unemployment can thus be seen as the bottom rung of a high job ladder. As such, it is at best an incomplete measure of slack, which must be supplemented by measures of employment misallocation, or symptoms thereof.

It is time that monetary authorities paid attention to the lagged job switching rate.

Dr Fabien Postel-Vinay is Professor of Economics at University College London, a research fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and a Fellow of the Econometric Society.

Close

Close