Tackling early socioeconomic inequalities as important as encouraging smoking cessation

19 November 2013

Although health behaviours such as smoking are directly linked to the majority of early deaths in the UK, tackling these individual factors fails to address the underlying cause.

To get

to the root of the problem, childhood deprivation must be addressed because it

promotes damaging health behaviours in adult life. So say researchers from UCL

in a study published in the Journal of

Epidemiology & Community Health.

To get

to the root of the problem, childhood deprivation must be addressed because it

promotes damaging health behaviours in adult life. So say researchers from UCL

in a study published in the Journal of

Epidemiology & Community Health.

The study aimed to quantify the effects of early life circumstances on people's propensity to smoke, and the link between lower social status and increased risk of early death.

Professor Eric Brunner (UCL Department of Epidemiology and Public Health), senior author of the research, says: "We set out to understand whether the risk of early death is passed from one generation to the next by social and economic disadvantage. Our research, based on a cohort of babies born in 1946, shows that inequalities in childhood and early adult life directly impact on social inequalities in mortality in later life.

Early life circumstances clearly have a huge effect on the health behaviours people exhibit into adulthood.... Our work provides evidence that social inequalities in health will persist unless prevention strategies tackle the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage and risk.

Professor Eric Brunner, UCL Epidemiology and Public Health

"What we found was that whether people smoke or not accounts for a significant amount of the social difference in premature mortality," continues Professor Brunner. "However, when we factor in people's early life circumstances, the independent explanatory power of smoking behaviour reduces from 51 per cent to 28 per cent. The difference is explained by the social and economic inequalities people experienced in their formative years.

"Early life circumstances clearly have a huge effect on the health behaviours people exhibit into adulthood. For example, many teenagers in the study started smoking, and childhood advantage predicted successful quitting. This pattern of quitting leads to the familiar social patterning of smoking in middle age. Our work provides evidence that social inequalities in health will persist unless prevention strategies tackle the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage and risk."

The researchers analysed data from 2,132 participants who were born in 1946 and followed to the age of 66 as part of the 1946 Birth Cohort (MRC National Survey of Health and Development). Socioeconomic circumstances were measured during childhood (based on the father's social class when the participant was aged 4, and the level of maternal education when the participant was aged 6) and at the age of 26 (based on the participant's educational attainment, home ownership and the social class of their head of household).

Lead author Ingrid Giesinger says: "Differences in childhood and early adult circumstances are underlying causes of social inequalities in both adult health behaviours and mortality in the immediate post-war generation. Policies focused only on adult health behaviours do not address the socially patterned causes of these behaviours, or the independent role played by these causes in social inequalities in health."

David Buck, Senior Fellow at health think-tank The Kings Fund, says: "We welcome this study which demonstrates how important early life experiences are directly to our long-term health, and how this is reinforced through shaping our health behaviours which then track through to adulthood and early death. This strengthens the case for increased investment in narrowing inequalities in early childhood experience, as well as measures to support quitting smoking and other damaging health behaviours in adults."

-Ends-

Additional information:

Previous studies have investigated the 'socioeconomic gradient in mortality' (i.e. the link between lower social status and increased risk of early death). One recent study demonstrated that when people's behaviour over an extended period of time (24 years) is factored in, almost three quarters (72%) of the social gradient can be explained by smoking, drinking, diet and exercise. However, what this earlier work failed to address is the impact of poor circumstances in childhood and early adulthood on later health behaviours.

Media contact: David Weston

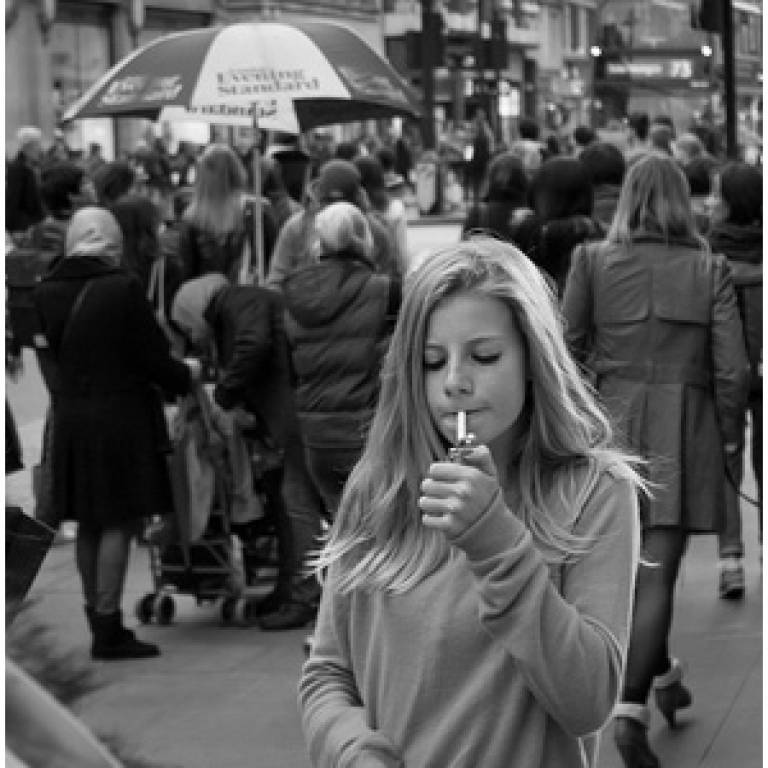

Image caption: Teenage smoker, from M Hooper on Flickr

Links:

Close

Close