Q&A: Nikita Lalwani, UCL writer-in-residence

20 June 2008

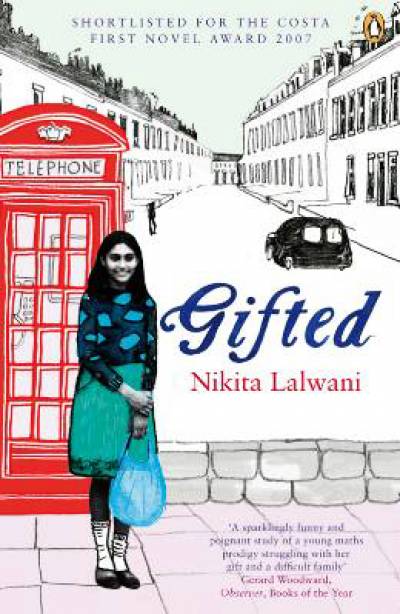

Nikita Lalwani's debut novel

penguinrandomhouse.com/books/97275/gifted-by-nikita-lalwani/9780812977943/" target="_self">'Gifted' was a painful yet heartwarming exploration of a British-Indian prodigy's premature passage to university and maturity. It led to a Man Booker Prize longlisting, a Costa First Novel Award shortlisting and an invitation to be writer-in-residence at UCL English.

penguinrandomhouse.com/books/97275/gifted-by-nikita-lalwani/9780812977943/" target="_self">'Gifted' was a painful yet heartwarming exploration of a British-Indian prodigy's premature passage to university and maturity. It led to a Man Booker Prize longlisting, a Costa First Novel Award shortlisting and an invitation to be writer-in-residence at UCL English.

UCL is mentioned in first few pages of 'Gifted'. How did you come to be writer-in-residence here?

That is so interesting. I hadn't really thought of the two together but of course you are right. It's in the novel because it is representative of a high-class place - incontrovertible, a marker of academic achievement. I ended up here because Matt Beaumont [lecturer at UCL English] contacted me after reading 'Gifted'.

How did your expectations of UCL compare with the reality?

I think the reality was much better. I am a bit wary of formalised arrangements and bureaucracy, intellectual hierarchies, or grading when it comes to writing, and the post turned out to be really what it suggests - a writer in residence. It was an active role: dialogue, workshops and writing with students who came along out of choice, in an extra-curricular capacity. I thought that was mighty refreshing.

The students in 'Gifted' are earnest, hardworking under pressure. How do they compare with UCL students?

I haven't encountered students in the purist sense during my time here; people have come along as writers who want to share work, or be cajoled into writing, rather than as students. It is a bit like being inside the visible framework of an academic institution, but without all the meat and stuffing of it in our sessions ie research, percentages, etc. Instead I think I've been encouraging slightly obscene emotional revelation, the shaking off of politeness. When it worked, there was a lot of cracking dialogue.

What was the highlight of your time here?

I think it was the day I asked everyone to write down a secret and put it in a box for someone else to pick out and write about. One or two of the secrets were really honest and led to something quite moving, writing-wise. Gratuitous emotionalism again, you see.

Has the experience affected how you write?

Not yet visibly affected, but drops of it must be lurking under the skin, surely.

What was your own experience of academia?

I went to Oxford when I was 18, to study medicine, and was asked to leave after my first year for not really doing enough work to get by. I think I was railing against something quite so factual and rational. A lot of undergraduate medicine is about memory rather than ideas and I think I found it hard to devote myself to something so devoid of subtext. I went for it because I believed it was a noble trade, though. I then went to Bristol to study English Literature, and finally to Cardiff for a Broadcast Journalism postgraduate course.

What inspired your first novel - the decision to write and the subject matter?

I suppose I was inspired to become a writer by reading novels as a child. You become a fan of a particular kind of fictional world and that frame of communication; mine was the novel before I came to watching films and other media. Regarding 'Gifted', I'd been interested in the notion of 'genius', its mystification by society - the passive or active nature of it when relating to children - for a long time. Add to that the fact that, like most people, I went through adolescence, and I think about those years quite a bit. Those are the bare bones.

How would you class 'Gifted' in terms of genre?

I'd say it's about 41 per cent autobiographical. It is a coming-of-age novel that has Bildungsroman elements, with the maths patterning and particular cultural backdrop. It has a campus element in part three but the protagonist is never fully immersed in that life; it is more about academia in family life I'd say - isolation, solitude - rather than the bawdy comings and goings in a traditional campus novel.

Do you see yourself as a British-Indian writer?

It is difficult to classify yourself with an outsider eye. This question often leads to dirtier questions about 'authenticity'. I suppose I always think it's for the reader to decide on this one; only the gaze can place it. I'd say my literary influences are Don DeLillo, Milan Kundera, Salman Rushdie, Siri Hustvedt, Chekhov, DH Lawrence, Anna Akhmatova.

In an interview in 'The Guardian' last month, you said you are in the thick of your second novel. What can you tell us about it?

Not much other than I am hoping to create a 'sticky moral universe'. That sounds impressive, doesn't it?

How has being longlisted for the Booker affected you, and your writing?

I've always followed the Booker; it was eerie and thrilling to be on that list. I think they made a very definite statement last year drawing up a list of little-known writers, and I was lucky to be in it. Awards are products of their time, branding and particular cultural climate, so I don't take the award part too seriously, but having

been published as an unknown, it does feel like something like a luxury to be visible and read at all, so that has been the main outcome.

Image courtesy of Bartlomiej Kwasek

Interview by Lara Carim, UCL Communications

**********************

Extract from 'Gifted' by Nikita Lalwani, published by Penguin

'Have you heard of a place called Mensa?' said Mrs Gold.

Mahesh felt exasperated. He had seen all the same adverts as her. The ads for this place she named with such careful tedium, as seen though she was rolling a diamond round her mouth. 'Mensa'. He'd seen their childish IQ tests, fooled around with filling them out in the Sunday papers. He knew what Mensa was, for goodness' sake. What did she take him for? And why was she so surprised that he and his daughter could string numbers together with reasonable panache? They were hardly shopkeepers.

He was 'peed off', as they said here: irritated. He tried to think of more slang, enjoying the taste of righteousness, dousing each word with it. He was 'hacked off', 'cheesed off', 'not pleased'. What did she think? That he was some third-rate charlatan, preening his feathers under the banner of academia? He felt a rumble in his stomach as the bhajis fermented, rising as though to validate his sense of pique. Oddly, the sensation cheered him. He felt like making a grand statement to this woman, one that Rumi would witness, about how it was possible through strength and discipline to create your own destiny using the power of thought: through marks, percentages, papers, exams, numbers that had added up, in his case, to a big sum in small hands - a scholarship across the ocean.

He surveyed Mrs Gold's darting eyes. She was watching his wife as she sipped her tea. Shreene was returning her gaze, looking round the room at intervals. What preconceptions did she bring with her - this queer-spoken woman with her little smiles and polite contradictions? He was not going to make a grand statement. It would only confuse things. But, if he could, he would tell her everything. He'd tell her he'd got into all their universities - all the bloody jewels they treasured so exclusively in this country: that he had been offered a place at their Cambridge and their UCL. He had ended up in Cardiff because they had offered the cash - several thousand pounds of it, a sum no one could deny for its totality. Full fees. They had wanted him here, a foreigner with no more than five pounds in his pocket and a slip of a wife, bare-toed and shivering. That was how he had got off the plane with Shreene in 1972, newly wed and aware, dignified by the patronage of their red-brick institutions, sure as a compass, leading the way for them both.

He had not been among the thirty thousand Asians haemorrhaging out of the ugly scar in Uganda's belly that same year, seeping into the dark spaces of Britain, afloat in the soiled bathwater of Amin's shake-up: the crawling masses who had fallen into the pockets of Leicester and Wembley. He was not going to be dissolved into the rivers of blood, among Enoch Powell's armies of bacteria, defecating in people's nightmares on the landscape of their precious country.

He was Dr Mahesh Vasi, PhD, a man who had begun his maths career repeating times tables under a large tree in Patiala with fifteen schoolmates, embossed with dust and driven by the pure heat of numbers. Now he was here, working just over an hour's commute away, speaking to a room of one hundred students each week, employed in name by the University of Swansea, sub-set of the University of Wales itself. What about that then?

Mahesh cleared his throat and considered how to proceed. He uncrossed, then re-crossed his legs with an air of what he hoped was leisurely contemplation. He still had to learn how to relax, uncoil the ritual desire to please. It was a shameful habit, nothing else, he told himself.

Shreene offered Mrs Gold the plate of snacks. The vegetables shone through the batter with glistening heat: dark purple aubergine skins and green courgettes, pushing their thick curves through the fried covering. 'Please - have one,' she said, smiling and pressing a paper napkin into the teacher's hand. 'Do you like spicy food?'

Mahesh took the opportunity to interject. 'I know Mensa very well, Mrs Gold. I'm happy to go there with Rumika and see what it is like.'

|

UCL Context Several departments at UCL host eminent writers-in-residence to encourage creativity in writing and translating, and a different perspective on literary study. Related stories Kader Abdolah: In the kitchen of the writer Writers-in-residence: a novel role |

Close

Close