Research Questions

Word-order alternations may

signal the status of certain phrases in an unfolding discourse.

Here we

investigate the structure of sentences in which a discourse-given constituent

appears in an earlier position in the sentence than it normally would.

This word-order alternation, known as neutral scrambling (NS), is exemplified in the Dutch examples below.

| (1) | a. | Marie | heeft | gisteren | het | boek | gekocht. | |

| Mary | has | yesterday | the | book | bought | |||

| b. | Marie | heeft | het | boek | gisteren | gekocht. | ||

| Mary | has | the | book | yesterday | bought | |||

|

`Mary |

has |

bought |

the |

book |

yesterday' |

In (1a), where 'het boek' (the book) follows 'gisteren' (yesterday), this phrase is interpreted as new information, whereas the order in (1b) requires previous mention of 'the book'.

Our primary objective is to uncover empirical evidence that would allow us to choose between two competing analyses of NS.

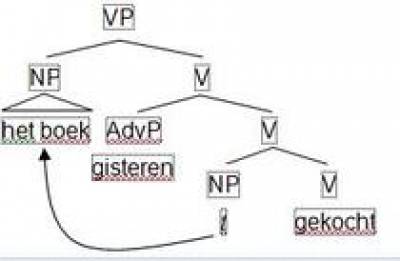

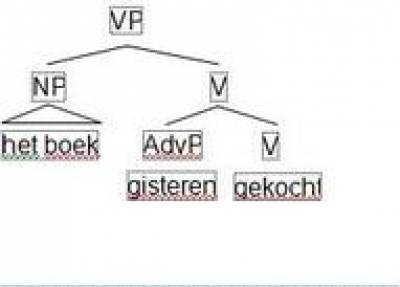

On the first analysis, (1b)

is derived from (1a) by ‘movement’, an operation which leaves behind a ‘trace’

(an unpronounced copy) of the moved constituent, as in (2a).

On the second,

(1a) and (1b) are not related by movement, but differ in how their basic

structures are built: in (1a) 'het boek' combines with the verb to form a

constituent after which 'gisteren' combines with that constituent to create a

yet larger constituent, whereas in (1b) 'het boek' and 'gisteren' combine with

the verb in the opposite order, as in (2b).

On this second analysis, there is no trace of 'het boek' between 'gisteren' and the verb.

| (2) | a. |

|

b. |

|

Research question: Does NS involve movement?

Natural languages differ in the extent to which

they permit NS.

Dutch is representative of a class of languages in which a

discourse-given argument (a subject, object or

indirect object) may undergo NS

across an adjunct (or modifier) but

not across another argument.

German is representative of

a second class of languages, in which NS is

freer and may give rise to reordering of arguments.

This variation is potentially very relevant to the choice between a movement and a base-generation analysis.

There is a strong

cross-linguistic generalization, the thematic hierarchy, concerning the mapping

between semantic roles (agent, theme, etc.) and their structural realization.

For example, an agent is invariably realized higher in the syntactic structure

than a theme.

A base-generation analysis of NS across an adjunct gives rise to

structures that respect the thematic hierarchy.

By contrast, a base-generation

analysis of NS across an argument would imply that the syntactic realization of

arguments may violate this hierarchy under appropriate discourse conditions.

This being the case, we should investigate the possibility that these two variants of NS do not yield to the same analysis and split the general question posed above into two subquestions, to be investigated separately:

Subquestion 1: Does NS across an adjunct involve syntactic movement?

Subquestion 2: Does NS across an argument involve syntactic movement?

Close

Close