Human immune system can control re-awakened HIV, suggesting 'kick and kill' cure is possible

13 April 2015

The human immune system can handle large bursts of HIV activity and so it should be possible to cure HIV with a 'kick and kill' strategy, finds new research led by UCL, University College London Hospitals (UCLH) NHS Foundation Trust, the University of Oxford and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The 'kick and kill' strategy aims to cure HIV by stimulating the immune system with a vaccine, then re-awakening dormant HIV hiding in white blood cells with a chemical 'kick' so that the boosted immune system can identify and kill them.

While this approach is promising in theory, it was previously unclear whether the human immune system would be able to control HIV following full-blown reactivation of the virus. The new research, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, demonstrates that this is possible using a single patient case study.

"Our study shows that the immune system can be as powerful as the most potent combination drug cocktails," explains study co-author and Wellcome Trust fellow Dr Ravi Gupta (UCL Infection & Immunity). "We're still a long way from being able to cure HIV patients, as we still need to develop and test effective vaccines, but this study takes us one step closer by showing us what type of immune responses an effective vaccine should induce."

The study looked at a single 59 year old man in London who was an 'elite controller', meaning that his immune system could control HIV for a long time without needing treatment. Elite controllers, who make up 0.3% of HIV patients, eventually require treatment to prevent progression to AIDS but they can go a lot longer without treatment because their immune systems are more active against HIV.

The patient in the study had both HIV and myeloma, a cancer of the bone marrow. The bone marrow produces white blood cells, including those that help to control HIV. To treat the patient's myeloma, his bone marrow was completely removed and replaced using his own stem cells. When the bone marrow was removed, the immune system was severely impaired, allowing the HIV to re-activate and replicate. This caused the level of virus in his bloodstream to rise from fewer than 50 copies per millilitre to approximately 28,000 copies per ml before immune function returned.

When the patient's immune function returned about two weeks after the transplant, the levels of HIV in his bloodstream rapidly fell. His immune system reduced HIV levels at a similar rate to the most powerful treatments available, bringing them back down to 50 copies per ml within six weeks.

"By measuring the strength of the immune system required to keep this virus under control in this rare individual, we have a better idea of the requirements for successful future treatment," says co-author Professor Deenan Pillay (UCL Infection & Immunity, and now also Director of the Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, in South Africa). "We also managed to identify the specific immune cells that fought the infection. This is a single patient study, but nevertheless it is often the unusual patients who help us to understand the HIV disease process."

The patient was not given anti-HIV medication in this study due to concerns about side-effects affecting the myeloma treatment and low initial levels of HIV in his bloodstream. It is possible that an equally strong immune response in combination with powerful drugs could have cured the HIV completely, however this is far from certain.

"We need to be cautious in interpreting observations from a single subject," says Dr Nilu Goonetilleke, who began working on the study at the University of Oxford and is now at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "However, demonstration even from a single subject, that our immune system can rapidly control HIV-1 tells us a lot about the types of immune responses we should target and augment through vaccination."

Dr Gupta adds: "Drugs to stimulate reactivation of dormant HIV are still imperfect, and we do not know if they would be able to flush out all of the HIV from the body. Likewise, it remains to be seen whether a vaccine could enable a normal HIV patient's immune system to kill HIV with the full strength of an elite controller. Our study is a proof of principle and the results are promising, but it is unlikely to lead to a cure for at least a decade.

Links

-

Research paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases

- Dr Ravi Gupta's academic profile on IRIS

- Professor Deenan Pillay's academic profile on IRIS

- UCL Infection & Immunity

- University of Oxford

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Wellcome Trust

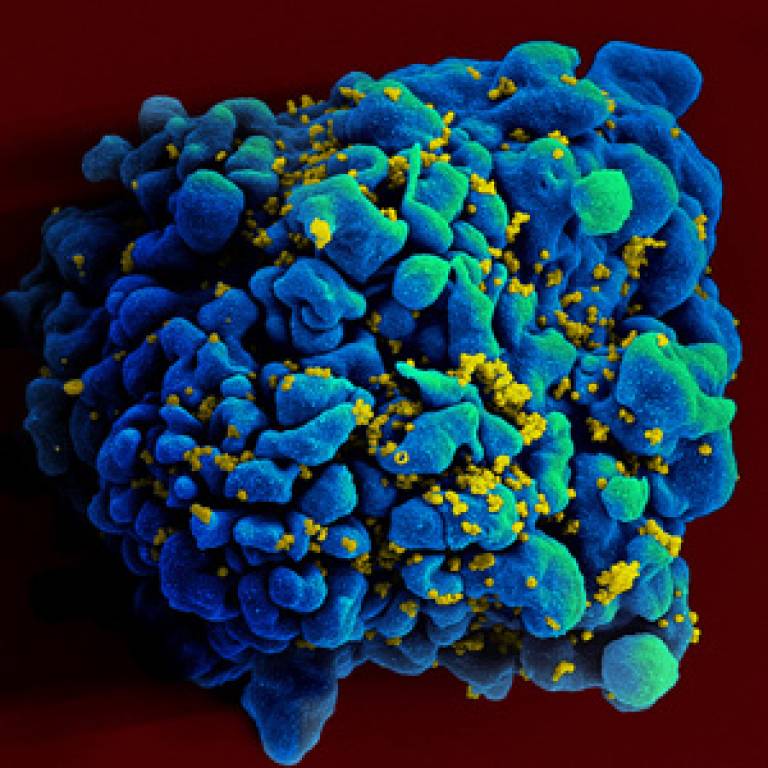

Images

- Scanning electromicrograph of an HIV-infected H9 T cell (courtesy of NIAID on Flickr)

Media contact

Harry Dayantis

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3844

Email: h.dayantis [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close