Oldest case of leprosy found in 1st century tomb

16 December 2009

Links:

plosone.org/home.action">PLoS One

plosone.org/home.action">PLoS One

Analysis of human remains buried in the 1st century 'Tomb of the Shroud' in Jerusalem has revealed evidence of ancient leprosy and tuberculosis.

The new research, involving UCL researchers, is published in the journal PLoS One today.

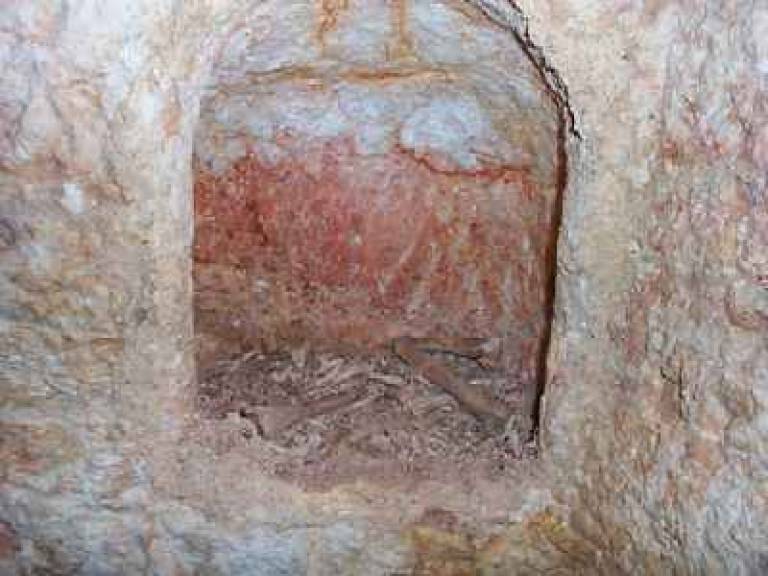

This is the first time that a 1st century tomb from Jerusalem has been investigated by molecular methods. Analysis of the ancient DNA showed both leprosy (Hansen's disease) and tuberculosis (TB) present in male remains found in a small-sealed off chamber within the tomb. This finding is the oldest known case of leprosy with confirmed dates and molecular evidence.

The 'Tomb of the Shroud' dates from the time of Jesus and was discovered in Jerusalem in 2000 by an international archaeological team led by Shimon Gibson, Boaz Zissu and James Tabor. The rock-hewn burial cave, one of 70 or more in the area, belongs to a cemetery known as Akeldama or 'Field of Blood', as described in the Bible (Matthew 27:3-8; Acts 1:19). The cemetery is located in the lower Hinnom Valley in Jerusalem. Although the tomb had been illegally entered and looted, the robbers had not found all the burial chambers, meaning those that were untouched could be studied in detail.

Last author of the paper Dr Helen Donoghue, UCL Centre for Infectious Diseases & International Health, was one of the international team that discovered the evidence of tuberculosis and leprosy. The team was led by Charles Greenblatt at the Kuvin Centre for Tropical and Infectious Disease at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, and also included Carney Matheson at the paleo-DNA Laboratory at Lakehead University in Canada.

Dr Donoghue commented: "The evidence of tuberculosis and leprosy significantly aids our understanding of the historical geographical distribution of these diseases and adds a new dimension to the archaeological exploration of disease in antiquity. As well as evidence of leprosy and TB in the male remains, the analysis also revealed that some of the other individuals in the multi-chambered tomb showed signs of tuberculosis and ancient human DNA was detected to piece together the family relationships.

Co-author Professor Mark Spigelman, Visiting Professor at the UCL Centre for Infectious Diseases & International Health and the Kuvin Centre for Tropical and Infectious Disease, Hebrew University, added: "When this tomb was discovered, one small chamber was still sealed and housed the remains of a man and the remnants of a burial shroud - the only one that has survived from the 1st century in Jerusalem.

"The normal practice at that time was for the bones to be collected and re-buried in an ossuary, so the fact that these remains were separated off from the others in a sealed chamber prompted questions about why. The presence of leprosy explains this arrangement and the data we have extracted helps us to understand more about these ancient diseases."

Image: Human remains in the Tomb of the Shroud (Copyright: Shimon Gibson)

UCL Context

Close

Close