Why bad experiences are remembered out of context

10 May 2016

Bad experiences can cause people to strongly remember the negative content itself but only weakly remember the surrounding context, and a new UCL study funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust has revealed how this happens in the brain.

The study, published in Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, has important implications for understanding conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

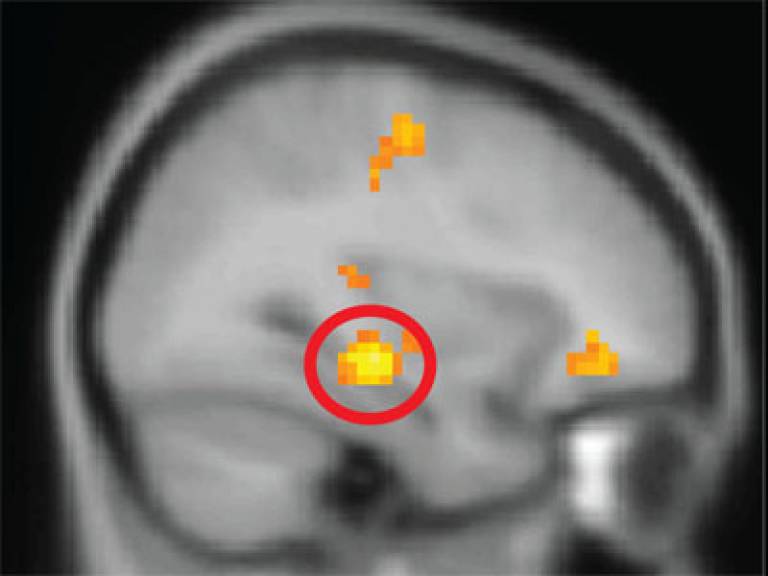

"When we presented people with negative content alongside neutral content, the brain areas involved in storing the negative content were more active while those involved in storing the surrounding context were less active," explains lead author Dr James Bisby (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience). "When we experience a new event, we not only store the contents of the event in memory, such as the people we met, but we also form associations with the context in which the event took place. The hippocampus is a crucial brain region for forming these associations so that all aspects of the event can be retrieved together and placed in the appropriate context, and it was here that we saw reduced activity."

The experiment involved 20 volunteers who were placed in an MRI scanner and shown pairs of pictures to remember. Some of these pictures involved negative content such as a badly injured person. Participants' memory was then tested by showing them images and asking if they had seen that image before. If they had, they were asked whether they could remember the other picture that it had been presented with.

Participants were better at recognising negative pictures than neutral ones, which was reflected by increased activity in the amygdala, a part of the brain used for processing emotional information. However, they were worse at remembering which other pictures appeared alongside negative ones, reflecting reduced activity in the hippocampus.

"The imbalance between item memory and associative memory could lead to strong but fragmented memory for the traumatic content of an event, without the surrounding information that would put it in the appropriate context," says senior author Professor Neil Burgess, Director of the UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience. "People who have suffered a traumatic event can experience vivid and distressing intrusive images from it, as in post-traumatic stress disorder. These intrusive images might occur due to strengthened memory for the negative aspects of the trauma that are not bound to the context it occurred in. This may be the mechanism behind 'flashbacks', where traumatic memories are involuntarily re-experienced as if they are happening in the present."

Links

- Full paper in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience

- Professor Neil Burgess's academic profile

- Dr James Bisby's academic profile

- UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience

- UCL Psychology and Language Sciences

- UCL Brain Sciences

Image

- Hippocampus (courtesy of Professor Neil Burgess)

Media contact

Harry Dayantis

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3844

Email: h.dayantis[at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close