Colombian guerrillas help UCL scientists locate literacy in the brain

15 October 2009

UCL scientists have redefined their understanding of the key regions of the brain involved in literacy.

The unique study of former guerrillas in Colombia, funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, enabled researchers to see how brain structure changed after learning to read.

In today's edition of Nature, Professor Cathy Price (UCL), a member of the research team from the UK, Spain and Colombia, describes a study working with an unusual cohort: former guerrillas in Colombia who are re-integrating into mainstream society and learning to read for the first time as adults.

"Separating out changes in our brains caused by learning to read has so far proven almost impossible because of other confounding factors," explained Professor Price, (UCL Neuroscience). "Working with the Colombia guerrillas has provided a unique opportunity to see how the brain develops when reading skills are acquired."

The researchers examined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the brains of 20 guerrillas who had completed a literacy programme in their native tongue (Spanish) in adulthood. They compared these to scans of 22 similar adults before beginning the same literacy programme. The results revealed which brain areas are allocated to reading, prompting new research in the UK on how these regions are functionally connected in adults who learn to read in childhood.

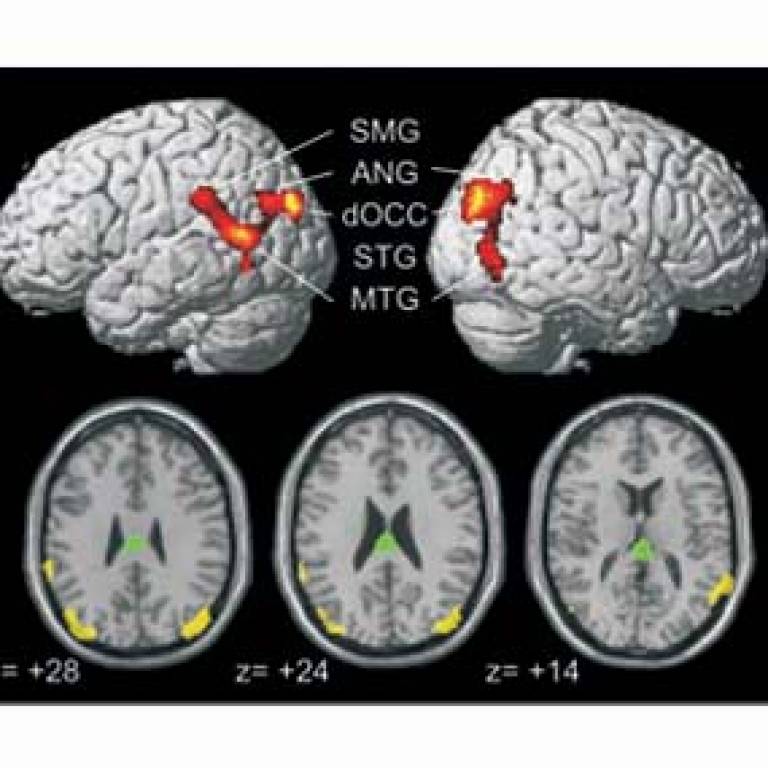

The researchers found that for those participants who had learnt to read, the density of grey matter (where the 'processing' is done) was higher in several areas of the left hemisphere of the brain. As might be expected, these were the areas that are responsible for recognising letter shapes and translating the letters into speech sounds and their meanings. Reading also increased the strength of the 'white matter' connections between the different processing regions.

Particularly important were the connections to and from an area of the brain known as the angular gyrus. Scientists have known for over 150 years that this brain region is important for reading, but the new research has shown that its role had been misunderstood.

Previously, it was thought that the angular gyrus recognised the shapes of words before finding their sounds and meanings. In fact, the researchers showed that the angular gyrus is not directly involved in translating visual words into their sounds and meanings. Instead, it supports this process by providing predictions of what the brain is expecting to see.

"The traditional view has been that the angular gyrus acts as a 'dictionary' that translates the letters of a word into a meaning," explained Professor Price. "In fact, we have shown that its role is more in anticipating what our eye will see - more akin to the predictive texting function on a mobile phone."

The findings are likely to prove useful for researchers trying to understand the causes of the reading disorder dyslexia. Studies of dyslexic people have shown regions of reduced grey and white matter in regions that grow after learning to read. This new study therefore suggests that some of the differences seen in dyslexia may be a consequence of reading difficulties rather than a cause.

Image above right: the regions where the brain had grown after learning to read

Related news

UCL study: subliminal messaging 'more effective when negative'

Close

Close