Animal model of evolution indicates thick hair mutation emerged 30,000 years ago

15 February 2013

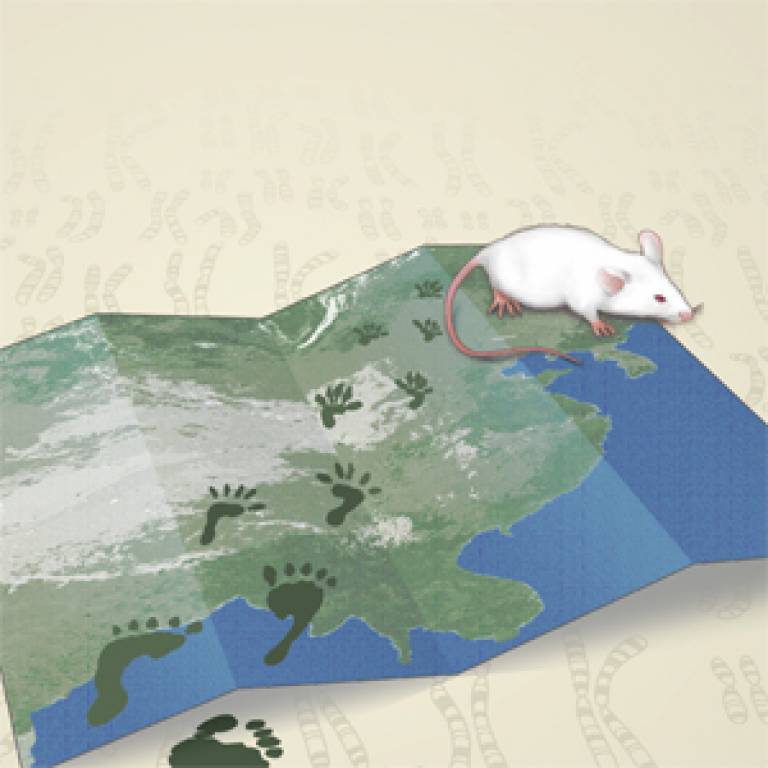

The first animal model of recent human evolution reveals that a single mutation produced several traits common in East Asian peoples, from thicker hair to denser sweat glands, an international team of researchers report.

The team, led by researchers from Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital, Fudan University and University College London, also modelled the spread of the gene mutation across Asia and North America, concluding that it most likely arose about 30,000 years ago in what is today central China.

The findings are reported in the cover story of the 14 February issue of Cell.

"There are three parts to this study," said Professor Mark Thomas, UCL Research Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, and an author on the paper.

"The first links the version of the EDAR gene common in East Asians to a set of traits including thicker hair and a higher density of sweat glands; the second uses computer simulation to identify where and when the mutation is likely to have arisen, and what its selective advantage was likely to be; and the third showed that when the East Asian version of the gene is inserted into a mouse, that mouse exhibited many of the same traits as those it is linked with in humans."

Previous research in Pardis Sabeti's lab at Harvard University had identified the mutation as a strong candidate for positive selection. That is, evidence within the genetic code suggested the mutant gene conferred an evolutionary advantage, though what advantage was unclear.

The mutation was found in a gene for ectodysplasin receptor,

or EDAR, part of a signalling pathway

known to play a key role in the development of hair, sweat glands and other

skin features. While human populations in Africa and Europe had one, ancestral,

version of the gene, most East Asians had a derived variant, EDARV370A, which studies had linked to

thicker scalp hair and an altered tooth shape in humans.

There are three parts to this study. The first links the version of the EDAR gene common in East Asians to a set of traits including thicker hair and a higher density of sweat glands; the second uses computer simulation to identify where and when the mutation is likely to have arisen, and what its selective advantage was likely to be; and the third showed that when the East Asian version of the gene is inserted into a mouse, that mouse exhibited many of the same traits as those it is linked with in humans.

Professor Mark Thomas

The ectodysplasin pathway is highly conserved across vertebrates - the same genes do similar things in humans and mice and zebrafish. For that reason, and because its effects on skin, hair and scales can be observed directly, it is widely studied.

This evolutionary conservation led Yana Kamberov, one of two first authors to reason that EDARV370A would exert similar biological effects in an animal model as in humans. Kamberov developed a mouse model with the exact mutation of EDARV370A - a difference of one DNA letter from the original, or wild-type, population. That mouse manifested thicker hair, more densely branched mammary glands and an increased number of sweat glands.

"This not only directly pointed us to the subset of organs and tissues that were sensitive to the mutation, but also gave us the key biological evidence that EDARV370A could have been acted on by natural selection," said Kamberov.

The findings prompted the team to look for similar traits in human populations. When co-first author Sijia Wang and the team including collaborators at Fudan University examined the fingertips of Chinese volunteers at colleges and farming villages, they found that the sweat glands of Han Chinese, who carry the derived variant of the gene, were packed about 15 percent more densely than those of a control population with the ancestral variant.

At the same time, collaborators at UCL were working to zero in on when and where the mutation arose.

Computer models suggest that the derived variant of the gene

emerged in central China between 13,175 and 39,575 years ago, with a modal

(most likely) estimate of 30,925 years.

Researchers concluded the derived variant is at least 15,000 years old, predating the migration from Asia by Native Americans, who also carry the mutation.

That time span suggests that different traits could have been under selection at different times. The mutation's many effects only complicate the question. If changes to the sweat glands conferred an advantage in new climates - one of the theories the researchers plan to explore further - changes to hair and to mammary glands could have conferred other advantages at other times.

Professor Thomas said: "We don't know which of the many traits were advantageous in the past. It is easy to imagine that thicker hair, tooth shape, more sweat glands or some other associated skin features could have increased fitness, but for quite different reasons."

Dr Pascale Gerbault, a PhD student in Professor Thomas's group, and co-author of the paper said: "What seems unlikely is that the same traits were advantageous throughout the whole of the last 30,000 years; prior to 10,000 years ago the climate was cold and highly variable, but for the last 10,000 years it has been much warmer and relatively stable."

She added: "So perhaps one trait was favoured when it was colder and another when it became warmer. Maybe one of the less visible traits was selected early on, leading to a rise in the frequency of a more visible trait like thicker hair, which was later selected as a cultural preference."

Sijia Wang - a former UCL PhD student - intends to focus on that question in his new role, as a Max Planck independent research group leader in dermatogenomics at Chinese Academy of Sciences - Max Planck Partner Institute for Computational Biology in Shanghai.

By leveraging the power of diverse fields, the team is piecing together the foundation for understanding how selected mutations like EDARV370A have impacted human diversity. But, the authors say, this is only the beginning.

"These findings point to what mutations, when, where and how," said Daniel Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University and a co-senior author on the study. "We still want to know why."

UCL media contact: Clare Ryan

Links:

UCL Research Department of Genetics, Evolution & Environment

Professor Mark Thomas

Full paper in Cell (£)

Close

Close