Solar Orbiter shows the Sun as never seen before

18 May 2022

Solar Orbiter, a European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft carrying instruments proposed, designed and built at UCL, has had its closest approach yet to the Sun, providing breathtaking images and movies of the solar poles, of powerful flares, and of a curious solar "hedgehog".

The close approach to the Sun, known as perihelion, took place on 26 March. The spacecraft was inside the orbit of Mercury, at about one-third the distance from the Sun to the Earth, and its heatshield was reaching around 500°C. But it dissipated that heat with its innovative technology to keep the spacecraft safe and functioning.

Solar Orbiter carries ten science instruments, all working together in close collaboration to provide unprecedented insight into how our local star “works”. UCL scientists have a leading role in two of them – the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), a suite of telescopes providing images of the hot and cold layers of the Sun’s atmosphere and corona, and the Solar Wind Analyser (SWA).

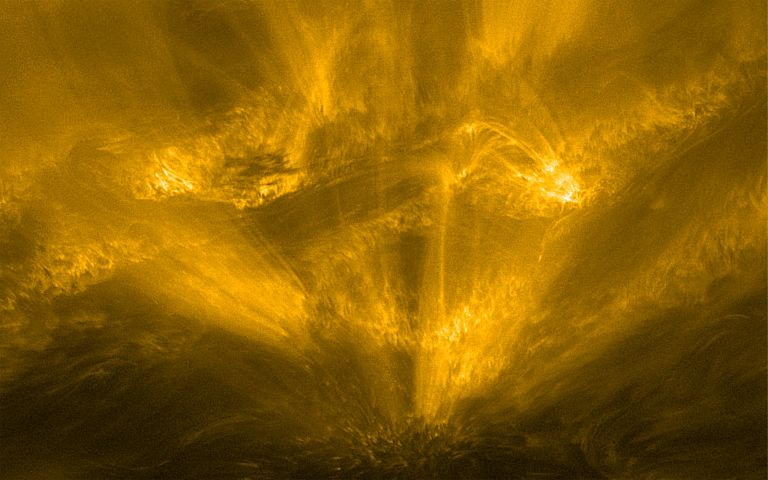

One eye-catching feature observed by the EUI instrument during this perihelion has been nicknamed “the hedgehog” (image, below,). It stretches 25,000 kilometres across the Sun and has a multitude of spikes of hot and colder gas that reach out in all directions.

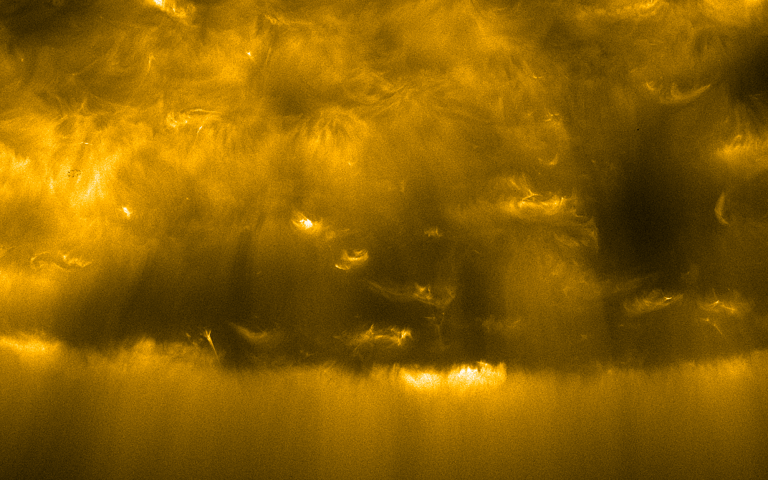

The EUI instrument also returned its highest resolution image ever of the Sun’s south pole, recorded on 30 March 2022, just four days after the spacecraft passed its closest point yet to the Sun.

Dr David Long (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory), Co-Principal Investigator on the EUI, said: “These movies and images are spectacular, and it’s amazing to think that this is only a fraction of the observations made by Solar Orbiter during the first science observing period.

“It’s incredible to see all of the different instruments working together and to be able to track flows and eruptions on the Sun and how they connect to material passing over the spacecraft.

Regarding the south pole image, Dr Long added: “We’re starting to see constant brightenings and eruptions with really high resolution in the poles. As the orbit of Solar Orbiter moves out of the ecliptic plane towards the poles we’ll start to see this in more detail, but already we can see just how much is going on there. Similarly, with the ‘hedgehog’ feature, which is just beautiful. It’s amazing to see these really small-scale flows and brightenings along the magnetic field lines with such high resolution.”

The task now for the EUI team is to understand what they are seeing. This is no easy task because Solar Orbiter is revealing so much activity on the Sun at the small scale. Having spotted a feature or an event that they can’t immediately recognise, they must then dig through past solar observations by other space missions to see if anything similar has been seen before.

Joining the dots

By combining data from remote-sensing instruments that look at the Sun with data from in-situ instruments, such as the Solar Wind Analyser, that monitor the conditions around the spacecraft, scientists are able to “join the dots” from what they see happening at the Sun, to what Solar Orbiter “feels” at its location in the solar wind millions of kilometres away.

The closer the spacecraft gets to the Sun, the finer the details the remote sensing instrument can see. As luck would have it, the spacecraft also soaked up several solar flares and even an Earth-directed coronal mass ejection, providing a taste of real-time space weather forecasting, an endeavour that is becoming increasingly important because of the threat space weather poses to technology and astronauts.

Coming soon

The perihelion is just a taste of what is to come. Already the spacecraft is racing through space to line itself up for its next – and slightly closer – perihelion pass on 13 October at 0.29 times the Earth-Sun distance. Before then, on 4 September, it will make its third flyby of Venus.

Solar Orbiter has already taken its first pictures of the Sun’s largely unexplored polar regions but much more is still to come.

On 18 February 2025, Solar Orbiter will encounter Venus for a fourth time. This will increase the inclination of the spacecraft’s orbit to around 17 degrees. The fifth Venus flyby on 24 December 2026 will increase this still further to 24 degrees, and will mark the start of the “high-latitude” mission.

In this phase, Solar Orbiter will see the Sun’s polar regions more directly than ever before. Such line-of-sight observations are key to disentangling the complex magnetic environment at the poles, which may in turn hold the secret to the Sun’s 11-year cycle of waxing and waning activity.

Links

- ESA Solar Orbiter

- ESA story

- Dr David Long’s academic profile

- Professor Chris Owen’s academic profile

- UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

Images

- Top: Solar Orbiter’s highest resolution image ever of the Sun’s south pole

The Sun’s south pole as seen by the ESA/NASA Solar Orbiter spacecraft on 30 March 2022, just four days after the spacecraft passed its closest point yet to the Sun. These images were recorded by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) at a wavelength of 17 nanometers. Many scientific secrets are thought to lie hidden at the solar poles. The magnetic fields that create the great but temporary active regions on the Sun get swept up to the poles before being swallowed back down into the Sun where they are thought to form the magnetic seeds for future solar activity. The lighter areas of the image are mostly created by loops of magnetism that rise upwards from the solar interior. These are called closed magnetic field lines because particles find it hard to cross them, and become trapped, emitting the extreme ultraviolet radiation that EUI is specially designed to record. The darker areas are regions where the Sun’s magnetic field lies open, and so the gasses can escape into space, creating the solar wind. The colour on this image has been artificially added because the original wavelength detected by the instrument is invisible to the human eye. Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Tea

- Middle: Solar Orbiter’s solar hedgehog

The intriguing feature in the bottom third of the image, below the centre, has been nicknamed the solar hedgehog. At present no one knows exactly what it is or how it formed in the Sun’s atmosphere. The image was captured on 30 March 2022 by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) at a wavelength of 17 nanometres. Just days earlier, Solar Orbiter had passed through its first close perihelion. At just 32 percent the distance of the Earth from the Sun, this placed the spacecraft inside the orbit of the inner planet Mercury. Being closer to the Sun than any previous solar telescope has allowed EUI to take exquisitely detailed images of the solar atmosphere. These are revealing the Sun as never before, and have shown a multitude of intriguing features such as the hedgehog, which although classed as a small-scale feature still measures some 25 000 km across, making it around twice the diameter of the Earth. The gases shown in this image have a temperature of around one million degrees. The image has been colour coded because the original wavelength detected by the instrument is invisible to the human eye. Credits: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team

Media contact

Mark Greaves

T: +44 (0)7990 675947

E: m.greaves [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close