The genetic secrets that allow Tibetans to thrive in thin air

7 June 2010

Links

pnas.org/" target="_self">Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

pnas.org/" target="_self">Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

A new study pinpoints the genetic changes that enable Tibetans to thrive at altitudes where others get sick.

The online

edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences today reports on the work of an international team involving UCL's Professor Hugh Montgomery that has identified a

gene that allows Tibetans to live and work more than two miles above sea level

without getting altitude sickness.

A previous study published 13 May 2010 in Science reported that Tibetans are genetically adapted to high altitude. Now, less than a month later, a second study by scientists from China, England, Ireland, and the United States pinpoints a particular site within the human genome - a genetic variant linked to low hemoglobin in the blood - that helps explain how Tibetans cope with low-oxygen conditions.

The study sheds light on how Tibetans, who have lived at extreme elevation for more than 10,000 years, have evolved to differ from their low-altitude ancestors.

People who live

or travel at high altitude respond to the lack of oxygen by making more

hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying component of human blood.

But too much hemoglobin can be a bad thing. Excessive hemoglobin is the hallmark of chronic mountain sickness, an overreaction to altitude characterised by thick and viscous blood. Tibetans maintain relatively low hemoglobin at high altitude, a trait that makes them less susceptible to the disease than other populations.

"Many patients, young and old, are affected by low oxygen levels in their blood -perhaps from lung disease, or heart problems. Some cope much better than others," said co-author Professor Hugh Montgomery (UCL Clinical Physiology). "Studies like this are the start in helping us to understand why, and to develop new treatments."

To pinpoint the genetic variants underlying Tibetans' relatively low hemoglobin levels, the researchers collected blood samples from nearly 200 Tibetan villagers living in three regions high in the Himalayas. When they compared the Tibetans' DNA with their lowland counterparts in China, their results pointed to the same culprit - a gene on chromosome 2, called EPAS1, involved in red blood cell production and hemoglobin concentration in the blood.

While all humans have the EPAS1 gene, Tibetans carry a special version of the gene. Over evolutionary time individuals who inherited this variant were better able to survive and passed it on to their children, until eventually it became more common in the population as a whole.

Researchers are

still trying to understand how Tibetans get enough oxygen to their tissues

despite low levels of oxygen in the air and bloodstream. Until then, the

genetic clues uncovered so far are unlikely to be the end of the story.

For those who live closer to sea level, the findings may one day help predict who is at greatest risk for altitude sickness.

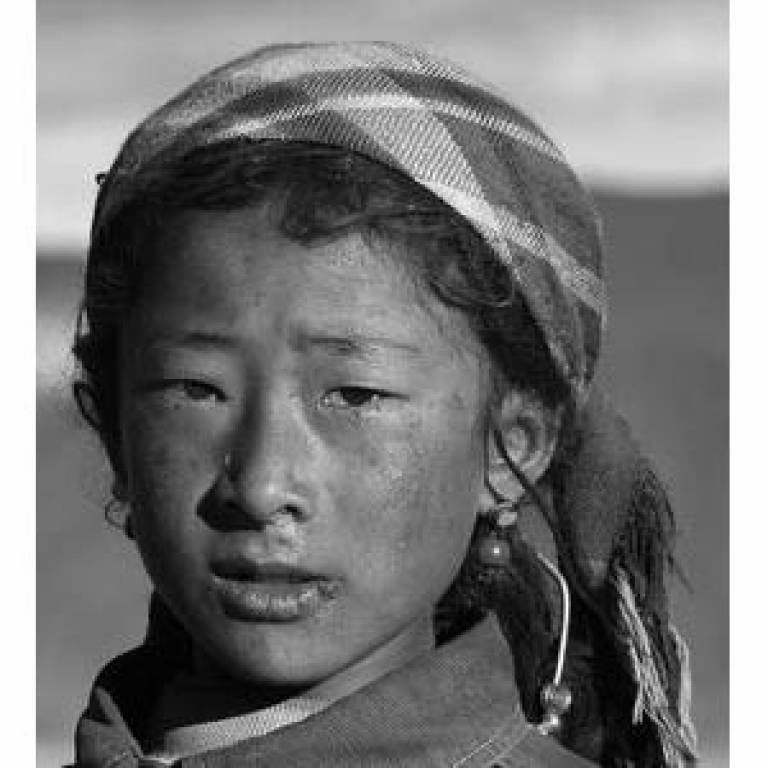

Image: Tibetan Nomad by Michel@, Flickr. Some rights reserved

Related news

UCL-led project lets Genie out of bottle

Mountaineers measure lowest human blood oxygen levels on record

Close

Close