Obama's inaugural address vs past presidents'

21 January 2009

ucl.ac.uk/history/about_us/academic_staff/dr_adam" target="_self">Dr Adam I P Smith, Senior Lecturer at UCL History, analyses Barack Obama's first speech as President of the United States in comparison with those of his predecessors.

ucl.ac.uk/history/about_us/academic_staff/dr_adam" target="_self">Dr Adam I P Smith, Senior Lecturer at UCL History, analyses Barack Obama's first speech as President of the United States in comparison with those of his predecessors.

Presidential inaugural addresses not only speak to the political moment in which they are given; they are also a genre in themselves with a grandiose, almost quasi-religious status that sets them apart from all other political speeches.

Like Fourth of July orations in the early years of the Republic, inaugural addresses have traditionally served as a kind of secular sermon, reminding the faithful of their duties, acknowledging sin and calling for renewal. At their best, past inaugurals have helped to shape the popular image of a presidency, even to define an era: think of John F. Kennedy's "ask not what your country can do for you" or Franklin Roosevelt's "the only thing we have to fear is [dramatic pause] fear itself." How did Obama's speech rate in comparison with these great pieces of oratory from the past?

At his best, the new president certainly stands comparison with any of the great orators who have occupied the White House before him, but on this occasion I sensed that he was pulling some of his rhetorical punches. There were purple passages to be sure, and some of the familiar Obama rhetorical devices (such as the repetition of "on this day") were there, but he did not quite reach the poetic heights that he struck in some of his campaign speeches or in his election night address.

Even so, the echoes of past inaugurals could be heard in almost every line. Like Thomas Jefferson, the first president to take office after a bitterly contested election, Obama spoke the language of unity, promising to transcend partisanship, or, as he put it, the "petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn out dogmas, that for too long have strangled our politics." Like Lincoln, who spoke of "the mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land," Obama heard the "fallen heroes of Arlington whisper through the ages." Like Ronald Reagan, he spoke the language of renewal (or "remaking" as Obama put it) and of the strength of America resting in the faith and determination of the people. And while no post-Cold War president could plausibly compete with Kennedy's appeal to the citizens of the world to ask not what America could do for them but what together they could do for the freedom of man, there was, nevertheless, a definite Kennedy-esque quality to Obama's appeal to those watching from beyond America's borders. His pledge "to the people of poor nations" to "work alongside you to make your farms flourish" echoed Kennedy's words in 1961: "to those people in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves."

Ultimately, Obama's greatest political challenge is a domestic one, and so it was probably not surprising that the inaugural address of the past on which he drew most inspiration appears to have been Roosevelt's in 1933. The central theme was the same: the nation "calls for action" - a phrase that both men used. Both emphasised that Americans' capacities were undiminished. "Our distress comes from no failure of substance," said FDR, while Obama insisted that "our workers are no less productive than when this crisis began." Early in his speech, Obama blamed the weakening of the economy on the "greed and irresponsibility of some" which, if it did not quite have the biblical passion of FDR's condemnation of the "practices of the unscrupulous money changers," at least nodded in that direction. And if the new president struck a more down-beat tone than he often has in the past, the reason, no doubt, was that, like FDR, he wanted to remind his fellow citizens that the road ahead would be a tough one.

Such echoes are to be expected. They are as familiar, yet as essential to the ritual, as the flags and the singing of Sweet Land of Liberty. But was there any one phrase which will become indelibly associated with the age of Obama? My initial thought is that the line that is most likely to be repeated most often in the coming days is his stinging riposte to the foreign policy of the outgoing president: "we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals."

I suspect, though, that in the long run, this speech will be remembered not for one or two beautifully turned phrases, but for something rather sterner. American political rhetoric has historically been caught between two competing impulses: to celebrate the "city on a hill" as a place with a Providential mission to redeem mankind, or to see it as an ideal to be continually sought, probably never to be perfectly attained. Many presidents have confidently articulated the first of these interpretations of the meaning of America. Few have so emphatically identified themselves with the second as President Obama.

The most striking thing about his inaugural address, in my opinion, was his willingness, like a Puritan preacher invoking the prophet Jeremiah, to make Americans confront the idea that somehow they were all culpable, they had all strayed from the path. It may be that a good guide to the Obama administration will be his formidable assertion that "our collective failure to make hard choices" has contributed to America's problems. FDR did not say this in 1933. Reagan certainly didn't in 1981. In this most fundamental respect, Obama's speech most recalled Lincoln's remarkable second inaugural address in which he acknowledged that the North was as culpable as the South for the sin of slavery and speculated that God gives to "both North and South this terrible war" as retribution for their collective guilt. Obama's closing line -- "let it be said by our children's children that when we were tested we refused to let this journey end" - seems to reaffirm his very Lincolnian idea of America as a work in progress.

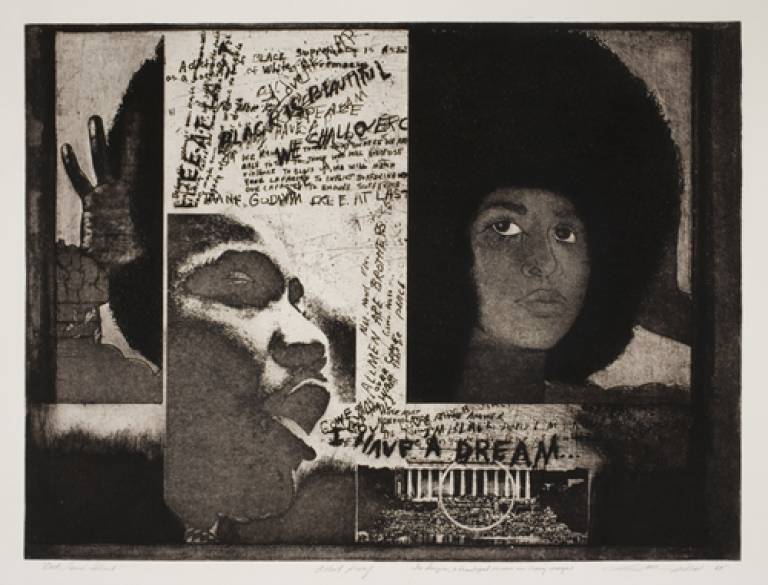

Image: 'Out-Loud Silent', photo-etching and aquatint by Lev T. Mills (UCL Slade School of Fine Art 1970-72). Presented to UCL Art Collections by Bartolomeu dos Santos, 1997

UCL Context

Dr Smith's book 'The American Civil War' was published by Palgrave in 2007. Dr Smith's area of research is the history of the United States, specialising in the issues of political culture, nationalism and political mobilisation.

Professor Philippe Sands (UCL Laws) will discuss the challenges and opportunities facing the 44th President of the United States, in foreign affairs and beyond, in his Lunch Hour Lecture on 27 January.

The UCL Commonwealth Fund Lecture on 19 February will examine Lincoln's lasting political legacy.

Close

Close