Award-winning book on France and England's aggressively intimate relationship

21 February 2011

The quintessentially English author Chaucer is more French than most of us realise, argues Ardis Butterfield (UCL English) in her award-winning book The Familiar Enemy (Oxford University Press).

Professor Butterfield has won the 2010 Gapper Prize for her rare illumination of the literary aspect of the Hundred Years War. She suggests that a modern understanding of what 'English' might have meant during this turbulent period cannot be separated from 'French'.

In the words of the competition judging panel: "The book's chronological and cultural scope, and its intellectual ambitions, are exceptional. Butterfield mobilizes a profound and wide-ranging knowledge of the field across both English and French studies, drawing not only on literary texts but also on documents from fields such as education and commerce... This is nevertheless an eminently readable study...No discipline could ask for more."

Professor Butterfield elaborates below on the far-reaching implications this has today for our understanding of the English and French peoples, and their languages.

"The relationship between England and France, soeurs ennemies, has been praised, mocked, fought for and resisted, ceaselessly discussed, and self-consciously lived, for longer than any other Western axis.

It makes an irresistible claim to be studied for what it can tell us about nation. For over a millennium, in a stable geographical tension either side of a narrow sleeve of sea, the English and the French have provided a model of how people identify with one another while also preserving an autonomous space.

The most significant period in this long stretch of time was undoubtedly the Hundred Years War: not only did it bring to the surface the fundamental antagonisms of their familial relationship, it also brought with it a huge experiential and written trace through which the medieval era has uniquely influenced the political constructs of the modern western world.

No modern version of nationhood is complete without an understanding of how the English and the French have lived and articulated their mutual history during, and as a result of, the long medieval war.

Two images, one verbal and English, one pictorial and French, show the depths of this fraught intimacy. For an Anglophone, its image is overwhelmingly formed by Shakespeare's Henry V crying 'we few, we happy few, we band of brothers' at Agincourt, and the Black Prince watched from on high by his father 'up in the air, crowned with the golden sun' (II, 4: 58).

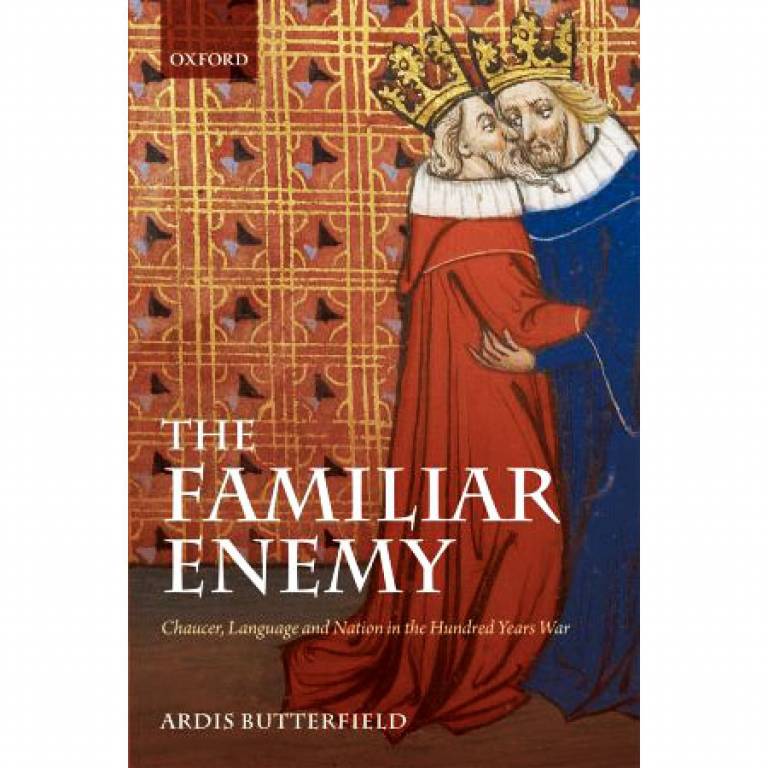

A late fourteenth century illustration (shown on the cover) of the Chroniques de France, a history commissioned by Charles V, presents, by contrast, a deeply ambiguous fraternal embrace. Edward III and Philippe VI, at the very moment where Edward swears fealty, are shown locked close and cheek to cheek. This gesture, visually so full of affection, proclaims the start of war.

It seems incumbent on a medievalist to seek to convey that understanding. Many distinguished historians have undertaken that task. Yet, perhaps surprisingly, there still remains space for the literary critic to attempt his or her own explication of the war. For despite its historical and cultural prominence, the Hundred Years War has remained very much on the margins of literary history. Chaucer, the figure who dominates that history from an English perspective, is rarely viewed as a poet of war.

The war thus constitutes the strangely undiscussed epicentre of the relationship between English and French writers in this period. Anglo-French conflict was not only a constant fact or threat throughout Chaucer's lifetime, but it also shaped the way people thought, conducted business, kept records, sought social rewards, and wrote prose and poetry. One purpose of this book is (still uneasily) to bring war back into view for literary history, but not so much to understand war itself as to grasp how it affected writing and the imaginative intellect.

What has drawn me to this particular conflict is that it has exemplary but also peculiar characteristics. This is not a war of nation-states where the boundaries of aggression are clearly marked, but a feudal and familial one where the two sides are tightly bound by lengthy and intimate identifications, through marriage and territorial possession. Above all, they are linked and separated by language.

In order to think through the nature of the Anglo-French relationship we need to take account of this vital fact, that the two cultures shared a language for four centuries, indeed, one might argue, that they share it still. From before the Norman Conquest, when Emma of Normandy was wife first to Ethelred and then Canute, kings of England married French-speaking queens. From William of Normandy to Edward IV, with the single exception of Richard the Lionheart, they did so invariably.

In specific but overlapping social and intellectual circles until the 1420s and 1430s, and in some fields such as law for much longer, French in England was the language of jurisdiction, of official and private correspondence, diplomacy, parliamentary petitions, the Privy Seal, guild documents, administrative registers, business transactions, the Bible, sermons and moral and devotional treatises, history, biography, satire, romance, lyric, science, and medicine.

Before the fifteenth century, the overwhelming majority of books owned and used in England were in Latin and French, a situation which did not change markedly with the development of printing. Among figures associated with the court and Westminster whose booklists survive-Richard II himself, Simon Burley his tutor and later chamberlain, diplomat and Garter Knight, Thomas, Duke of Gloucester (Richard's younger brother) and Thomas's wife, Eleanor Bohun-a total between them of some hundred and thirty books are mentioned: of these over 90 were in French and over 30 in Latin: just four were in English.

The heart of my study concerns what it means to be English and French in the light of this common possession. Sharing a language and a literature crucially confuses a clear sense of distinction between English and French. The world and work of words from the period is thickly coloured by histories of meaning, speaking, and writing that are both English and French, by a use of French that is English as well as French, that is homely and foreign. This, I argue, has profound repercussions for thinking about nationhood, and thinking about language."

- The Familiar Enemy (Oxford University Press)

- Professor Ardis Butterfield

- Society for French Studies Gapper Book Prize 2010

Image: Dustjacket of The Familiar Enemy: Chaucer, Language and Nation in the Hundred Years War by Ardis Butterfield

UCL context

UCL English has, throughout its history, been a pioneer in the study of English language and English literature, from Old English to current literature. Its staff demonstrate a wide breadth of expertise across many literary periods (Medieval, Renaissance, Restoration, Romantic, Victorian and modern) and topics (such as London and American literature) as well as in language, both its history and its modern forms. The Survey of English Usage, based in the department, is an internationally renowned resource for the study of present-day English and a world leader in corpus linguistics.

The R.H. Gapper Book Prize is awarded by the Society for French Studies for a book in the field of French studies, published for the first time in the previous calendar year, by a scholar based in an institution of higher education in the UK or Ireland. The criteria for award of the prize are, broadly, the book's critical and scholarly distinction and its likely impact on wider critical debate.

Close

Close